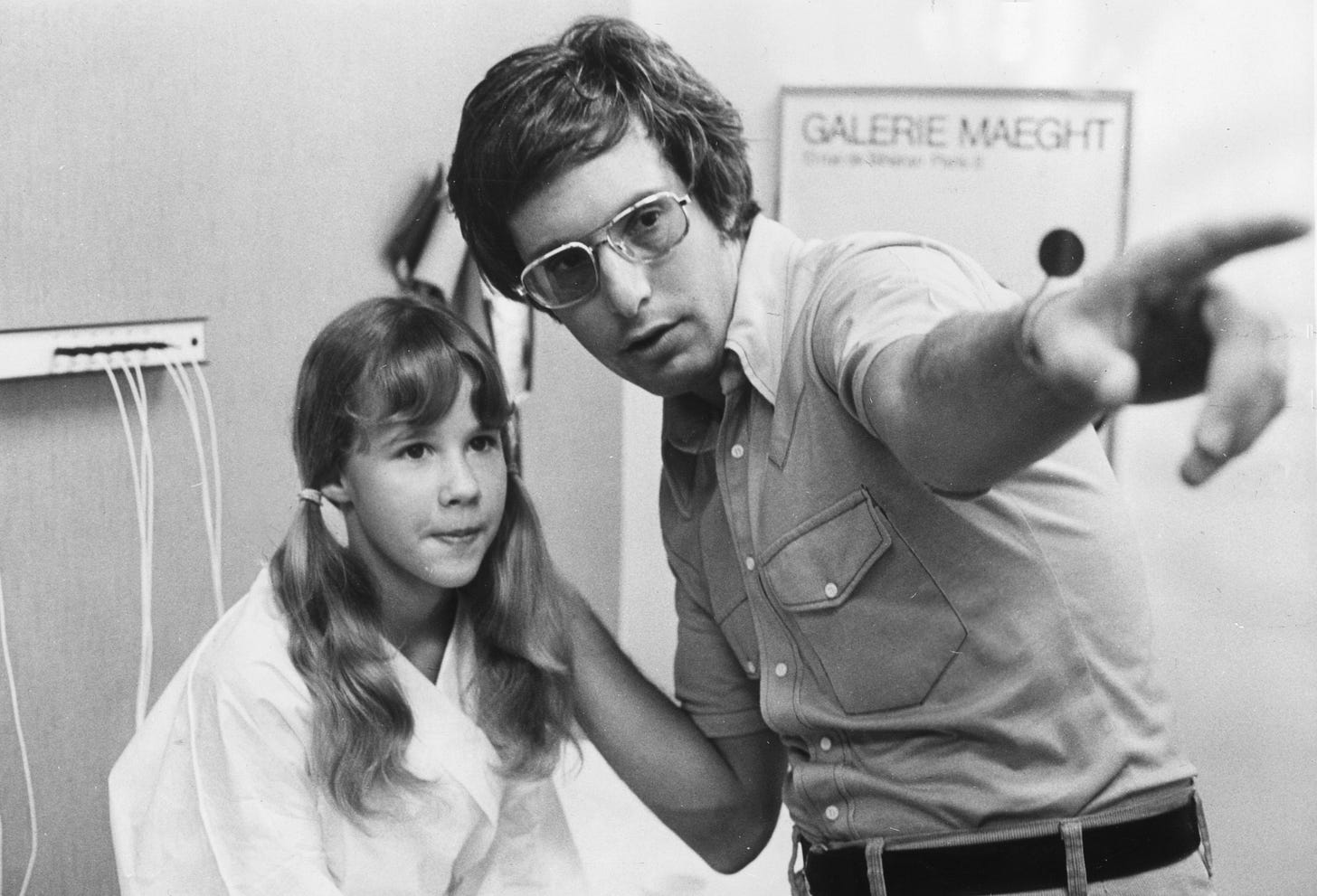

William Friedkin, 1935–2023

The career ups and downs of the director of ‘The French Connection’—plus, what people *still* get wrong about ‘The Exorcist.’

