In 2020, the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. included so-called “whiteness” traits in its “Talking About Race” online portal. It created a kerfuffle. The National Museum of African American History and Culture advised that:

White dominant culture, or whiteness, refers to the ways white people and their traditions, attitudes, and ways of life have been normalized over time and are now considered standard practices in the United States. And since white people still hold most of the institutional power in America, we have all internalized some aspects of white culture—including people of color.

Among the traits that were considered vestiges of whiteness were the belief that “hard work is the key to success,” and that “objective, linear thinking” is superior to other kinds. Whiteness also apparently encompassed “planning for the future” and “respecting authority.”

When this created a stir, the museum (which is fantastic, by the way) removed the online post and apologized. “Education is core to our mission,” the museum statement said. “We thank you for helping us to be better.”

That isn’t the way things normally roll here in 21st century America. No, our more typical response is spittle-flecked outrage, misleading accounts, and imprecations. Anger and outrage sell, no doubt. And while the news has always had a negative tilt (“If it bleeds, it leads”) the omnipresence of news and commentary on our phones and laptops along with the competitive pressure of click-based journalism has created a bottomless appetite for outrage. A polity that is constantly inflamed is not well equipped to handle reality.

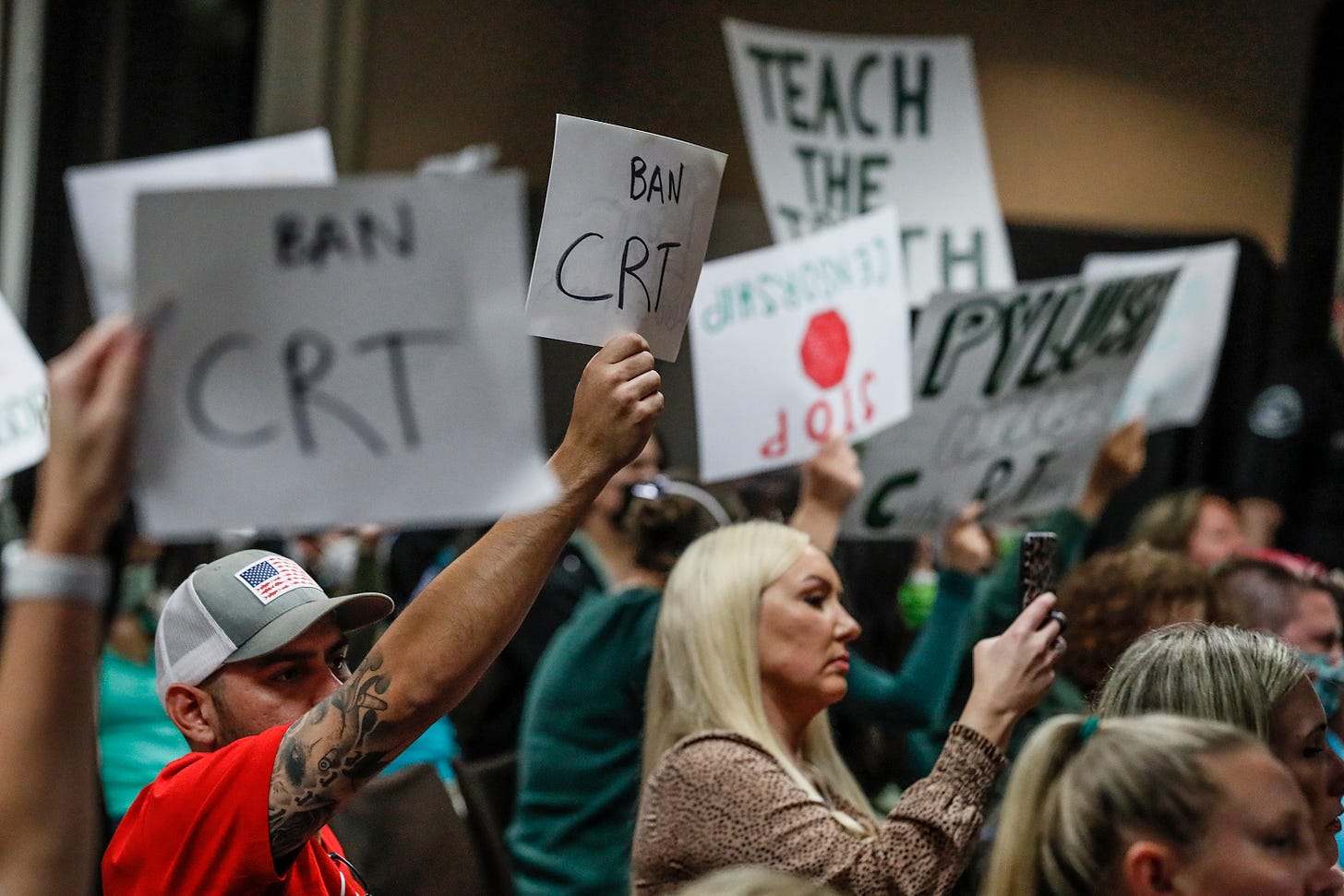

As the Smithsonian example illustrates, there are problems with the critical race theory (CRT) approach. In fact, in my view, it represents a dangerous retreat from the core American values of tolerance, pluralism, and color-blindness. And yes, it is also the case that some Republicans and conservatives are making bad-faith arguments and blowing on the embers of racism. So let’s attempt a little tidying up.

