George Shultz at 100

The economics professor who became secretary of state and won the Cold War.

In early November 1986, just days after the midterm elections, the biggest scandal of the Reagan presidency broke. In what would come to be known as the Iran-Contra affair, U.S. officials had sold arms to Iran in return for Iran’s cooperation to free American hostages in Lebanon, then illegally sent that money to anti-Marxist rebels in Nicaragua.

Journalists began to sink their teeth into the controversy, some speculating about whether the secretary of state should be fired or resign. George Shultz, who had been in the job for four years, had consistently opposed the arms-for-hostages scheme, but it went forward in secret without his knowledge. Now, following the coverage in the newspapers and on TV, he knew that the remaining months of the Reagan presidency could well be dominated by the biggest political crisis since Watergate.

“I knew my job was on the line,” Shultz recalled in his 1993 memoir, Turmoil and Triumph. “But proud as I was to be secretary of state and conscious as I was of possible achievements of great significance, I knew I could not want the job too much.”

As he was grappling with these questions of scandal and service, career and country, Shultz got a phone call. It was Charles Krauthammer. Shultz’s resignation, the columnist said, would be a disaster: “The wrong man always resigns in cases like this.”

Shultz stayed through the crisis—and through the end of the Reagan presidency. And he would deservedly be remembered among the greatest secretaries of state, one who deftly combined America’s economic and military might with its moral authority to win the Cold War.

George Pratt Shultz was born in midtown Manhattan on December 13, 1920—so this weekend he celebrates his hundredth birthday, a fitting occasion to look back at his life and career.

Shultz’s father had a Ph.D. in history from Columbia but had left academia to work on the New York Stock Exchange. Young George was raised to love books. At Princeton, where he had a tattoo of the school’s tiger mascot inked on his posterior, he studied economics and international affairs. He wrote his undergraduate thesis on the then-still-new Tennessee Valley Authority.

During Shultz’s senior year at Princeton, Japan attacked Pearl Harbor. Eager to join the war, he “tried to enlist in the Royal Canadian Air Force as a way of getting over there and doing my part,” he wrote in his memoir, “but my eyes weren’t good enough to pass their test.” Instead, he joined the U.S. Marine Corps, where he was commissioned a second lieutenant. “Take good care of this rifle,” his drill sergeant told him in boot camp. “It’s your best friend. And remember one thing: Never point it at anybody unless you’re willing to pull the trigger.” Serving as an artillery officer in the Pacific theater, he participated in the battles for two of the lower islands of Palau.

There were heavy casualties, and I lost friends. . . . I went in on one of the early waves and wound up for a while more or less directing traffic on the beach. Conditions were chaotic. Supplies were pouring in. The beach was crowded, so matériel had to be moved out to make room for more. As I worked to organize our beachhead, Japanese soldiers from the high ground fired down on us. That day I saw the savagery of war. When the Japanese snipers were finally talked into coming out with their hands up, they were hit by fire from all over the beach.

After returning from the war, Shultz went to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology for graduate studies in industrial economics. Because of the timing—he started in fall 1945, immediately after the war’s end—there were few other students. In a course with future Nobel laureate Paul Samuelson, Shultz had only one classmate. For one statistics course in which he was the only student, the professor held class peripatetically.

In 1946, Shultz married Helena “O’Bie” O’Brien, a military nurse he had met two years earlier when stationed in Hawaii. After finishing his Ph.D. in 1949, he stayed at MIT to teach. In 1955, the young academic briefly joined President Eisenhower’s Council of Economic Advisers. He then moved to the University of Chicago, not to the economics department—although he would befriend its future Nobel laureates George Stigler, who sold Shultz his dining-room furniture, and Milton Friedman—but as a professor in, and eventually dean of, the graduate school of business.

President Nixon, at the advice of a mutual friend, economist Arthur Burns, recruited Shultz to be his first secretary of labor, marking Shultz’s entry into top-tier politics. He would hold two other cabinet posts under Nixon: director of the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) and secretary of the treasury. In those capacities, he would privately negotiate desegregation of schools and the workforce and impose punitive policies against companies that discriminated in hiring black workers. In public, Nixon would call him “a man of exceptionally sound judgment” and among “the ablest members of my administration”; in private, Nixon referred to him as a “candy ass” for not deploying the IRS against Nixon’s enemies.

