From Intellectual Dark Web to Crank Central

Was the loose-knit band of rebels always destined to go fringe?

AMID THE RECENT CONTROVERSY about Ben Shapiro’s Daily Wire website finally dropping conspiracy theorist and antisemitic ranter Candace Owens, one minor but fascinating detail went unnoticed: Six years ago, both Shapiro and Owens had cameos in a much-ballyhooed New York Times Magazine article that introduced the world to the “Intellectual Dark Web”—mathematician Eric Weinstein’s semi-facetious label for an informal network of authors, journalists, and academics who saw themselves as “heretics” and “renegades” in rebellion against the establishment. Shapiro, then an anti-Trump conservative, was briefly discussed as an IDW figure; Owens, then a rising “black conservative” activist/provocateur whom some in the IDW saw as a potential ally, was held up as a warning against embracing “cranks, grifters and bigots.” (In those days, Owens was not yet talking about “Jewish gangs” in Hollywood, but she was already claiming that immigrants are stealing jobs from black Americans and comparing celebrities who support the Democratic party to plantation slaves.)

Although the May 2018 article’s author, Bari Weiss, was largely sympathetic to the IDW, she wondered, “Could the intellectual wildness that made this alliance of heretics worth paying attention to become its undoing?”

In 2024, this question seems uncannily prescient.

Of the IDW stars profiled in Weiss’s article, several—former Evergreen State College biology professors Bret Weinstein and Heather Heying, a married couple; Canadian psychologist and bestselling guru Jordan Peterson; podcaster Joe Rogan—have devolved into full-blown cranks. In a recent podcast episode, Peterson goes full Alex Jones on COVID-19 vaccines, claiming they caused more deaths than the “so-called pandemic,” and barking his skepticism about childhood vaccination in general. Weinstein and Rogan recently used Rogan’s podcast, which has an audience of millions, to push not only the notion that mRNA vaccines, including the COVID-19 ones, are lethally dangerous but the idea that HIV isn’t the real cause of AIDS and that HIV-skeptical maverick scientist Kary Mullis’s death in 2019 may have been engineered by Dr. Anthony Fauci. The ranks of the cranks also include author and podcaster Maajid Nawaz, briefly mentioned in the original IDW piece as a “former Islamist turned anti-extremist activist”—now a vaccine and 2020 election conspiracy theorist, and most recently seen boosting the Kremlin’s efforts to link Ukraine to the ISIS terror attack in Moscow.

Not surprisingly, the IDW’s slide into crankism has coincided with a slide into Trumpism—or anti-anti-Trumpism pushed to degree where it becomes indistinguishable from Trumpism tout court. Peterson has long sympathized with Trump as an anti-establishment rebel. Bret Weinstein, once a Bernie Sanders-supporting leftist, now says that he “appreciate[s] Trump” and would consider voting for him if he just got more fully on the Covidiot bandwagon (and agreed to pardon Julian Assange). In 2020, Weinstein peddled “concern” about the possibility of “substantial fraud” in the election. Today, he suggests that electing an “obviously senile” Biden amounts to a coup handing power to “a cabal of unelected powerbrokers” from the Democratic National Committee, and posts cryptic tirades against Joe Biden supporters.

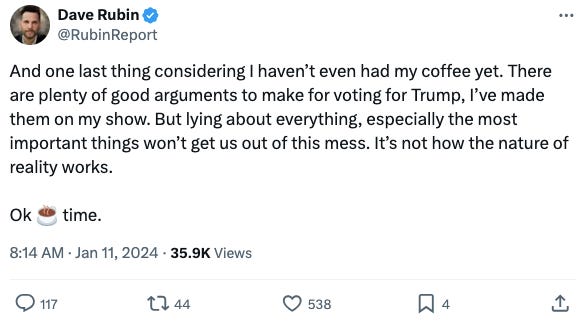

Meanwhile, another IDW star profiled in the original article, erstwhile progressive Dave Rubin, the comedian and podcaster who voted for Libertarian Party candidate Gary Johnson in 2016 and promised to be “the first to hold Trump’s feet to the fire once he’s in office,” told Fox & Friends in 2020 that he was voting for Trump as “the last bulwark to stop the radical left.” As for holding Trump’s feet to the fire … well, he did, in 2018, call out Trump on Twitter for suggesting that video games cause violence (a real profile in courage!). More recently, as a Ron DeSantis supporter, Rubin ripped into Trump for spouting “seriously dishonest bullshit” and treating his base like “a bunch of morons.” But don’t worry: Rubin still thinks there are “plenty of good arguments to make for voting for Trump,” even if he’s prone to “lying about everything.”

