[On the August 18, 2023 episode of The Bulwark’s “Beg to Differ” podcast, host Mona Charen asked guest Kristin Du Mez, author of Jesus and John Wayne, about the trends that led to evangelicals backing Donald Trump.]

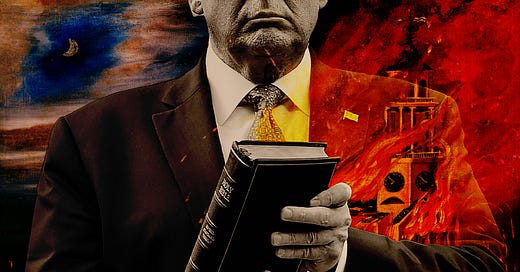

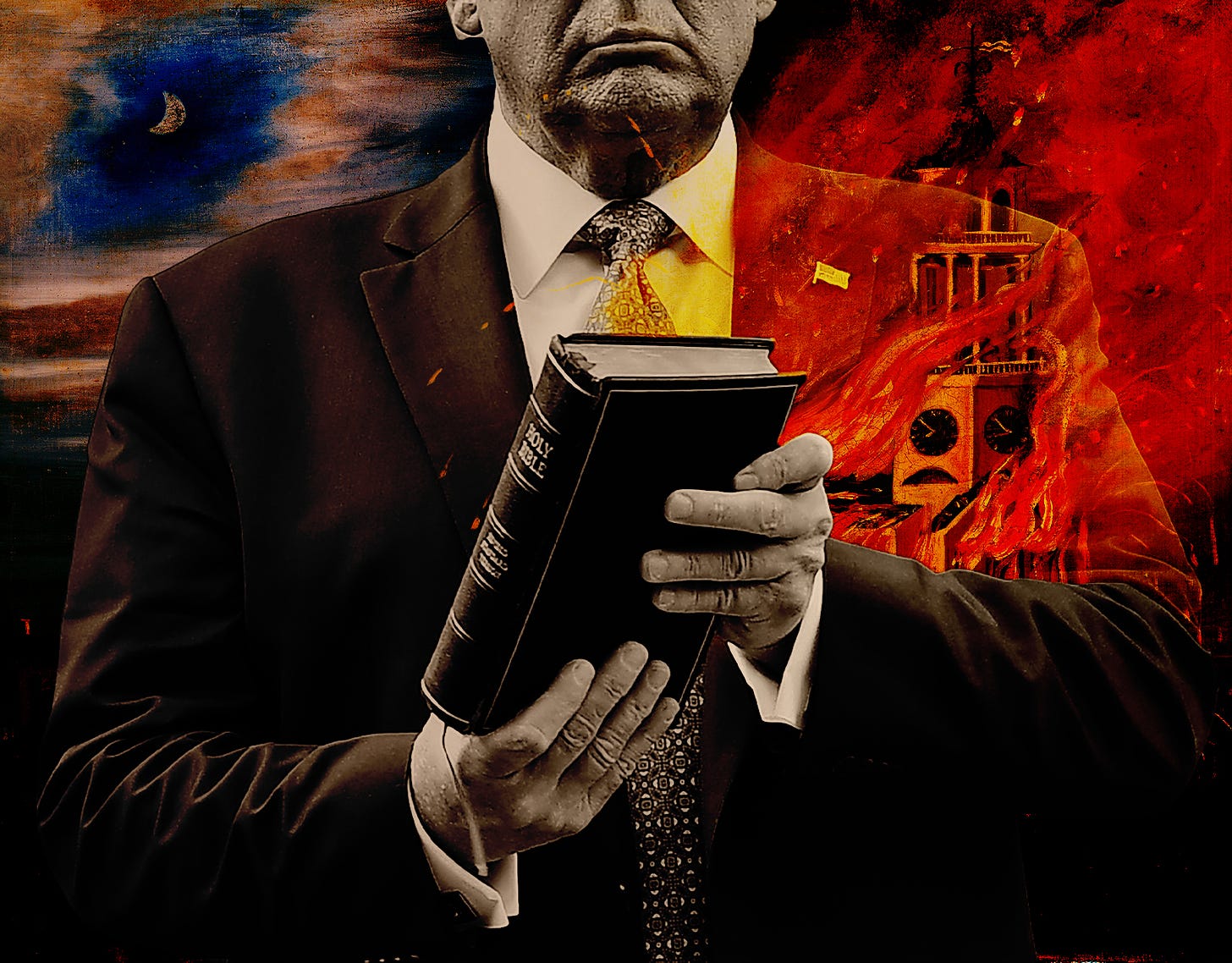

Mona Charen: Kristin . . . your thesis, as I understand it, is that the evangelical embrace of Donald Trump is not a departure from their beliefs. It’s the fulfillment of their beliefs. Is that right?

Kristin Du Mez: Yes, and that’s a good synopsis. And I came to that conclusion by paying attention to evangelical popular culture, and particularly to evangelical ideas about masculinity. And I started noticing more than twenty years ago a growing embrace of a very kind of militant, rugged, even militaristic conception of what it meant to be a Christian man, a kind of warrior. And I traced that up to the present and heard so many echoes of that in evangelical support for Trump—he was their ultimate fighting champion, who would do what needed to be done to advance their aims.

Charen: Now this is interesting, because at the same time you’re saying this was happening within the evangelical world . . . there was a lot of worry that masculinity itself was in crisis in the larger society. So what’s the interaction there between evangelical pop culture and ordinary regular pop culture?

Du Mez: Yeah, evangelicals are Americans and evangelicals do influence other Americans. So, it’s always important to kind of keep those together, to hold those together. That said, you can see in the recent history of evangelicalism kind of an ebb and flow of perceptions of masculinity and what’s wrong with masculinity.

So if you go back to the 1990s, you had the rise of Promise Keepers and an evangelical men’s movement, where their preferred masculinity tended to be more of a “tender warrior” motif or a “servant leader”—a kind of kinder, gentler one that maybe went hand in hand with a compassionate conservatism.