After leaving government, Shultz went to work for Bechtel, soon becoming president of the vast construction and engineering firm. (Among his colleagues there was Caspar Weinberger, who had been his deputy and then successor at OMB and would go on to be his colleague in Reagan’s cabinet.) While he was an economic adviser to Ronald Reagan’s 1980 campaign, he was initially passed over for a job in the administration. Writes Reagan biographer Lou Cannon, former President Nixon “was determined to keep [Shultz] from landing a high post in the Reagan administration.”

Shultz’s turn would come, though. Reagan’s first secretary of state, Al Haig—a Nixon favorite—was a retired four-star general in the U.S. Army, former Supreme Allied Commander Europe, chief of staff to both Nixon and Ford, and Henry Kissinger’s deputy at the National Security Council. However, his time as secretary of state was characterized by his rocky relationship with the White House. The most memorable moment of his tenure came after the assassination attempt on President Reagan, when Haig, in a bumbling attempt to project calm, infamously strode into the White House press briefing room and said “I am in control here.”

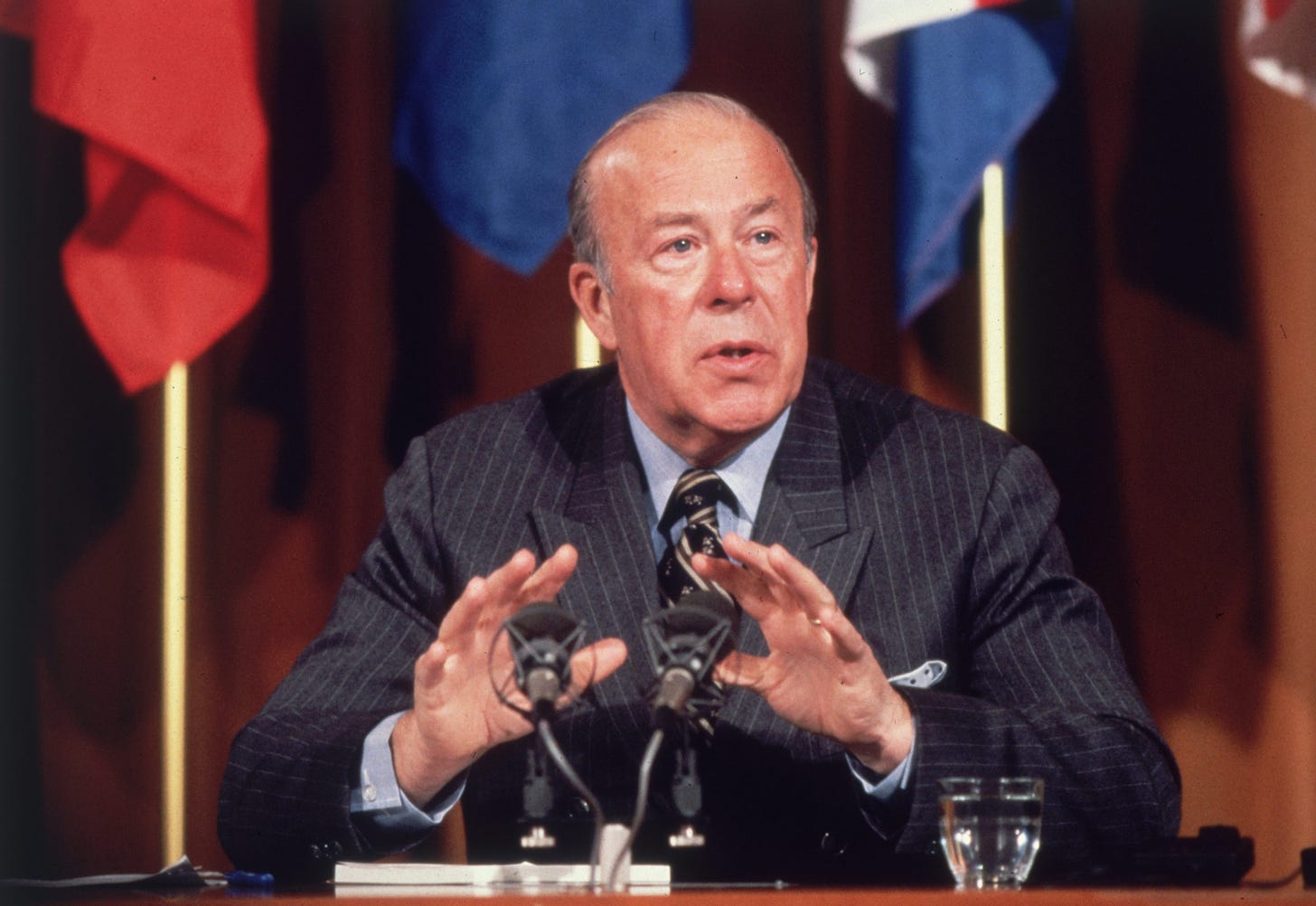

George Shultz, photographed in 1983. (Photo by Michael Evans, courtesy the Reagan Library)

George Shultz did not have Haig’s credentials. His highest military rank was captain. He was a university professor, a dean, and a businessman, not an experienced officer or diplomat. While he had served at a high level in the Nixon administration, his government work had been related to his area of academic expertise, economics. His experience in diplomacy and foreign affairs was mostly limited to negotiating trade deals, not arms control or human rights.

