God Talk

David Bentley Hart’s exploration of our deepest and oldest questions rehabilitates a form that modern thinkers typically avoid: the philosophical dialogue.

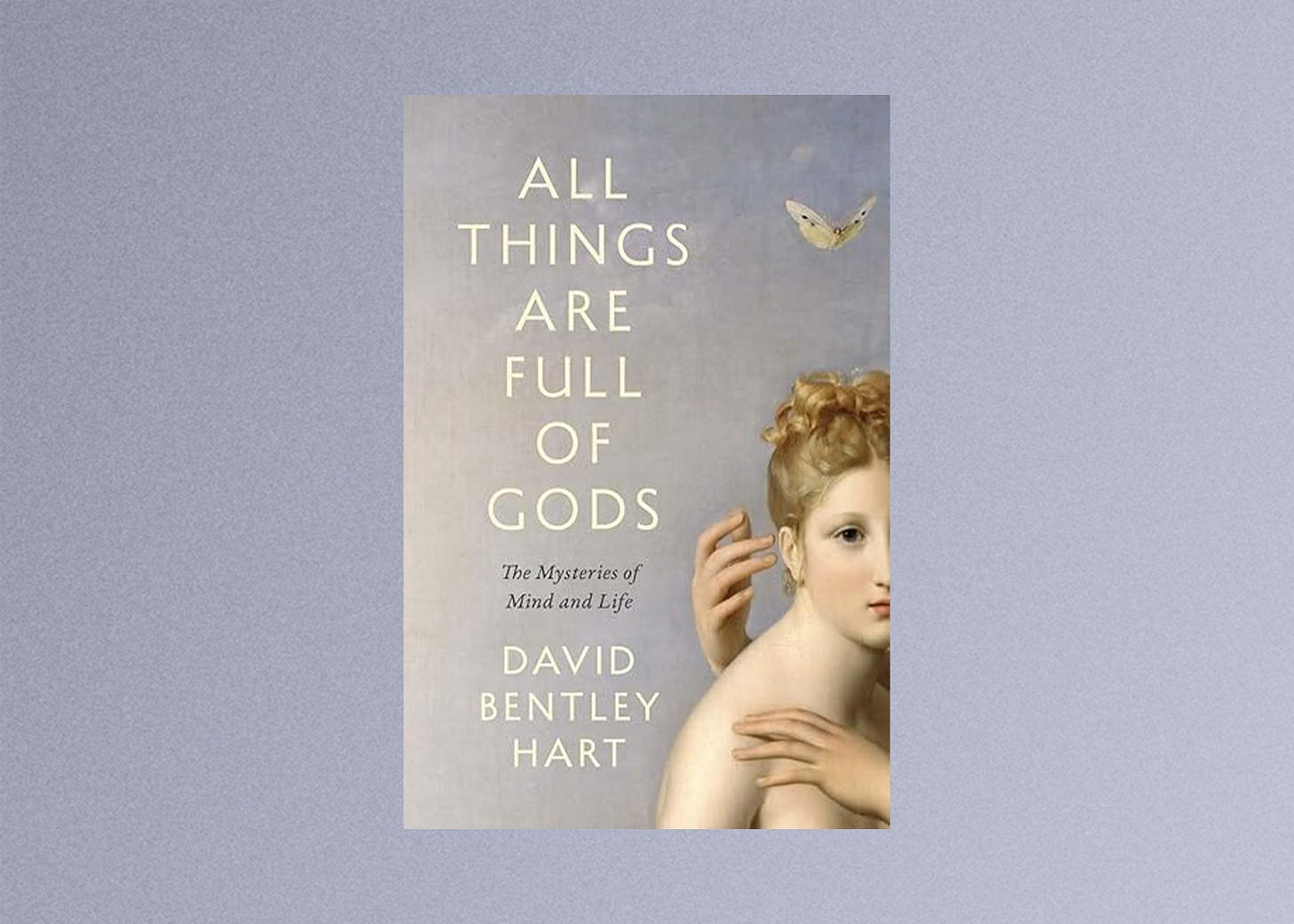

All Things Are Full of Gods

The Mysteries of Mind and Life

by David Bentley Hart

Yale, 528 pp., $32.50

WHAT FORM SHOULD PHILOSOPHY be written in? Since early modernity, the presumed answer has been the argumentative philosophical essay, which makes a definite claim, marshals arguments for that claim, and contends with anticipated counterarguments under the voice and identity of the author. It presumes a certain earnestness and transparency; its written exemplar is the scholarly article submitted for circulation and criticism by one’s peers, and its living exemplar is the man standing at Speaker’s Corner in Hyde Park, holding forth on his views and taking on all challengers.

