Frank Rizzo: The First Trump

Twenty years from now we’ll be fighting culture wars over attempts to honor Donald Trump.

1. Rizz

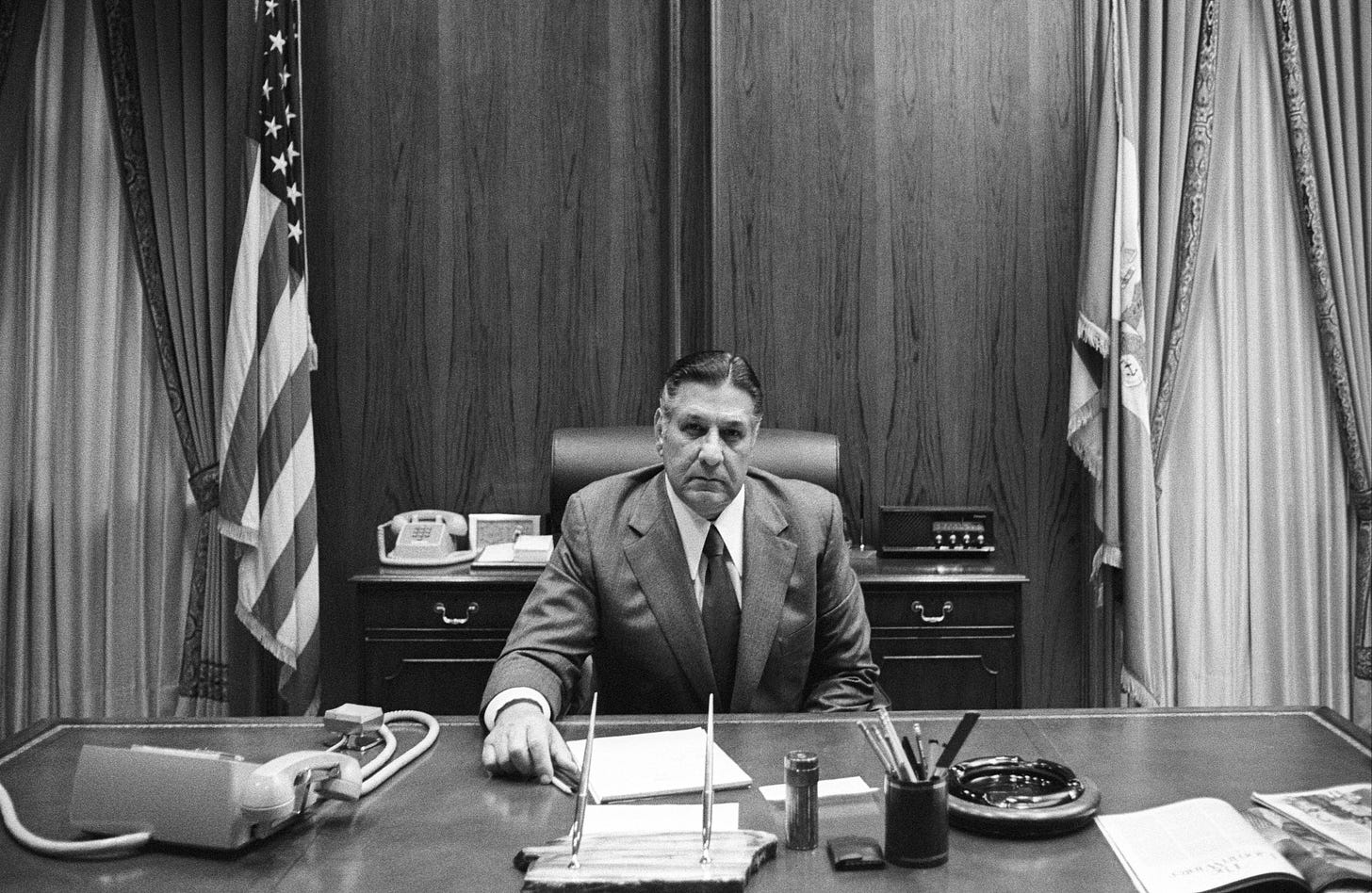

In 1998, a 10-foot bronze statue of former mayor Frank Rizzo was installed in the plaza across from Philadelphia’s City Hall. In 2020, the statue was taken down. Today, it looks as though the statue will be returned to the group that paid for it, the Frank L. Rizzo Monument Committee.