And then you see that pendulum start to swing, and by the early 2000s, an embrace of a much more of this kind of “warrior” mentality. And you can see some similar patterns in the broader culture. And today, you kind of see some parallels—in terms of what we see happening in evangelicalism and really brought to mainstream evangelicals through religious culture—and some of what we see happening in some more fringe spaces, like the “manosphere,” both really embracing this kind of rugged masculinity that is not uncommon if you look at the history of authoritarianism, to be frank. It kind of goes hand in hand with a reactionary populism. . . . You see it . . . across the spectrum, both in religious and in secular spaces.

Charen: How do you analyze the dramatic change among evangelicals between the Clinton era and today? So, in the Clinton time, leading evangelicals, and I think people in the pews as well, had a very strong view that ethics and personal morality were incredibly important in a leader. And they felt strongly that Bill Clinton was failing them, failing the country in that regard. Now, during the Trump era, polls show that there’s been a complete reversal, and that evangelicals are the least likely to think that personal morality is important in a leader.

Du Mez: Yeah, that survey data really does depict in dramatic style [how] it’s easy to kind of stand up for moral values when Bill Clinton is under critique. It’s proven much more difficult in recent years, particularly around Donald Trump. . . .

One of the things that I saw in my research is that this is not a new trend. If you look at how many conservative evangelicals responded to abusive leaders, abusive pastors in their own churches and in their own organizations . . . time and time again you see evangelical communities ending up defending perpetrators of abuse—of sexual abuse, of abuse of power—and doing so in the name of protecting the witness of the Church, [and] blaming women for leading men on or for seducing men. All sorts of excuses, really.

And that was stunning to me in my research. And what I saw is that there is a longer pattern here, of protecting men with power, who are perceived to have an important role to play in protecting and defending the faith, [and] protecting Christianity. And that’s exactly the rhetoric that we have heard and continue to hear around somebody like Donald Trump.