Philosopher-theologian David Bentley Hart is no stranger to this style; indeed, most of his work has embodied the essay (or the monograph) at its most vigorous and vituperative. He is sincere in his commitments and happy to be criticized for what he believes, reserving his sharpest polemics for critics who ascribe to him views that he does not profess or who similarly abuse historical thinkers who are no longer around to defend themselves. But there is another approach to writing philosophy, a form at once more venerable than the essay and far more difficult to write well, and it is this form that Hart has adopted to produce All Things Are Full of Gods.

The philosophical dialogue did not spring fully formed from Plato’s stylus, but he was its first exponent, and within his own lifetime he brought it to perfection through the so-called “middle dialogues”—such legendary texts as the Republic, Symposium, and Phaedrus. These are masterpieces of such overwhelming intellectual and artistic force that in reading them, one feels that the greatest questions of life cannot be approached otherwise.

The dialogic form flourished throughout antiquity and the medieval period, becoming the center of intellectual life off the page in the form of the Scholastic disputatio, wherein theoretical points were settled in the course of rigorous communal debates. As late as the seventeenth century, important works such as Galileo’s Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems continued to reflect a still-living tradition that held conversation to be the only way to establish the truth.

Hart has ventured into the dialogic tradition in the past—most notably with Roland in Moonlight, a weird and delightful book of conversations between the author and Roland, his dog. In the present volume, Hart has shifted from the living room to Mount Olympus and replaced his furry companion with a cast of Greek divinities. We encounter them at the beginning of an exchange of leisured musings on the subject of mind; their primary concern is whether it is reducible to matter. Hart makes his aim clear from the outset: However whimsical its conceit, this book is a polemic against materialism, and it deploys every resource available to make its case.

I WILL SAY AT THE OUTSET THAT Roland in Moonlight is much the more enjoyable read. In purely literary-technical terms, Roland’s voice as rendered by Hart has far more personality, humor, and wisdom than Hart is able to give the Olympian and Olympus-adjacent interlocutors of All Things Are Full of Gods. Hart, for his part, would probably say that this he is merely a faithful recorder, and that it would be foolish to expect from mere deities the depth of thought and greatness of soul found in dogs. (To anyone who has known a dog well, this is so obvious that it defies demonstration.1)

The dialogi personae are four deities familiar to anyone likely to consider picking up this book: Eros, the god of love; his divinized human wife, Psyche, whose name means Soul or Mind; the messenger Hermes, who mediates between gods and men and between life and death; and the smith-god Hephaestus, peerless shaper of matter and said to be able to craft machines that moved on their own power.

This last divinity is the main advocate here for materialism, and it is to Hart’s credit that Hephaestus is reasonable, intelligent, and well read. The problem he poses to his companions is, after all, a worthwhile and complicated one: How is it, precisely, that this thing called “mind” or “consciousness” arises in animals that are, under scientific analysis, reducible to a series of working parts, electrical signals, and, ultimately, atomic interactions?

Psyche: Do you see this flower, my love?

Eros: Of course, my soul, very clearly.

Psyche: I plucked it just now from the rose tree at the center of our courtyard.

Eros: So I guessed.

Psyche: [Addressing all three:] And yet I didn’t do so impulsively. I was detained for some time by my own indecision. I happened to note this one blossom among all the others, and was drawn to its singular perfection and beauty, but I deliberated for some time before breaking it from its branch. On the one hand, I found its loveliness too delicious to resist; on the other, I wasn’t entirely sure that I cared to remove it from its natural place, where it shone out to such exquisite effect amid that inordinate, gorgeous pattern of blossoms and leaves.

Thus Psyche begins the dialogue. What fascinates her is not the rose in se but her own unified process of perception, intention, deliberation, and selection. What happens as she sees the roses, sees this rose, and then weighs one decision among many, weighing possible futures, possible visions, until she finally comes to a decision and makes it? Obviously, something is happening; indeed, quite a lot of identifiable processes are going on, but those processes are also interlocked and ordered so that they form a seamless whole of experience, a single interior life. This is the problem to which, pace the smith-god, materialism has no answer.

The answer that the other three interlocutors put forward in response to this problem is that mind is simply not reducible to material processes: It is something prior to and distinct from matter. Pictures of nature that take this into account are not only more beautiful and satisfying but more complete and more accurately descriptive than those that do not.

Most notable among the positions Hart attacks is the popular modern view that the impersonal “third-person” description of reality touches what is truly real, and all other modes of description—but especially the interior and “first-person” mode—can show only what is emergent from, parasitic upon, or derivative of the impersonal “external” reality. Hart contends that this gets things exactly reversed: “Third-person” is the muddying abstraction because the consciousness of the one describing is always prior, assumed, even suppressed. There is no description without a descriptor, after all; there is no abstraction without a mind to do the abstracting. A world wholly independent of interior experience can only be speculatively posited in the context of the mediating, wholly self-referential world of language, where we encounter other minds and can regale them with imaginings of nearly anything, possible or actual—even something as ridiculous as a “third-person” reality in which mind plays no role.