The fight over the Rizzo statue feels like a premonition of the year 2040. Some group will fund a heroic statue of Trump; other groups will oppose it; and in death, as in life, a bronzed Donald Trump will be both a symbol and source of culture war.

The reason this feels like a premonition is because Frank Rizzo was the first Trump.1

Read on and tell me if any of this sounds familiar.

When I was kid in Philly,2 Frank Rizzo was a joke. He was a bumbling old bigot on the local news. The Jerky Boys made him one of their recurring characters. Rizzo was a washed-up former politician who got pantsed by Wilson Goode—the city’s first black mayor—twice.

As I got older, I realized that Rizzo was no joke. He was one of the most pernicious, tyrannical mayors of the twentieth century.3

Rizzo was a cop, first and foremost. He joined the force in 1943 and became commissioner in 1967.4 In 1971, he resigned his post in order to run for mayor.

The ’60s and ’70s were times of racial upheaval in Philadelphia and Rizzo ran as a law-and-order candidate. He was a Democrat—all big-city politicians were Democrats back then—but he was unlike any modern Democrat. Rizzo was explicitly antagonistic to blacks. That was his brand.

For example, in 1970, Rizzo decided to have the offices of the Philadelphia chapter of the Black Panthers raided. He made sure the media was there. His officers strip-searched the African American members of the Panthers, in full view of the press. A picture of a naked black man ran on the front of the Philadelphia Daily News the next day.

And all charges against the Panthers were quickly dropped. Rizzo was sending a signal to white Philadelphians and while the entire episode seems ridiculous, you might say that Rizzo’s supporters took him seriously, if not literally.

Rizzo’s patron was Philadelphia mayor James Tate, who anointed Rizzo as his successor. Here’s a contemporaneous account of the 1971 Democratic mayoral primary, in which Rizzo was opposed by William Green:

Mr. Rizzo could not be prodded or wheedled into debating any issues, nor would he appear on the same platform with Mr. Green. He entered the race as the favorite with the endorsement of the city's ruling Democratic, organization, and contended debates would only give his opponent needed publicity.

He also avoided interviews, refused to answer written questions from the news media and civic groups and declined to join his opponents in testifying before the City Council on. Philadelphia's financial problems. . . .

Opponents contended the powerfully built, 50‐year‐old high school dropout lacked positions on housing, education and other urban problems facing the city or feared he might not be able to articulate them. He campaigned sparingly, usually scheduling only one appearance a day in white ethnic neighborhoods considered friendly to him.

But he started with a reservoir of devoted supporters who credited him with preventing the sort of black rioting that plagued other cities a few years ago.

That’s right: Rizzo was an ignoramus. A high-school dropout who refused to debate his primary opponents and had no grasp of how to actually run a city government. What he had was white resentment of a changing world, which he used to focus his campaign on getting Philadelphia’s city politics out of “extreme left field.”5 He actually said that his campaign was “to prevent the do-gooders and ultra-liberals from taking over.”

Rizzo delighted in triggering the libs. “I’ll make you a rich man,” he said in 1971. “I’ll give you $5 for every liberal who jumps off the Walnut Street Bridge when I’m elected.”

Who were these “liberals”? Some hippies, sure. But mostly Rizzo meant “black people.” Like a lot of people in media, Rizzo spoke in code words. We don’t do that at The Bulwark. We don’t do ads, either. We’re supported by readers who want to build the kind of media this country deserves needs.

Come and join us. This is the community you’ve been looking for.

Rizzo won the Democratic primary and then the general election. One of his first actions of mayor was to appoint his brother, Joe, as fire commissioner.

2. Strongman. Bully. Tyrant.

I don’t want to beat you over the head with the parallels, but let me offer you some choice quotes from Rizzo:

On capital punishment: “We’ve got to take the electric chair out of storage. I may do something in this area.” At another point, “I will personally pull the switch if they run out of people who want to do it. I'm available.”6

On the Black Panthers (circa 1971): “They should be strung up. I mean within the law. This is actual warfare.”

On Street Gangs: “Maybe we'll get some young strong policemen and meet them in the middle of the block and if they want to fight, fight.”

ON the Press: “I’m convinced the Philadelphia Inquirer and Daily News are against ethnic groups. I'm convinced that the Inquirer is out to destroy me and at the same time destroy Philadelphia.”

On Nixon: “I think he's the best President we ever had.”

On Political Enemies: “Just wait after November, you'll have a front row seat because I’m going to make Attila the Hun look like a faggot.”