The laws some Republican-dominated states are passing to curtail CRT and its progeny are bad ideas for many reasons. But the depictions of those laws in big outlets like the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal, and the Washington Post are frequently wrong or incomplete. A recent CNN report about Florida’s new law that would prohibit teaching methods that make people "feel discomfort, guilt, anguish, or any other form of psychological distress on account of his or her race, color, sex, or national origin" mangles the facts. The law, CNN claims, is a response to critical race theory, which the network defines as “a concept that seeks to understand and address inequality and racism in the US. The term also has become politicized and been attacked by its critics as a Marxist ideology that's a threat to the American way of life.”

Not quite, though CNN is hardly alone in describing CRT in such an anodyne fashion. Paul Krugman argues that most people don’t know what CRT is (which is true), but goes off the deep end claiming that Republican “denunciations of C.R.T. are basically a cover for a much bigger agenda: an attempt to stop schools from teaching anything that makes right-wingers uncomfortable.” One news outlet suggested that anti-CRT bills “may make it even harder to discuss African American history,” and it is common to see anti-CRT bills described as “efforts to restrict what teachers can say about race, racism and American history in the classroom.”

If you were judging by much of the mainstream press coverage, you would think that CRT is just a movement to ensure that the history of slavery, racism, and Jim Crow is not neglected in America’s classrooms. But 1) large percentages of both Republicans and Democrats favor teaching those things, and 2) that’s not what CRT is.

In their book Critical Race Theory: An Introduction, Richard Delgado and Jean Stefancic state forthrightly that “Critical race theory questions the very foundations of the liberal order, including equality theory, legal reasoning, Enlightenment rationalism, and neutral principles of constitutional law.” Robin DiAngelo, author of White Fragility, rejects the notion that racism is a character flaw in some individuals, declaring instead that “White identity is inherently racist.” That marks a dramatic departure from the traditional understanding of racism.

Critical race theory adherents favor teaching techniques that most Americans believe violate our commitment to colorblindness, such as “affinity groups” wherein people are segregated by race to discuss certain issues. In Massachusetts, the Wellesley public schools hosted a “Healing Space for Asian and Asian American students and others in the BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, People of Color) community.” An official email explained that, “This is a safe space for our Asian/Asian American and Students of Color, *not* for students who identify only as White.”

In Virginia’s Loudoun County, teacher training materials encouraged educators to reject “color blindness” and to “address their whiteness (white privilege).” Each teacher was exhorted to become a “culturally competent professional who acknowledges and is aware of his or her own racist, sexist, heterosexist or other detrimental attitudes, beliefs, behaviors, and feelings.” The training strayed into racial essentialism like this: “To the African, the entire universe is vitalistic as opposed to mechanistic. . . . This precept suggests that African Americans have a psychological affinity for stimulus change, often exhibit an increased behavioral vibrancy and have a rich and sometimes spontaneous movement repertoire.”

Democrats often object that CRT is “not taught in K-12 schools,” which is evasive. It’s true that third graders are not being assigned the works of Kimberly Crenshaw or Ibram X. Kendi, but affinity groups, “anti-racism” (in the sense of rejecting the ideal of color blindness), and other CRT-adjacent ideas are making their way into classrooms. New York City has spent millions on training materials that disdain “worship of the written word,” “individualism,” and “objectivity” as aspects of “white-supremacy culture.”

As is their wont, some Republicans have made things even worse. A conservative group is suing a school district in Tennessee because its second grade curriculum included a “Civil Rights Heroes” module that included a picture book about Ruby Bridges. The parents claim that the unit violates Tennessee’s new anti-CRT law and contains material that is “Anti-American, Anti-White, and Anti-Mexican [sic].”

Other bad-faith actors like Christopher Rufo are attempting to taint many views they disagree with as CRT, which Rufo describes as “the perfect villain.”

It’s so easy—and remunerative—for progressives to characterize opposition to CRT as straight-up racism, and for conservatives to reach for heavy-handed, overbroad laws to restrict teaching they resent. But it is possible to oppose CRT for non-racist reasons, in fact for pro-national unity reasons, and even if Republicans are not making the case well or at all, it still needs to be made.

Large majorities of both Republicans and Democrats favor teaching about slavery, racism, and other sins of American history. Eighty-eight percent of Democrats and 64 percent of Republicans favor teaching that slavery was the cause of the Civil War. Ninety percent of Democrats and 83 percent of Republicans believe textbooks should say that many Founding Fathers owned slaves. Nearly identical percentages of Democrats (87) and Republicans (85) say textbooks should include the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II and slightly higher percentages want children to learn about the theft of Native American land.

That is not the picture of a nation (or even one party) that is refusing to grapple with the history of racism. Where you do get partisan divergence is on whether schools should teach the concept of “white privilege.” Seventy-one percent of Democrats say yes, but only 22 percent of Republicans agree.

The Republicans are right on this. This is not to say that white privilege doesn’t exist, but teaching it in schools is nearly certain to have the opposite effect of what proponents hope and opponents fear. In response to Republican anti-CRT laws, some Democrats are sneering about Republican snowflakes. But what’s the likely outcome of lessons that encourage kids to think in terms of race all the time? What’s the likely result of telling white students, with their varying incomes, backgrounds, and life circumstances, that they are the bearers of “white privilege?” I don’t think most of them are going to feel guilty. They’re going to get angry. They’re going to feel alienated from their Black classmates. They’re going to reflect on all the ways life has handed them the short straw and demand to know how they can be called “privileged.” Teaching like that sets up an inter-group victim sweepstakes in which everyone loses.

The goal of teaching about slavery, racism, and other sins is to tell the truth. For the same reason, schools should teach about the admirable progress we’ve made in moving toward a more just, multiethnic society. If we’re hoping to elicit the right feelings from students—and we should—then the feelings we’re after are sympathy, understanding, and solidarity, not guilt.