1. Catastrophic Fail

We’re going to take a bit of a journey today.

I was reading Charlie Warzel this morning and followed a link to an old essay by Richard Cook titled “How Complex Systems Fail.” Cook is an M.D. who was writing about how docs mess up, and why, and what we can learn about medical failures.

It’s kind of profound.

Here’s the progression in Cook’s essay that interests me most:

Complex systems are intrinsically hazardous systems.

All of the interesting systems (e.g. transportation, healthcare, power generation) are inherently and unavoidably hazardous by the own nature. . . . It is the presence of these hazards that drives the creation of defenses against hazard that characterize these systems.

Complex systems are heavily and successfully defended against failure

The high consequences of failure lead over time to the construction of multiple layers of defense against failure. These defenses include obvious technical components (e.g. backup systems, ‘safety’ features of equipment) and human components (e.g. training, knowledge) but also a variety of organizational, institutional, and regulatory defenses (e.g. policies and procedures, certification, work rules, team training). The effect of these measures is to provide a series of shields that normally divert operations away from accidents. . . .

Complex systems contain changing mixtures of failures latent within them.

The complexity of these systems makes it impossible for them to run without multiple flaws being present. Because these are individually insufficient to cause failure they are regarded as minor factors during operations. Eradication of all latent failures is limited primarily by economic cost but also because it is difficult before the fact to see how such failures might contribute to an accident. The failures change constantly because of changing technology, work organization, and efforts to eradicate failures.

Complex systems run in degraded mode.

A corollary to the preceding point is that complex systems run as broken systems. The system continues to function because it contains so many redundancies and because people can make it function, despite the presence of many flaws. . . .

Catastrophe is always just around the corner.

Complex systems possess potential for catastrophic failure. Human practitioners are nearly always in close physical and temporal proximity to these potential failures—disaster can occur at any time and in nearly any place. The potential for catastrophic outcome is a hallmark of complex systems. It is impossible to eliminate the potential for such catastrophic failure; the potential for such failure is always present by the system’s own nature.

Yes. This.

When people ask me if/why I’m conservative, my stock explanation is that my policy preferences have never been especially conservative, but my temperament is super-duper ultra conservative.

At heart, a liberal looks at the world and sees all the ways it can be better.

I look at the world and see all the ways it can get worse. I’m a tail-risk guy.

Which means that I spend a lot of time thinking about failure.1 This is one of the reasons why—if you don’t mind me saying so—I’ve been so consistently ahead of the curve for the last five years. It’s why we have the t-shirt.

And yet, historically, complex systems don’t always fail. To the contrary: They almost always work. The best explanation of this phenomenon comes from the philosopher Geoffrey Rush.

2. Happy Thanksgiving

When I look at the news today, one story that jumps out at me is the deteriorating situation in Ethiopia, where rebel forces are within 200 miles of the capital and the prime minister is heading to the front and calling on people to pick up guns and join him:

Those who want to be among the Ethiopian children, who will be hailed by history, rise up for your country today. Let's meet at the front.

This is not good. Ethiopia has 118 million people. It’s the 12th largest country in the world. And the picture you have in your head about Ethiopia may be outdated. Here’s a shot of the skyline of Addis Ababa, the capital:

Rebels marching on a modern city? A prime minister calling on civilians to grab AKs and fight in the streets with him? This is not good. This is a potential crisis. The kind of thing which creates instability and chaos.

I am concerned. We all ought to be concerned. This looks like a system failing.

But failure doesn’t always materialize. The wheels don’t always fall off the cart.

Most of the time, the cart keeps rolling along. Not smoothly—after all, the wheels are wobbling and the cart is rickety. But those things are always true. Because that is the nature of complex systems. I want to hit this note from Dr. Cook one more time:

The potential for catastrophic outcome is a hallmark of complex systems. It is impossible to eliminate the potential for such catastrophic failure; the potential for such failure is always present by the system’s own nature.

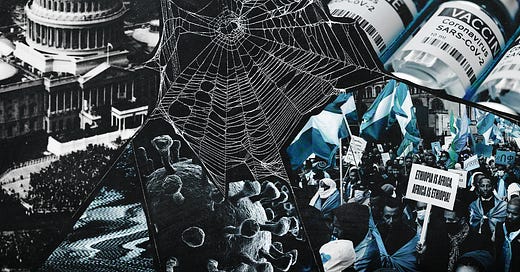

So that’s my Thanksgiving message to you.

Maybe the world doesn’t look so great right now. We’re still slogging through a global pandemic. We witnessed our first coup attempt since the Civil War. Our country has one political party that’s flirting with authoritarianism and another political party that’s a bumbling mess. Our friends and neighbors are at each others’ throats. Prices on everything are up. Things are NOT GREAT BOB.

Yet while the natural condition is one of insurmountable obstacles on the road to imminent disaster, most of the time it all turns out well.

How? It’s a mystery!

But it’s not really a mystery. The explanation is that the world is a complex system. We have always lived in a degraded state. And however grim this mode of operation might feel to us, the truly catastrophic outcomes are the exception, not the rule.

So Happy Thanksgiving, my friends. Don’t worry. I’ll be back to normal by Monday.

To go along with this uplifting message, I give you baby polar bears taking their first steps.

3. Lost

This sounds like almost as much fun as thru-hiking the AT:

One recent afternoon in Morocco, a fifty-nine-year-old former Royal Marine Commando named Phil Asher walked me into a desolate valley in the Atlas Mountains, shook my hand, and abandoned me. Asher, whom I had met only the previous evening, has a gray beard, a piercing gaze, and a bone-dry sense of humor. He teaches survival skills to people who have never fast-roped from a helicopter or killed their dinner. That morning, he had spent several hours educating me on the rudiments of living in the wilderness, alone. Now I was in the wilderness, alone.

The travel firm that organized my trip, Black Tomato, calls this experience Get Lost—a playful misnomer, since the idea is to do the opposite. A client is dropped somewhere spectacular and scantly populated, and challenged to find his or her way out within a given time period. From the moment that Asher left me in the valley, I was allotted two days to walk to a rendezvous point eighteen miles away, over and around mountains.

I had stuffed my backpack with everything that I thought I might need, within strict guidelines set by Asher: no matches, no tent, no phone. My pack contained clothes, paper maps, a compass, two G.P.S. trackers, spare batteries, notepads and pens, a big knife, a sleeping bag, flashlights, fire-lighting equipment, dried food, a few energy-rich snacks, three litres of water, a mosquito shelter, a roll mat, and a tarpaulin. I also carried an old Samsung handset with its sim card removed, so that I could take photographs. Asher reckoned that my bag weighed fifty pounds. I was going to trek for two days, at altitude, with the equivalent of my six-year-old daughter strapped to my back.

If I got hurt, I was to press an SOS button on one of the trackers, which also featured a rudimentary text-message capability, for sub-SOS emergencies. Asher would leave another three litres of fresh water at the site of my next camp, along with some firewood. Other than that, the assumption was that I’d navigate unassisted to the finish line.

“See you in a couple of days,” Asher said, as he left me. “Don’t do anything I wouldn’t do!”

One of my favorite books is The Logic of Failure. If that excerpt from Cook tickled you, this book will blow your mind.