Oh, and Rubin is among those who have made the bizarre and baseless insinuation that “wokeness” led to the collapse of the Francis Scott Key Bridge in Baltimore.

As for Ben Shapiro, there never was a story of more woe: Described as “an anti-Trump conservative” in the original IDW article, he’s now not just voting for Donald Trump but even cohosting a fundraiser for him, and he told his podcast audience that he would “walk over broken glass to vote for [Trump]” because Joe Biden “is the worst president of my lifetime.”1

Not all of the IDW-associated figures featured in Weiss’s article have veered crankward. American Enterprise Institute senior fellow emeritus Christina Hoff Sommers remains eminently sensible (and an anti-Trump centrist). Two others, Sam Harris and Claire Lehmann, have openly broken with and criticized the IDW. Harris—a philosopher, neuroscientist, prominent atheist, and author—said in November 2020 that he was disassociating himself from the IDW label over other IDW figures’ embrace of Trump’s election-fraud claims and other conspiracy theories, noting that some of them were “sounding fairly bonkers.” Harris has made even sharper criticisms since then, especially over the anti-vaccine rhetoric. Lehmann, who founded the online magazine Quillette as a hub for heterodoxy in 2015 and was featured as the “voice” of the IDW in Politico in late 2018, first clashed with some fellow Dark Webbers over her willingness to publish articles, including one by me, criticizing certain aspects of the IDW—such as a tendency toward its own brand of groupthink and tribalism—as well as some of its members, such as Dave Rubin. (It turned out Lehmann meant it when she told Politico she didn’t want Quillette to be an echo chamber.) More recently, Lehmann has talked about the IDW’s fracturing over COVID-19, conspiracy theories, the war in Ukraine, and other issues.

If the IDW ever really existed as anything more than a catchy, not-quite-serious brand name for an informal intellectual community, there is little doubt that it no longer does. A recently published short book by University of Sydney lecturer Jamie Roberts that charitably examines the IDW and its contributions to political dialogue, The Way of the Intellectual Dark Web, refers to it in the past tense. Onetime IDW fellow traveler Christopher Rufo wrote its obituary a year ago, arguing that the IDW fell apart because some of its members found Trump too icky and orange, some were unwilling to part ways with establishment science on COVID, and most of the rest lacked Rufo’s appetite for using political power to vanquish perceived enemies.

But while the IDW may be dead, its ghosts continue to haunt our political and cultural scene, and its rise and fall are worth examining. Was it a worthy project gone bad, or was it always a fraud based on spurious grievances? Why have some people gone off the deep end and others pulled back from the brink? Does the IDW have a redeemable legacy? And has its first chronicler, Bari Weiss, managed to avoid the perils that she warned about in the 2018 piece?

WHEN WEISS’S ARTICLE, “Meet the Renegades of the Intellectual Dark Web,” first appeared, it elicited strong reactions—and some patently unfair attacks. As I noted in Arc Digital at the time, a number of Weiss’s detractors, including her then–New York Times colleague Paul Krugman, seemed to assail an imaginary article that they believed she had written: an IDW advertorial that depicted its members as silenced and/or oppressed martyrs. In fact, while Weiss wrote that some IDW intellectuals had been “purged” from institutions grown uneasy with dissent, one of the points of the piece was that the new media ecosystem had allowed them to find lucrative platforms and receptive audiences elsewhere.

Some early critics, such as Henry Farrell at Vox, argued that the stars of the IDW were “white intellectuals” resentful of being displaced from a dominant cultural position and having to endure pushback against their ideas, including sexist and racist ones. Columbia University professor and author John McWhorter, a liberal critic of the progressive left with no connection to the IDW (despite jokingly describing himself in a 2018 podcast as part of “the black wing of the Intellectual Dark Web,” a casual comment which he ruefully notes has “resonated for years”), is harshly dismissive of critiques like Farrell’s. “Nonsense,” he wrote in an email to me last month. “It’s [Critical Race Theory]-speak, this idea of white people circling their wagons.”2 One could also argue that the stars of the IDW were far too eccentric to have been in a culturally dominant position prior to the cultural shift toward identity politics and social-justice progressivism in the 2010s. Peterson had been an obscure University of Toronto psychologist whose Jungian psychology–based first book, Maps of Meaning, reportedly sold about a hundred copies when it was first released in 1999; Weinstein and Heying had been faculty members at a tiny, very left-wing liberal arts college in Olympia, Washington.