FILM DIRECTOR WILLIAM FRIEDKIN, who died on Monday at age 87, began his career with movies that were somewhat at odds with those he would eventually become famous for. He started with a handful of social documentaries, including, most famously, The People vs. Paul Crump (1962), about a black man on death row for killing a security guard during a robbery. As soon as he was able to break into narrative features, he did, with Good Times (1967), a sort of sketch comedy movie starring Sonny Bono and Cher. That movie would have been a curiosity no matter who directed it; it became odder still as Friedkin’s career progressed.

Friedkin’s output in the late 1960s showed a filmmaker struggling to find his place, his point of view, and his style. As it happens, The Birthday Party (1968), his next film after Good Times, is, to me (and perhaps only to me) his first masterpiece. Based on a play by Harold Pinter and starring, among others, Robert Shaw and Patrick Magee, Friedkin brought to The Birthday Party strikingly eerie visuals—some subtle, others almost shrieking as the story and characters get more and more out of control—as if he’d been making such films for ages. His style, this kind of icy brutality, had apparently just been sitting in his head, waiting to get out. Unfortunately, that same year his third feature, The Night They Raided Minsky’s was released, and that one, according to Friedkin, was more of a Norman Lear project than anything. “I brought what I could to the picture, but I was the director in name only,” Friedkin wrote in his memoir, where he also lamented that the film was so disastrous he worried about his career ending before it had really begun.

But after that came what must be considered the peak of Friedkin’s career. It began with The Boys in the Band (1970), based on Mart Crowley’s play about a group of gay friends gathering for a birthday party. Though it wasn’t a financial success, the film did well with critics, and in any case, became a landmark film in the depiction of homosexuality on film.

Then came The French Connection (1971), the film that, my own personal preferences aside, must be regarded as the central picture of Friedkin’s career. Winner of several Academy Awards, including Best Picture and Best Director, this grim, and sometimes grimly funny, cop movie looms large over the American cinema of the 1970s, unapologetically nasty and mean (one gets the sense that Gene Hackman’s “hero,” Popeye Doyle, would be fine indirectly causing the deaths of any number of civilians if it meant he were able to nab his culprit), while still managing to be a massive hit. The French Connection was fortunate to be released in perhaps the only decade when the public would welcome it with open arms.

William Friedkin had a reputation for fiddling with, well, not so much his films as a whole, but with The French Connection specifically. This has caused some uproar among cinephiles for years. The first time this happened was in 2009, when a new Blu-ray of the film was released. As it turned out, Friedkin had gone back and changed the color timing in a way that, to many, rendered The French Connection visually ugly, close to unwatchable. The protests were such that Friedkin and cinematographer Owen Roizman, whom Friedkin had not previously consulted, got together to restore the film again, in a way more amenable to all parties. More recently—just two months ago, in fact—it was discovered that the version of The French Connection that can be found digitally in the United States cuts out a particularly charged racial slur. The edit that now exists is more jarring than anything in that color-timing fiasco, and, as critic Glenn Kenny laid out in this piece after investigating the matter, evidence points to this edit being the decision of Friedkin himself. But nobody knew for sure, and the pressure to explain was now on Friedkin. He never bothered to do so, for reasons that should now be apparent, and I suppose we’ll never know what happened. Anyway, I’m holding on to my correctly color-timed and unedited Blu-ray, thank you very much.

REGARDLESS OF ANY OF THAT, the stage was now set for the two Friedkin movies that I consider his best. One shot his star higher than even The French Connection had; the other just about ruined him. The first, of course, is The Exorcist (1973). This, to me, is an incredible achievement, the best horror film ever made, produced with a level of artistry and moral seriousness that the genre would spend most of the next couple of decades fighting against. Summarizing the plot should be unnecessary at this point, but I recently had reason to consider the film again when I saw comedian and horror fan Dana Gould offer up, on a Shudder documentary, a completely and provably incorrect reading of The Exorcist’s philosophy. He said that the film is about “how God can’t save you.” This is of course the opposite of what the movie is about, and it’s frustrating to see such a sincere work of faith, on the parts of both writer William Peter Blatty and Friedkin (Friedkin was Jewish, but in his passion for The Exorcist, and his friendship with Blatty, expressed a kind of sympathy with Christianity), so badly misconstrued. Gould’s reading didn’t originate with him—it’s been around as long as the movie has—and it’s something that deeply bothered both Blatty and Friedkin over the years, leading to the misbegotten “The Version You’ve Never Seen” cut of the film in 2000.