The case, taken in full, is persuasive, and each interlocutor has his or her role. Psyche is, of course, a stand-in for us: a human being, but an elevated one, for here Soul has been united with Eros, and in being drawn up, she becomes something divine. She is the dialogue’s primary exponent. Eros is here to show that mind is not static but actively reaches out to the world and to other minds. It is eros that pulls us into the interiority of another person, and as Plato first taught us, it is the soul impelled by eros that is drawn most strongly toward wisdom.

Hermes stays out of the dialogue at first, but he takes it up in earnest when the subject turns toward language:

Hermes: The effect of intention on sensory data is interesting, no doubt, but surely the most conspicuous expression of intentionality of all is language. Yes, we interpret everything. We see a plume of smoke as a sign of fire. We see an expression crossing the face of a friend as indicative of displeasure. But in these instances it’s easy to mistake what we’re doing for something continuous with a mere system of stimulus and response. It’s only in the full range of our semeiotic capacities that we see the obvious difference between intentionality and anything reducible to the physical interactions of our neurology with our environment. Language is nothing but intentionality, purposive meaning communicated in signs. It’s a world alongside the world, so to speak, or a plane of reality continuously hovering above the physical plane, a place in which meaning is generated and shared entirely by meaning.

You’ve probably already started to get the sense, however, that although the roles of these divine personages are distinct, their voices are less so. The following is a gloss from Psyche on intention, but any reader of Hart’s other books will likely hear a familiar voice:

Part of the mystery of the mind is that, in order to know or experience anything, it must already “will” to do so; but, in order to will something, it must somehow know what it’s willing. We don’t merely receive the world mentally; we must in a sense go out in search of it, though we may not be consciously choosing to do so; and that’s possible only because we know what we’re seeking, even if only in a very general way. This mysterious inseparability of knowing and willing is intentionality. Really the mystery here is all rather elegantly comprised in the Latin term intentio—an act of being directed to or of reaching out toward some end. Already, in putting the matter that way, we find ourselves confronted with a phenomenon that seems to defy the mechanical philosophy’s deepest principles; there’s no more conspicuous example of teleology in nature—of final causality, or antecedent finality, or intrinsic purposiveness, or whatever you choose to call it—than the directedness of mind and will toward an end. This is the diametric opposite of the mechanistic understanding of nature. Nor is this a rare or marginal phenomenon; arguably it’s necessarily present in every conscious state. Each act of thought and volition, of perception and judgment, even of simple recognition is dependent upon this initial going-forth of the mind toward the world.

This and the other excerpts provide a representative sample. The name and identity may here be those of a mythological woman, but the tone and cadence are Hart’s through and through. What’s more, his deities have done a great deal of reading in contemporary philosophy of language and mind, and they cite their sources by name. That is not a bad thing in itself, but it does mean the locus of interest is the subject matter rather than the artistic execution.

HERE WE SEE, PERHAPS, WHY the dialogue fell out of favor: It is hard to do well. The form demands both the intellectual sharpness and vision to see a question clearly and the dramatist’s gift for characterization, variation, and voice. No one since Plato has possessed both in such great measures as he did. Hart lacks the true gift of the dramatist and does not pretend to it, but he supplements his prodigious intellect with a good appreciation for form, with good taste, and with his own irreducible personality. These certainly do not make him the equal of Plato, but they do make his tour of philosophy of mind a real pleasure for anyone who maintains an interest in our deepest and oldest questions.

Does All Things Are Full of Gods vindicate the dialogue as a form? Should contemporary philosophers abandon their dry and impersonal discourses and start writing this way instead? Probably not—the essay really is easier to do well, and reading a bad essay is more bearable and less personally offensive than being subjected to bad drama. Most of us who try our hands at philosophy are conformists and mediocrities. Better to leave philosophical drama to those brilliant visionaries and intractable cranks who constantly threaten to rip the bars off the essay and loose themselves upon the reader; in the dialogue they can find a sturdier container for their empyrean songs and barbaric yawps. Hart is certainly one of this number; whether he is a seer or a crank can be settled only by reading him.

My mother’s older dog, deceased as of May, was the most pragmatic and savvy animal—of any species—that I have ever known. Her younger dog, a creamy-white golden retriever of astonishing beauty, remembers well the days when she was small enough to curl up into my lap as a puppy; whenever we reunite, she tries to demonstrate that this is still a perfectly feasible arrangement, and that only my restricted ambition and poor understanding of higher-dimensional physics stand in the way of reproducing it.