The Glamour Shots That Defined Golden Age Hollywood

George Hurrell’s era-defining masterpieces of shadow and light.

Star Power: Photographs from Hollywood’s Golden Age by George Hurrell

National Portrait Gallery, Washington, D.C.

through January 5, 2025

“WE DIDN’T NEED DIALOGUE. We had faces!” So declared silent film star Norma Desmond, played unforgettably by Gloria Swanson, as she remembered her past glory in Billy Wilder’s Sunset Boulevard (1950). Desmond was right, but what made those Hollywood faces dazzle was a portrait artist who suffused them with the magic of star power.

Photographer George Hurrell (1904–1992) was the quintessential creator of iconic star images in the heyday of the Hollywood studio system. Hurrell’s 8-by-10 black-and-white photographs erased any whisper of everyday humanity. Instead, he used his camera to sculpt stellar images that radiated superhuman qualities of glamour and allure.

The National Portrait Gallery has opened a riveting exhibition on Hurrell’s Hollywood glamour photography. Star Power was organized by Ann Shumard, the gallery’s senior curator of photographs, who describes how the timeless Hurrell images “helped define the public personas” of some of the “most glamorous figures” of Hollywood’s first Golden Age (from the 1920s to the late 1950s). There are twenty-two photos on display, including twenty from a new acquisition of seventy Hurrell photographs.

Born in Ohio, Hurrell studied painting at the Art Institute of Chicago. He used photographs to document his art, and earned money working part-time in the photography studio of Eugene Hutchinson, a noted portraitist. In 1925, Hurrell left Chicago’s brutal winters for the warmth of Los Angeles, where he set up a small studio in a neighborhood of lofts and galleries. He soon abandoned painting because the “slow pace got me,” and focused solely on photography. Studying the photographs in Vogue and Vanity Fair, he was especially impressed with those of Edward Steichen, the chief photographer at Condé Nast publications. When Steichen came to Hollywood in 1928 to photograph Greta Garbo and John Gilbert for Vanity Fair, Hurrell offered him the use of his darkroom. Hurrell considered Steichen “the great commercial photographer,” and was thrilled when his idol advised him that he should “always be the master of the situation.”

The next step in Hurrell’s Hollywood journey came when he photographed local society figure Florence “Pancho” Barnes.1 Wowed by photographs that made her seem glamorous, Barnes then convinced her friend, silent film star Ramon Novarro, to have his picture taken by Hurrell. The young photographer’s studio was tiny and lacked many accoutrements like “props” used by better established photographers, but the lack of extras worked well with Hurrell’s own sense that lighting was the key to movie portrait photography. He used light and shadow to sculpt Novarro’s features into something magical.

Novarro was so impressed that he took his photos to MGM’s publicity department, which was also delighted with Hurrell’s work. The studio asked him to photograph Norma Shearer, a top box office star who was married to MGM Head of Production Irving Thalberg. His Shearer photos were such a success that MGM hired him as their chief portrait photographer.

Hurrell quickly transformed studio photography into a major player in the star-making process. During the silent movie era, photographs of stars had mimicked theater photography, which often depicted stage actors in costumes and poses related to their most famous roles. In the teens and twenties, Hollywood studios copied such pro forma star-marketing devices, churning out steady streams of unexceptional photographs to meet the demand of fans and fan magazines.

But Hurrell changed the assembly line production of star photography. He created unique and iconic images that “branded” a star personality in the public mind. He used photographic closeups and relied on dramatic lighting to convey the glamorous allure of a star’s personality. His image-making was so significant that it was often the Hurrell image more than any particular movie that defined a star’s public persona.

Lighting was the key to Hurrell’s photography, and he used spotlights, soft focus, and a boom light that could be moved until it gave him exactly the “look” he wanted. He asked his subjects to pose for him without the heavy makeup used for motion picture cameras, and they trusted him when he said he would retouch any imperfections. Major star Joan Crawford, who had a faceful of freckles without makeup, became one of Hurrell’s biggest fans when she saw how glamorous her retouched photographs looked.

THE OVERSIZED HURRELL IMAGE that beckons visitors into the Star Power exhibition features Jean Harlow draped across a polar bear rug. Known as Hollywood’s original “Blonde Bombshell,” Harlow was cast by MGM in films that showcased her comic expertise along with her sex appeal, including Red Dust (1932) with a pre-mustachioed Clark Gable, and Dinner at Eight (1933), where her innocent greeting to hostess Marie Dressler sparks one of the classic double-takes in all film history.

Among the transfixing images in the exhibition is Hurrell’s double portrait of Gable and Crawford, originally shot as a publicity photo promoting their 1936 film Love on the Run. Gable had become a top male star after his Oscar-winning performance in It Happened One Night (1934), while Crawford’s path began in the silent era. She was a chorus girl in a Broadway revue when MGM signed her to a contract in 1925, and became a star while dancing the Charleston in Our Dancing Daughters (1928). She then made a successful transfer to “talkies” and starred with Hollywood’s top leading men throughout the 1930s.