Next was Sorcerer (1977), a loose remake of Henri-Georges Clouzot’s The Wages of Fear (1953), about a small group of shady loners who are hired to drive trucks full of leaking dynamite over the treacherous hills and bridges surrounding a small South American village. To me, Sorcerer outshines the Clouzot film by feeling more filthily real, the gasp-inducing suspense rarely underlined by a music score, the tension interminable while star Roy Scheider seems to age several years in two hours. Parts of Sorcerer, especially near the end, appear to have been shot on the moon, an empty and unsafe place, somewhere humans shouldn’t be. The film is gorgeously hopeless, a magnificent thriller that makes it feel like your limbs are slathered in mud, your face encrusted with dirt. It quickly died in theaters. Part of the reason for this failure, some have said, is due to audiences thinking the title Sorcerer promised another Exorcist. Which just proves that people have been stupid pretty much forever.

The rest of Friedkin’s career is a real rollercoaster of lowlights and highlights. The lowlights include largely forgotten films such as Deal of the Century, The Guardian, and, depending on whom you ask, Jade (I don’t think it’s quite the catastrophe many do). On the positive side of the ledger are a lot of movies that are really interesting and pure Friedkin: To Live and Die in L.A., Rampage, The Hunted, and Cruising. This last film stars Al Pacino as a cop investigating the murders of gay men in New York. This leads him into posing (or is he, etc.) as a gay man who frequents NYC’s BDSM clubs. It’s all suitably shocking, and the gay community was not one bit happy that the film was being made; demonstrations were carried out during filming, with roving bands of protesters making so much noise they drowned out some of the dialogue. I don’t think that Cruising is saying “This is what gay men are like” and in fact the character played by Don Scardino is evidence against that assertion. I think it’s really about Pacino’s homicide detective, and the dark parts of himself that are brought out during the investigation (and I don’t mean the fact that he might be gay).

ALONG WITH BEING A MASTER FILMMAKER with a fascinating, if occasionally cautionary, career (he sure didn’t let past controversies affect his current decisions), Friedkin was known as a real Personality. He was once, by his own admission, an unpleasant man, quick to anger, and insulting to others. Though he appeared to have reformed that side of himself, he was still acerbically opinionated, to the extent that at least two documentaries were made about him in the last few years. One of them is called Friedkin Uncut, and he was one of the few directors for whom the “uncut” warning actually meant something. An offshoot of this is that he clearly never gave a damn what people thought of the movies he made, especially later in life.

He has one movie in the can, The Caine Mutiny Court-Martial, which is going to premiere next month at the Venice Film Festival, but before that his last two films (the last two ever, it seemed at the time) were the astonishing one-two punch of Bug and Killer Joe. Both are based on plays by Tracy Letts, each one is almost equally shocking; Killer Joe was rated NC-17 before being released unrated, and it’s not hard to see why. They’re violent, grimily sexual, unpleasant, and among the best films Friedkin ever made. Bug—about a woman (Ashley Judd) who is, in effect, “infected” by the self-destructive and psychotic paranoia of her boyfriend (Michael Shannon)—is a deeply sad movie. The central characters hurt no one but themselves (well, and one other guy, if that actually happens); the film’s teeth-pulling scene is queasily funny, but also a point of no return. In Killer Joe, however, there is no one to like, save Juno Temple’s Dottie, who nevertheless has been so ruined by her parents (the father played, hilariously, by Thomas Haden Church; the mother is killed off-screen early in the story; the stepmom played by Gina Gershon doesn’t do Dottie any favors, either). Everyone else is scum. If Matthew McConaughey’s terrifying Joe is the worst of the lot, certain events near the end, and some subtle insinuations about other characters, make this just a matter of degrees.

And that was the point of William Friedkin. Whenever he could, he made exactly the movies he wanted to make and damn the critics and the public who didn’t like it. I’m of course cleaning it up a little bit, this being a serious website. Friedkin likely wouldn’t have said “damn.”