Yet Shultz benefited from those experiences. He had watched Henry Kissinger formulate strategy. As a labor negotiator, he had developed the necessary skills for negotiations. As a university administrator, he had to learn about bureaucracy. But what made him exceptionally well suited to the position of secretary of state—and certainly better suited than the tempestuous Haig—were his calm steadiness, high emotional intelligence, understanding of human nature, and capacity to manage a large government bureaucracy. His integrity would prove invaluable as well.

On June 25, 1982, President Reagan called Shultz, then on a business trip in London, to tell him that Haig had resigned and to invite him to become secretary of state. He said yes.

Unlike many of his predecessors and successors in the office of secretary of state, Shultz understood his mandate to be not the creation of policy but the execution of the president’s desired policy. To his assistants who would raise objections to Reagan’s policies, he would say, You know, you may be right. What you need to do is to get elected president. But since Ronald Reagan is president, we’re going to do what he wants to do. He would push the president in private and eventually had considerable success in changing Reagan’s mind on some matters, but he was not a self-aggrandizing secretary.

Not only did Shultz never cross the president, but his assistants revered Shultz too much to ever cross him. Talk to them today about him and they will mention to you his integrity, calling it “rare in Washington.” When, in 1983, President Reagan ordered lie-detector tests as part of a leak investigation, Shultz objected on his own behalf—“Mr. President, you’ll only polygraph me one time. And then you’ll get yourself another secretary of state”—and on behalf of his department. His support for his subordinates earned him their loyalty in return.

Too often, when Reagan devotees didn’t like a policy of his administration, they believed that the Gipper was being betrayed by his advisers, especially Shultz and James Baker. This concern would give rise to the slogan “Let Reagan Be Reagan!” Republican Congressman Jack Kemp called for him to resign at least twice. In 1984, Bob Novak and Rowland Evans claimed that he was purging Reaganites from the State Department: “With Shultz now in the close embrace of the Foreign Service, the president’s diplomacy is likely to be turned away from his own strong ideological convictions on the world struggle.” Ed Feulner, then president of the Heritage Foundation, charged that he was “a pragmatist” who wanted to “resolve problems”—coded language meaning that Shultz was a squish, a ridiculous charge on its face. And he never got along with some of the president’s right-wing political staffers, especially Pat Buchanan, whom he considered a “flamboyant right-wing hard-liner.”

What repeatedly helped Shultz was his integrity. The president never doubted his dedication. Frustrated with the administration’s ideologues, he twice tendered his resignation; both times it was rejected by the president. Reagan knew that Shultz was doing what he had ordered him. And Shultz benefited from the trust of the president’s closest adviser, Nancy Reagan.

President Ronald Reagan and Secretary of State George Shultz in 1988. (Bettmann / Getty)

One of the biggest intra-administration fights Shultz faced was with Jeane Kirkpatrick, the U.S. ambassador to the United Nations. Kirkpatrick was a Democrat who came on Ronald Reagan’s radar for her famous essay “Dictatorships and Double Standards.” She attacked the Carter administration for betraying America’s authoritarian allies and letting them fall in Iran and Nicaragua in the name of human rights. It was a doctrine that Reagan signed up for.

Shultz understood the problem with Carter’s policy, but he was not willing to abandon human rights. He needed to fight for the soul of the administration’s foreign policy. Early in his tenure, he ordered for the office of assistant secretary for human rights and humanitarian affairs to be renovated. The office was in poor condition and had been, physically and metaphorically, neglected under Haig. By ordering the renovation, he was signaling a change of course.

The change meant battling the White House to push out allied dictators against Kirkpatrick’s recommendation. The first battle came over the Philippine dictator Ferdinand Marcos, whom Reagan considered a friend and was reluctant to push out of power. Through Shultz’s persuasion and thanks to events, Reagan stopped backing Marcos, and soon he was out. South Korea was another country whose democratic transition Shultz facilitated.

