Even Before Modi, India Was No Bastion of Free Expression

The world’s biggest democracy has a long history of curtailing speech

Last month, when the G7 heads of government signed a joint statement affirming respect for “freedom of expression” and other principles of open societies, Narendra Modi—the prime minister of India, one of four guest countries—was also a signatory. That provoked a domestic backlash in India. Opposition leaders slammed Modi for saying one thing and doing another, pointing out that India today is not a place with respect for freedom of speech.

In doing so, however, Modi’s critics invited consideration of an awkward question: Has India ever really been a place with respect for freedom of speech?

India is the world’s biggest democracy, but its health as a liberal democracy—one in which the government protects freedoms and the rule of law—has been a subject of much worry among international observers in the seven years since Modi came to power. And this is understandable: He has pushed back on press freedoms, locked up opposition politicians, and abused terrorism charges for political ends.

It is worth remembering, though, that while India has become increasingly illiberal under Modi, it did not have a spotless history of protecting free expression before he came to power. Indeed, many of the loudest critics of Modi and his party—Modi leads the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)—come from another party that hardly has a sterling record of protecting free expression.

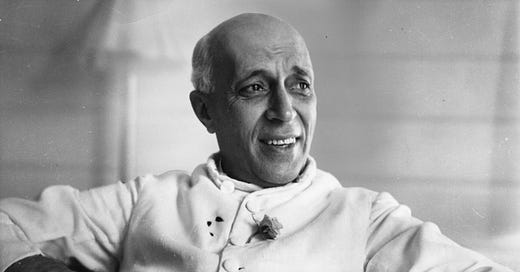

Look back to the formation of the Indian state. The country’s constitution was ratified in 1949 and took effect in 1950. By the next year, Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru’s government responded to recent court rulings by ramming through an amendment that altered the constitution in several key ways. One of these changes permitted the government to restrict freedom of speech in significant ways, a striking contrast to the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution (as Nehru’s critics observed at the time). (The story of this amendment’s creation is the subject of historian Tripurdaman Singh’s 2020 book Sixteen Stormy Days.)

The genie was out of the bottle. With the passage of this amendment, Nehru and his party, the Indian National Congress, had established not just a precedent but a principle: Where the people’s freedoms impeded government policy, the people were wrong and would be overruled.

His daughter would take this to new lows. Prime Minister Indira Gandhi was swept into power in 1967 and re-elected with an expanded Indian National Congress majority in 1971. But the candidate whom she defeated in her home constituency in 1971 accused her of electoral illegalities, and a court ruled in his favor in 1975—ordering Gandhi removed from her parliamentary seat, which would also have ended her premiership. She refused to go, and within days suspended both the liberal and the democracy parts of India’s liberal democracy.

During what was called the “Emergency,” all decisions were made by Gandhi and her son, Sanjay Gandhi, who became famous for beautifying Delhi by displacing and killing the homeless and poor and starting compulsory sterilization programs. Dozens of opposition leaders were arrested. The government forced foreign correspondents out and withdrew accreditation from domestic reporters. Some news outlets saw electricity to their offices cut by government order and until the next election; the chilling effect meant that most journalism during this period amounted to cheerleading for the government. People who did not support the government’s actions, no matter what they were, were blacklisted on government radio and television. This included Bollywood luminaries, such as Kishore Kumar, who went from a ubiquitous presence on soundtracks to being banned from government radio, out of a desire to not act as a puppet for regime.

After about twenty months, the Emergency was lifted and Indira held elections—and this time, her party was defeated and she lost her own seat (to the same candidate who had challenged her in 1971). But because the coalition that won had only one thing holding it together—a shared dislike of Gandhi and her reign—it was too unstable to govern for long. Within a few years, Gandhi was back in parliament and back in power as prime minister.

After Indira Gandhi’s assassination in 1984, her other son, Rajiv Gandhi, was made prime minister, serving until 1989. Though his tenure was most famous for the religious riots he engendered shortly after his mother’s death, he was also the prime minister who in 1988 banned Salman Rushdie’s Satanic Verses. India was the first country to issue such a ban; the attention (and subsequent bans) from much of the Muslim world came after this.

Today, it is the party of Nehru, Indira, and Rajiv—the Indian National Congress party—that is arguing for the importance of freedom of speech. In a way, this was bound to happen. The Nehru-Gandhi family has been associated with the Congress party for more than a hundred years—today, Rajiv’s son and widow lead the party and it still in very real ways is a family enterprise. However, this has real costs—the party is electorally uncompetitive but because it insists on defending its worst leaders, it is unable to effectively mount a real defense for freedom of speech and freedom of expression more broadly.

India deserves leaders who mean it when they talk about freedom of speech. As long as the Congress party is dedicated to the family that ran roughshod over that principle, they won’t be able to be those leaders.