But maybe you have to see Rizzo in action to understand him. Here he is on the street, calling a reporter a “crumb-bum” and challenging the guy to a fight.

This interview took place after Rizzo had trashed camera equipment in full view of police officers who did nothing as he destroyed someone else’s property. So much for “law and order.”

Things did not go great for Philadelphia under Rizzo. The ’70s were a bleak time for the city. Rizzo had hoped to move up to the governor’s mansion, but that didn’t work out.7 His tenure was marked by corruption, scandal, chaos, hostility to media, and an endless fixation on racial politics.

In 1975 he won re-election in a walk.

In his second term, the corruption grew. A federal lawsuit about the city’s discriminatory hiring practices was filed. Corruption in the police department got so epic that a movie (The Thin Blue Lie) would eventually be made about it. A recall effort was attempted, but failed. The polls showed Rizzo losing, so he went to court.

At first, Rizzo made specious arguments that the signatures on the recall petition were invalid. The city court found against him, calling Rizzo’s efforts to discredit the petition “incorrect,” “arbitrary” and “unconscionable.” So Rizzo switched tactics and filed a suit claiming that the recall provision in the city’s charter was a violation of Pennsylvania’s state constitution. In the end, the state supreme court ruled in Rizzo’s favor. The case was decided by a single vote. The opinion was written by a justice whom Rizzo had helped get elected to the court in 1971.

At the time, Philadelphia’s city charter limited mayors to two consecutive terms. Rizzo tried to change that. In 1978, he pushed for an amendment to the city charter that would allow him to run for a third term in 1979. The ballot initiative failed.

Rizzo left office and immediately began taking money as a consultant to one of the city’s public utilities while he plotted his return. He ran for mayor again in 1983, but by this time the demographic tide had turned. Rizzo lost the Democratic primary to Wilson Goode, who would become Philadelphia’s first black mayor.

Losing to an African American man did not sit well with Rizzo. He switched parties and became a Republican so he could face off against Goode in the 1987 election. Goode beat him again.

In 1991, Rizzo ran again. He won the Republican primary again, too. Philadelphia Republicans did not seem to mind losing the general election with Rizzo on the ticket. Instead, they seemed to delight in having Rizzo as the avatar of their resentments.

Amazingly, after winning the primary, Rizzo attempted to remake himself as a friend of Philadelphia’s black community. I don’t know whether it was karma or the wrath of an Old Testament God, but this makeover did not succeed and Rizzo dropped dead of a heart attack in a bathroom at his campaign’s headquarters four months before the November election.

Because of my age, I only ever knew Rizzo as a joke. I grew up in a political world in which Rizzo was a buffoon, a loser, and the embodiment of the Republican party in Philadelphia.

It took years for me to understand that for a certain kind of Philadelphian, Rizzo might Vito Corleone, Pericles, and Rocky all rolled into one. They loved him. And the wellspring of their love was that he hated all of the same people that they hated.

Rizzo wanted cops to beat on blacks and hippies. He opposed public housing projects. He made sure that city jobs went to the right people. Rizzo’s appeal wasn’t policy—he didn’t understand urbanism or management theory. And it wasn’t results—Rizzo’s years were among the worst and most depressing in Philadelphia’s history, with trash-strewn streets, vandalism and gangs, high crime rates, and high unemployment.

Rizzo’s political secret sauce was that he united Philadelphia’s various white ethnic groups—the Italians, the Irish, the Poles, the Germans—against the city’s rising blacks.

Rizzo became the focus of the admiration of not only Italian-Americans but of every other ethnic group in Philadelphia. The only exception was the African-American community. At the heart of Philadelphia’s political culture, Lombardo argues, was the racial antagonism of white, blue-collar ethnics toward the city’s growing African-American population. . . .

In 1960, Philadelphia was the fourth-largest American city, and it was divided into a patchwork of hundreds of neighborhoods. These were fiercely patriotic, or, depending on one’s perspective, maniacally localist. Their inhabitants were employed mainly in light manufacturing. As blue-collar Philadelphians saw it, they enjoyed comfortable lives and were deeply suspicious of anything that might change them or any outsiders who might enter into their communities. African-Americans arriving during the ’50s—the Great Migration came late to Philly—were regarded both as competitors for jobs and interlopers into the clannish neighborhoods. “Defense of neighborhood,” Lombardo writes, “was at the root of nearly every conflict that contributed to the transformation in white working- and middle-class politics in the 1960s and 1970s.” . . .

