What It Took to Fix the Democratic Brand Last Time Around

Today’s solutions will be different—but there are lessons worth learning from the story of the Democratic Leadership Council.

DEMOCRATS PONDERING WHAT TO DO NEXT after November’s defeat would do well to remember how the party came back the last time it was in the political wilderness.

After the 1988 election, respected political analysts believed Republicans had a lock on the presidency. Democrats had lost five of the previous six presidential elections. In 1972 and again in 1984, the Democratic candidate lost 49 states. In the three elections in the 1980s, the Republican candidate won landslide victories, averaging 54 percent of the popular vote and nearly 90 percent of Electoral College votes.

Democrats were out of power, out of ideas, and out of touch.

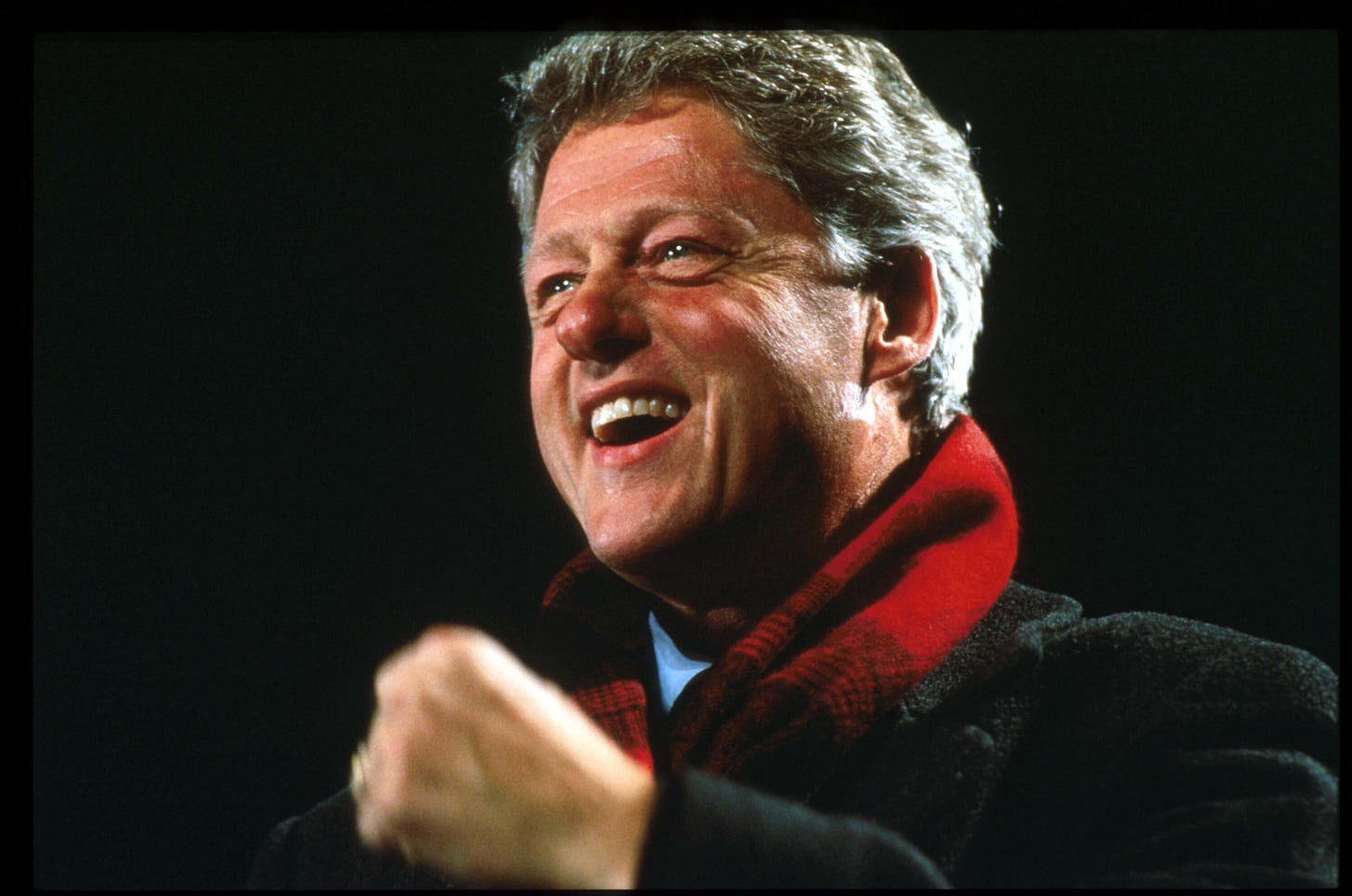

To change that, in 1985, I joined with a group of governors, senators, and representatives to form the Democratic Leadership Council. In 1990, Arkansas Governor Bill Clinton became chairman of the DLC.

Under Clinton’s leadership, we launched the New Democrat movement and forged a new policy agenda grounded in the values of opportunity, responsibility, and community,

Running as a New Democrat, Clinton ended the Democrats’ losing streak and reversed our fortunes in presidential elections. Between Clinton’s first victory in 1992 and Joe Biden’s in 2020, Democrats won the popular vote for president in seven of eight elections.

That streak was broken this year. While the Democratic party today is not at bedrock as it was after 1984 and 1988, the 2024 vote revealed disturbing trends that if not arrested could leave the party stranded again in the political wilderness.

It’s time for a new effort to fix the Democratic party’s brand.

This renewal effort needs to be led by a new generation of leaders—the outstanding crop of Democratic governors would be a good place to start—who can define challenges and solutions for the decades ahead. But they should keep in mind five things that made the DLC successful.

First, the DLC had a clear purpose: to develop an agenda, grounded in Democratic party principles, that could make us competitive again in the presidential elections. We believed that ideas mattered and that if we stood for the right things, the American people would once again turn to us for national leadership. It was no more complicated than that.

Second, the DLC offered Democrats a new face. Its members were among the party’s brightest rising stars. Under the DLC banner, they worked together and traveled the country to form a critical mass that became a new force in national politics. Nearly all had presidential aspirations, but they realized that for any of them to win the White House they needed to change our party first.

Third, the DLC was an insurgency. We built our own playing field and played by our own rules. We put on our own conferences and conventions. We arranged our own trips around the country. We raised our own money. We were neither part of nor sanctioned by the Democratic National Committee or the party’s other official campaign committees.

We pushed off not only Republicans but Democrats as well, where we believed Democratic orthodoxy must change. We were not afraid to ruffle feathers and take on intraparty fights when necessary to bring about change.

We shored up Democratic weaknesses on the economy, crime, and national security. We stayed out of day-to-day fights and concentrated on developing big, defining ideas—like national service (AmeriCorps), the earned income tax credit, welfare reform, charter schools, community policing, and reinventing government—that told voters that we were different from the Democrats they had been voting against for a quarter century.

Fourth, the DLC eschewed interest group and identity politics. We restored a sense of national purpose to a party that had become dominated by constituency and narrow interest groups. We built a diverse coalition around shared principles and ideas. We believed that if we put together a new agenda, grounded in New Democrat values, Democrats of all races, ethnic groups, and ideological persuasions would rally around our flag. That’s what we did—and that’s what happened.

Finally, we had an outstanding candidate. In the end, parties are defined by their presidential nominees. Bill Clinton carried the DLC message into the primaries, and it didn’t hurt that he proved to be a generational political talent.

It’s true that 2024 is not 1985. Re-creating the DLC of back then is not an option; any new effort to fix the party must address the challenges Democrats face today. But the next generation of Democratic leaders can learn a lot by studying why the DLC was so successful.