No region was more important to Shultz than the Americas, and Latin America—then rife with military dictatorships, juntas, and revolutionary Communists—received extraordinary attention under Reagan and Shultz. Augusto Pinochet, a brutal military dictator who had stopped communism in Chile, had created a market economy with the advice of free-market economists in his cabinet. Yet when, at a National Security Council meeting, Reagan suggested inviting Pinochet to the White House, the normally mild-mannered Shultz raised his voice: “No! No! No! No!” There was no way that the Chilean butcher was going to get a photo op with the president of the United States. Even though he personally knew several members of Pinochet’s cabinet—some had been his students at the University of Chicago—he never rejected withholding aid or imposing economic pressure on Pinochet. By the time Reagan left office, he had lost a referendum and was on the verge of leaving office. In Nicaragua, although communist Sandinistas won initially, they would be kept out of office for over two decades thereafter. El Salvador became a democracy on Shultz’s watch, and so did Grenada after the U.S. invasion in 1983.

The Middle East is an outlier in Shultz’s tenure—it’s where he most badly came short. The United States negotiated but failed to implement the withdrawal of the Syrian military from Lebanon, especially after the U.S. military left the country following the 1983 bombing of the Marine barracks in Beirut. His Israeli-Arab-Palestinian peace negotiations did not get anywhere. And he was undermined by the officials who engineered the arms-for-hostages arrangement with Iran, a policy he vehemently objected to, which almost ended Reagan’s presidency.

Shultz’s greatest success, however, is the end of the Cold War. Unlike Haig, who clashed with Reagan over the fundamental stance toward the Soviets, Shultz found ways to work within Reagan’s policy preferences while also slowly changing Reagan’s mind. He adopted a dual-track strategy to negotiate arms control with the Soviets: The United States would strengthen its nuclear capabilities in Europe to put pressure on the Soviet Union while negotiating arms reduction. That, combined with Reagan’s Strategic Defense Initiative and conventional military buildup, forced the Soviet Union to ramp up its own military expenditure. When reformers Mikhail Gorbachev and Eduard Shevardnadze rose to power, he seized the opportunity to work with them. Were Reagan and Shultz, and their successors George H.W. Bush and James Baker, lucky that their tenures coincided with that of Mikhail Gorbachev, a sincere reformer in good faith? Yes. But they made their own luck. It was, in part, their pressure on the Soviet Union that forced the Communist Party of the Soviet Union to elevate a reformer to the position of general secretary.

Shultz’s pressure on the Soviet Union was not just military and economic, combined with tough negotiations—it also involved human rights. He provided strong support for Solidarity in Poland. He was a stalwart advocate for Soviet Jews. In fact, no American statesman, other than Senator Henry Jackson, advocated for Soviet Jewry as much as Shultz did. He successfully advocated for their right to migration and Natan Sharansky’s release from the gulag. In a symbolic and important gesture, to advocate for their right to worship he invited Soviet Jews to the U.S. embassy in Moscow for a seder dinner, which he attended, telling the guests, “Never give up.”

Shultz’s greatest strength was his trust in America’s values. It is expected of states to advocate for their immaterial values in foreign policy. What he understood was that American values are not a liability but a strength. He never shied away from using America’s economic strength and military might to promote the country’s core values. He understood that the Cold War was not just a standoff between two superpowers but also a struggle for freedom. And where freedom expanded, Soviet power contracted. America could only win the fight for a free world if it held allies and enemies to the same standard. Shultz compared diplomacy with gardening, meeting leaders at their own homes, where they are most comfortable. America has made the world a beautiful garden—but without constant gardening it can turn into a jungle.

George P. Shultz’s tenure as secretary of state was longer than all but a handful of the other 67 men and women to serve in the job. And he is one of only five people ever to serve as both secretary of the treasury and secretary of state.

Shultz has a longstanding affiliation with Stanford’s Hoover Institution, which has set up a special website to mark his hundredth birthday. He remains involved in watching international affairs—in fact, he is the coauthor, with a Hoover colleague, of a book on world affairs published just last month.

“A good family life,” Shultz says, “is the building block of society.” His five children, eleven grandchildren, and seven (so far) great-grandchildren are a testament to his life well lived.

Of Washington, Shultz once said “Nothing ever gets settled in this town. . . . It’s not like running a company or even a university. It’s a seething debating society in which the debate never stops, in which people never give up, including me.” Looking back from the vantage of three decades after he left office, historians can judge that he was on the right side of those debates. As the United States returns to great power competition, foreign policy practitioners will be wise to study his career and his balanced, principled mode of leadership.