The IDW figures were hardly the only public intellectuals critical of the rise of illiberal progressivism in academia, social media, and mainstream journalism. Numerous liberals who were not a part of the IDW coterie, such as New York magazine’s Jonathan Chait, the Atlantic’s Anne Applebaum, and Canadian critic Phoebe Maltz Bovy were concerned about the phenomenon at the time. What distinguished the IDW figures was their outsider status. Some of them, Weiss wrote, were “purged from institutions that have become increasingly hostile to unorthodox thought,” and they came to define themselves by, and even take pride in, their exile, finding a new community there.

One may debate the extent to which specific narratives by IDW figures were overdramatized; Weinstein and Heying’s tumble into crackpottery, for instance, has made some former supporters question the reliability of their account of their IDW ‘origin story,’ which involved turmoil at Evergreen in 2017 after Weinstein challenged a proposed “Day of Absence” for white faculty and students. For the record, I first had such questions several years ago when I interviewed the couple, around the time Weiss’s IDW piece came out, for an article I ended up shelving. Weinstein and Heying told me of a colleague and her students being ejected from a no-whites-allowed campus event on that day; the faculty member herself recollected that she and the students made a voluntary exit after realizing that the event was meant as people-of-color-only, despite being told they were welcome to stay. When I relayed this back to Weinstein and Heying, they quickly concluded that the Evergreen administration had pressured the woman into changing her story—not an impossibility, but also not a claim that could be accepted without evidence.

However, while there is some debate about whether the one-day white absence from the Evergereen campus was meant to be voluntary or enforced, the activist students’ ugly physical intimidation of both Weinstein and the college president was captured on video. And there were plenty of other well-documented incidents of intolerance and groupthink on college campuses, in literary communities, and elsewhere (e.g., the media frenzy over British scientist Tim Hunt’s alleged sexist tirade at a luncheon honoring women in science, later confirmed to have been a self-deprecating joke about his own supposed male chauvinism). In other words, the IDW was to some extent pushing back against trends that deserved a pushback.

But again, plenty of people—Chait, Applebaum, Bovy, McWhorter, and other journalists, commentators, and academics—managed to push back against those trends and not, as McWhorter put it to me, “drift into poised lunacy.” Some IDW figures avoided that drift; some IDW-adjacent people who were not part of Weiss’s article were at its forefront. (James Lindsay, anyone?)

Partly, it comes down to personalities. It seems likely that Weinstein and Peterson were a bit kooky before they traveled the full distance to unhinged. Joe Rogan, whose massive audience and folksy just-asking-questions manner ensure that he can still book respectable guests, was prone to falling for the dumbest conspiracy theories long before the IDW was a gleam in Eric Weinstein’s eye. (From 2012 to 2017, Rogan was a moon landing denier—no, really.) In an email last month, Sam Harris told me:

The IDW was never a cohesive group. It was a tongue-in-cheek name for a dozen people who were inclined toward a certain style of conversation—essentially a rejection of political correctness—mostly in podcast form. The only thing uniting these disparate characters was their unwillingness to be cowed by attacks from the Left. Several in the group (the imbeciles) were quite eager to pander to the Right. . . . Several people who got pulled into our orbit were bad actors from the beginning—Trumpist grifters and conspiracists—and a few of the original members got corrupted or revealed their truer, baser selves.

IT SEEMS LIKELY, IN RETROSPECT, that the IDW concept itself was conducive to such corruption. Bioethicist Alice Dreger, who left Northwestern University in 2015 with complaints about administrative censorship and has been targeted for campus protests over accusations of “transphobia,” refused Weiss’s invitation to be included in the IDW article for several reasons. The very framing, she wrote, implied that the featured “heretics” were huddling in dark corners or catacombs to exchange forbidden opinions; in Dreger’s view, it also valorized opinions over facts and easily lent itself to prioritizing “clicks, skirmishes, and dramatic photos at sunset”—a dig at the cringey pictures illustrating the article, which showed its protagonists in eerily dark forest settings, clearly meant to convey that there was something shadowy and forbidden about their activity.

McWhorter also feels that “the ‘dark web’ moniker was unfortunate because it implied connection with the truly evil forces on what was being discussed with that name at the time.” (The term “intellectual dark web” was allusion to the “dark web,” itself a term that has since fallen into disuse, which referred to hidden, anonymized parts of the internet where one could buy hacked personal information, stolen credit cards, illegal guns and drugs, etc.)

When being an outlaw or even just a permanent outsider becomes central to one’s identity, contrarianism and reflexive suspicion of anything associated with the “establishment” can easily become not only a temptation but a habit, even a norm. The correct observation that mainstream media have often uncritically recycled progressive claims about race and gender becomes a steppingstone to the assumption that the media lie about everything (COVID, the 2020 election, Ukraine. . .) and that the rebels are champions of suppressed truths. Next thing you know, you’re hawking Ivermectin as a COVID cure or regurgitating Kremlin talking points on the war in Ukraine.