Frank Rizzo became the focus of this adulation—and ultimately the vehicle by which his fellow blue-collar whites could revenge themselves against both black Philadelphians and despised white-collar elites.

It didn’t matter how badly things went in Philadelphia under Rizzo. His people wanted him because of his hatred and corruption and the chaos that followed him. And they loved him so much that, even after history had left them behind, they wanted his statue across from City Hall and were willing to fight to keep it there.

So no, Frank Rizzo wasn’t a joke. He was a dangerous, pernicious man who attempted to subvert the political order at the local level by harnessing the power of populist grievance.

He failed. But only because people opposed him and worked over the course of 20 years—20 years—to keep him away from power.

We’re doing that kind of work right here, every day. And we’re giving almost all of it away for free, because we know that you can’t stop guys like Rizzo from behind a paywall. We’re able to do this because our readers have come together to build this place and make it a community.

Come and join this thing of ours. We’ve got a democracy to save.

3. Sizzlechest

Some longform writing about Rizzo, just to round out your day.

Scholars are increasingly studying American fascist movements like Trumpism in terms of white Christian nationalism—an ideology that sees American citizenship as typically white and Christian, with all others locked in a subordinate position.

I wanted to look at how this framework could be applied to [Frank] Rizzo, and called in Prof. Anthea Butler, an expert in this field, to help. Butler’s book White Evangelical Racism makes the case that you can’t disentangle conservative Christianity in the US from white supremacism. It’s not about the theology; it’s about a background set of assumptions that insist that white/Christian identity should always be on top.

Butler is especially interested in how this is advanced by Protestants. So I asked her about whether there could be a Catholic version of white Christian nationalism. She enthusiastically confirmed that there could be, but with a twist: white Catholic nationalism, she told me, has detached itself from the Catholic social justice tradition—and even, in many ways, from church teachings themselves—and become a hollow clone of conservative white evangelicalism, fixated on domination and control at all costs. As she said in our interview, “social justice and other issues that Dorothy Day does [are] not recognizable to them. They’re more Pat Buchanan-style Catholics… They want God and country. They want law and order. These things sync up with evangelicals and other white Christian nationalists.”

Both Catholic and Protestant versions of white Christian nationalism supersede morality; they fixate on winning at all costs. Rizzo fits this mold. He was strongly associated with his Italian identity, and one of his core policies was protecting Catholic parochial schools from city interference. It wasn’t really about Catholic theology or Catholic ethics. Instead, it was about Catholicism as an identity—closely wrapped up with whiteness—that was presented as a flag to rally around.

Correction, May 22, 2024, 12:43pm: The article originally stated that the Rizzo polygraph scandal was caused by a conflict with a local reporter. The conflict was actually between Rizzo and a rival politician, Peter Camiel.

I am not the first person to make this observation. See Jake Blumgart.

On the Jersey side, about 7 miles from Philly’s City Hall.

Not an exaggeration. In the book The American Mayor, historians ranked Rizzo as the fifth-worst American mayor between 1820 and 1993. I’m not saying that this ranking is official—I’m just saying that if historians have you in the conversation for worst mayor in 170 years, then you’re pretty terrible.

Why wasn’t Rizzo in the war? He served 19 months in the Navy before securing a medical discharge for diabetes insipidus.

At the risk of belaboring the obvious, this was code for “black people.” Philadelphia had been run almost continuously not just by Rizzo’s fellow Democrats, but by Rizzo’s personal class of patrons.

While Pennsylvania had capital punishment until 1999, the city of Philadelphia did not. Why would a mayoral candidate posture about bringing back capital punishment? Maybe for the same reason a president would claim he could deport 11 million migrants.

Midway through Rizzo’s first term he got into an altercation with a rival Democratic politician. Rizzo accused the other pol, Peter Camiel, of lying. Camiel countered that it was Rizzo who was lying and proposed that they both take polygraph tests. Rizzo, a great believer in lie detectors, agreed. Camiel passed and Rizzo failed.

This was his big reality-TV scandal.

I now have a sudden urge to call somebody a "crumb bum."

Brilliantly done JVL and an especially dark and tragic look back (while looking forward as well). As depressing as it all was, one sentence gave me hope: "Rizzo dropped dead of a heart attack in a bathroom at his campaign’s headquarters."

We can all still hope God is looking down, smiles and will work his magic once again.