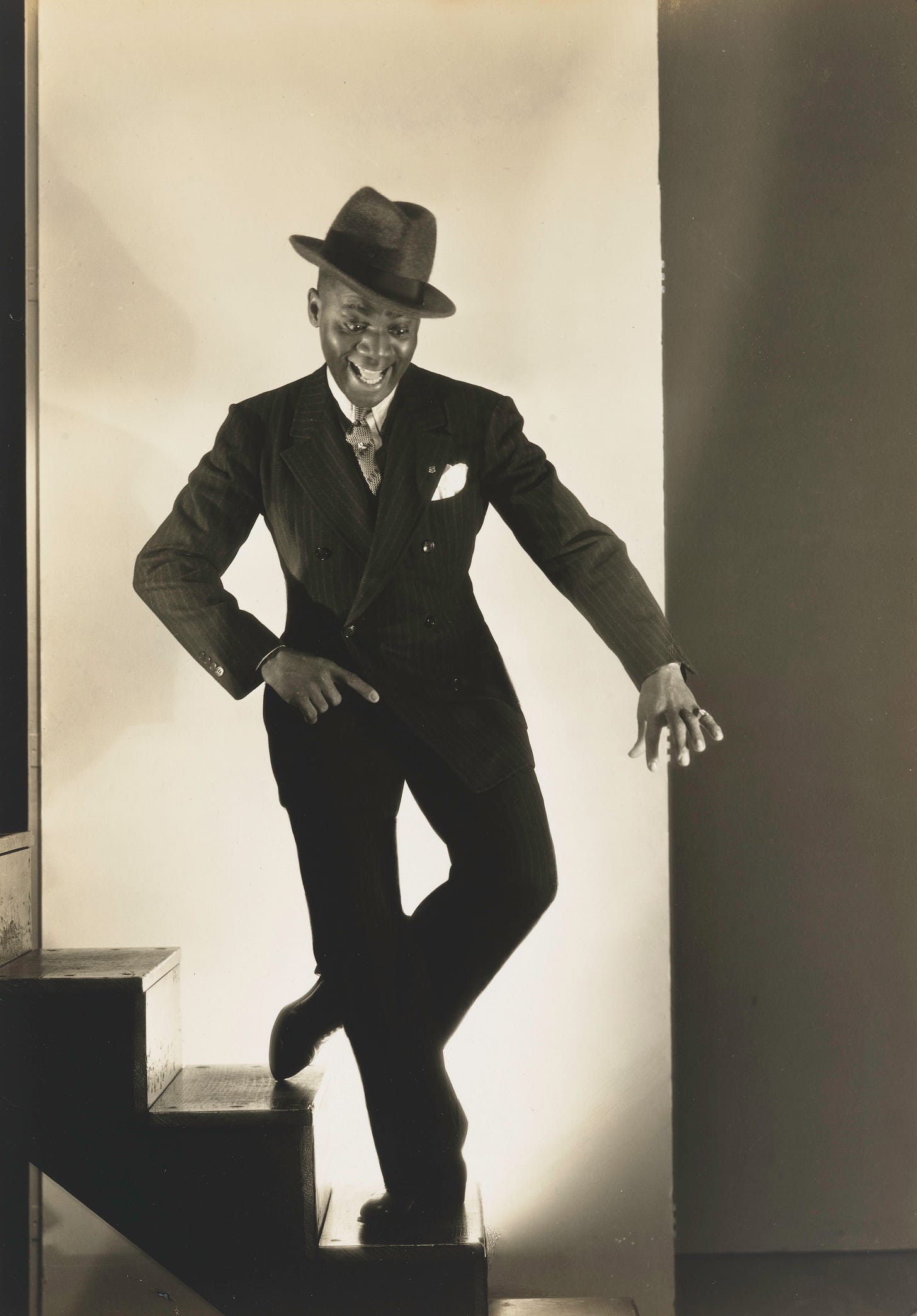

Visitors will see a dramatic photograph of Bill “Bojangles” Robinson, a virtuoso of stage and screen tap dancing. Robinson was the first black solo performer on the Orpheum vaudeville circuit from 1914 to 1927, then won fame on Broadway with the all-black revue Blackbirds of 1928. In the 1930s, while Hollywood’s studio system remained as segregated as America at large, Robinson earned wide renown for the four movies he made with child star Shirley Temple. Their most memorable scene was the stair dance they performed in The Little Colonel (1935).

Another alluring exhibition photograph is that of dapper William Powell. The six “Thin Man” murder mysteries he filmed with Myrna Loy made him a top box office draw—Depression audiences cheered his portrayal of the martini-drinking detective Nick Charles, and adored Loy as his clever and infinitely patient wife Nora.

The Portrait Gallery’s sampling of Hurrell’s glamour photographs, which date from the period between 1930 and 1942, gives us a sense of why movies flourished in the Depression. When money was tight and soup lines were long, why would 60 to 80 million people every week spend a quarter on something as frivolous as a movie?

Why? Because movies offered an escape. Hollywood’s Golden Age created worlds removed from reality’s drab darkness. The glamour and allure of George Hurrell’s faces were not what we saw everyday in the mirror. Instead, his portraits illuminated extraordinary faces that were always ready for their closeups.

Admirers of Tom Wolfe’s book The Right Stuff or Philip Kaufman’s movie adaptation will remember Pancho Barnes as the proprietor of the club in the Mojave desert where the test pilots liked to hang out.