Why some people are less susceptible to this mentality than others is a question that undoubtedly has multiple answers. In Harris’s case, for instance, his mainstream success as a bestselling author despite left-wing blowback on such issues as his criticism of Islam may have made him less receptive to anti-establishment grievance. One’s character and habits of critical thinking are undoubtledly relevant as well. Quillette’s Lehmann told me in a Zoom interview that she started out as “broadly anti-anti-Trump” after the 2016 election and assumed that warnings about Trump refusing to accept a loss in 2020 were “hysterical nonsense”—until it actually happened. So did the invasion of Ukraine, another point on which the mainstream media narrative had turned out to be correct. “It really made me reassess my priors,” says Lehmann. “I realized that I had had a blind spot on those two huge issues. So I updated my beliefs.” Others preferred to adjust the facts to fit their priors—or, Lehmann suspects, pretended to do so “because they don’t want to lose the audiences they built.”

That’s the “audience capture” phenomenon—a term that, ironically, appears to have been coined by the same Eric Weinstein who christened the IDW concept. In a polarized political climate, the IDW attracted a base of primarily right-wing fans intensely hostile to all things “establishment.” To those fans, opposition to Trump, rejection of the “stolen election” lies, support for mainstream science and public health measures on COVID, and eventually even support for Ukraine in its defense against Russia’s war of aggression signaled betrayal and selling out. Harris, who left Twitter in late 2022, was the object of intense vitriol from former fans directed at his alleged “Trump Derangement Syndrome.” (“Trump broke him” is another go-to trope.) Lehmann, no stranger to social media wars, told me that the “vicious response” she received for pushing back against hyperbolic claims that the COVID lockdowns in Australia were Nazi-like was “one of the most difficult experience I’ve had on social media, or to do with Quillette in general.” Yet Lehmann also believes that Quillette ultimately benefited from shedding much of its hard-right following as a result.

It may be that, because of the dynamics in today’s intellectual and political marketplace, any commentator, media outlet, or group that opposes the illiberal left but doesn’t explicitly oppose far-right Trumpian populism in in danger of being co-opted by it.3

THESE ISSUES ALSO HAVE SOME relevance to Bari Weiss’s own career six years after she first introduced the IDW to the wider public. In July 2020, Weiss quit the Times in protest against the forced resignation of her boss James Bennet, then the paper’s editorial-page editor, over an op-ed he had published by Sen. Tom Cotton (R-Ark.). Weiss subsequently set up a Substack newsletter that became a multi-contributor magazine, the Free Press, and a podcast—thus migrating into the independent media-land of the IDW.

The Free Press, whose staff includes veteran journalists such as Emily Yoffe, Peter Savodnik, Eli Lake, and Nellie Bowles (who is married to Weiss), was recently described by Chait as “interesting as well as frequently infuriating.” Chait grants some truth to the project’s basic premise: that a lot of mainstream media have abandoned objectivity on identity-related issues (whether due to ideology, activist pressures, or both), and that the resulting distortions in news coverage have left a gap to be filled.4 He also believes that the Free Press has sometimes filled this gap in important ways—for instance, with a hugely controversial 2023 piece in which Jamie Reed, a former case manager at a youth gender clinic in St. Louis, alleged that many children were being rushed into hormone treatments without proper counseling or mental health examination. Many progressive journalists rushed to accuse Reed, a self-identified “queer” leftist married to a transgender man, of promoting a “right-wing transphobia panic”; but a New York Times investigation later corroborated many of her claims.

Yet Chait also points out that the Free Press’s stance with regard to Trump has been increasingly “defensive,” portraying him as a victim of left-wing and elite animus—one article, by Martin Gurri, even predicts that Trump will be “broken on the wheel of elite hatred” before Election Day—and complaining about his voters being “villainized.” While the Free Press has lamented attempts to remove Trump from the ballot because of his role in the January 6th insurrection, it seems to have nothing to say about Trump’s increasing embrace of the “J6 patriots” on the campaign trail.

This is likely the result of both contrarianism and audience capture: Judging by the comments on the Free Press site, the MAGA right certainly makes up a substantial portion of its readership.5 Either way, the Free Press’s current anti-anti-Trumpism is a startling contrast to Weiss’s stance in 2018, when she pointedly criticized IDW members who “talk constantly about the regressive left but far less about the threat from the right” and quoted Harris’s barb against those who claim to care about truth but never have anything to say about Trump, the serial truth-assaulter.

Harris, for what it’s worth, stressed in our email exchange that while he may not agree with everything in the Free Press, he still admires it and wants it to succeed. So do I; but real success requires avoiding blind spots this big.6 The bottom line is that the site sometimes stumbles into the same pitfalls about which Weiss warned the IDW, including the embrace of “grifters”: Last August, Weiss conducted a spirited but respectful interview with then–presidential candidate Vivek Ramaswamy, the guy who not only thinks that Vladimir Putin and Volodymyr Zelensky are “two thugs” vying for turf in Eastern Europe but has repeatedly suggested that January 6th was an “inside job” and flirted with 9/11 “trutherism.” Obviously, a presidential candidate, even one with no chance of winning, is a legitimate subject for an interview. But Weiss treated Ramaswamy as an interesting and fresh voice on the political scene—and, despite some pushback on the Ukraine issue, did not delve into his more extreme statements. That’s not just an interview, it’s validation—and misleading validation at that.

WHAT, IF ANYTHING, is the IDW’s legacy almost six years later? Both Lehmann and Harris believe that recent cultural trends make a community of heterodox intellectual unnecessary. Lehmann sees “real progress in the media ecosystem opening up,” though she believes heterodox advocacy is still necessary in academia. Harris says he is “hopeful that we have seen peak ‘woke’ and that the pendulum of sanity is in the process of swinging back,” especially after the social justice left has “thoroughly discredited itself” after the October 7th attacks in Israel. (He warns, however, that “if Trump gets re-elected, this will change.”) And indeed, many of the issues IDW members were championing six years ago—such as freedom of speech and the overreach of progressive “cancel culture,” or the need to address the struggles of many boys and men in a world of changing gender roles—are now the subject of flourishing mainstream discussion. Even controversial aspects of transgender advocacy, from youth gender therapy to denials of the reality of biological sex, are being debated in the pages of the Atlantic and the New York Times.

Ironically, this cultural shift probably contributed to some IDW figures’ slide into cuckooland. What do you do when you define yourself as a rebel and an outsider but the “dissident” ideas you’ve championed have gained “insider” respectability? One possible response is to cling to outsider status by moving further to the fringe: the 2020 election was stolen, the COVID vaccine kills massive numbers of people, Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau is gay.

Whether the figures involved with the IDW can take credit for opening up the Overton window, though, is doubtful. Stating provocative ideas? That’s not much of a legacy, since “social media leave so many other people Telling Truths as well as those guys were trying to do,” McWhorter observes wryly. Putting campus illiberalism on the map? Maybe Bret Weinstein and Heather Heying deserve some credit for that, but at least as much is owed to Yale faculty members Nicholas and Erika Christakis, who are not affiliated with the IDW and also not crazy. Making the case for intellectual tolerance? The 2020 Harper’s magazine “Letter on Justice and Open Debate,” which drew some of the same ‘white people protecting their privilege’ objections as the IDW, unquestionably had a far greater impact.

Thus, in the end, it seems that the IDW’s principal legacy today is a cautionary tale. Don’t get caught up in a “dissident” identity, especially if you live in a liberal society (however flawed). Don’t confuse skepticism with contrarianism, or truth-seeking with conspiracy theory. Stay away from toxic allies (you know the ones: the cranks, grifters and bigots). And, of course, never go full MAGA.

Eight years ago, Shapiro wrote that Barack Obama was “the worst president in American history.” If Shapiro thinks Biden is worse than Obama, then logically he thinks Biden is the worst president in American history, which at least bodes well for the reputations of James Buchanan and Andrew Johnson.

In this instance, McWhorter is referencing actual critical race theory, not the catch-all buzzword pushed by Rufo et al.

This can be seen as a variation on British historian Robert Conquest’s “second law of politics” (often attributed to British conservative pundit John O’Sullivan), which holds that any organization not explicitly right-wing will sooner or later become left-wing.

As an example, I analyzed some of these problems in the coverage of the racial justice protests and riots in the summer of 2020 for Arc Digital.

For instance, the comments on Savodnik’s recent piece, about the one-year anniversary of the arrest of American reporter Evan Gershkovich in Russia, are depressingly full of whataboutism about January 6th defendants.

Other recent articles suggest that the Free Press’s skepticism of mainstream media narratives can lead it down the garden path of embracing factually shoddy and essentially partisan “heterodox” claims that undercut its credibility. Among these: an article suggesting that Minneapolis cop Derek Chauvin may have been wrongly convicted in the murder of George Floyd—a claim that prompted a devastating, multipart rebuttal by Radley Balko—and another making shaky assertions about skyrocketing crime under a progressive district attorney in Austin, Texas, also convincingly deconstructed by Balko in The Unpopulist.