GOP Senators’ Bogus Arguments Against Trying and Convicting Trump

Precedent and prudence are not on their side.

The vote by 45 Senate Republicans on Tuesday to dodge the question of whether spending two months whipping your followers into a frenzy by telling outrageous lies attacking the foundation of our democracy and then turning them loose on the U.S. Capitol to shut down the electoral vote count amounts to an impeachable offense was not their finest moment. Whether it was their worst depends on how they vote when the trial concludes.

Few of the current crop of Senate Republicans are known for their courage, but this was a particularly embarrassing display. Rather than address the weight of the historical, prudential, and legal arguments on impeaching a former officeholder, they chose to tell themselves constitutional just-so stories that got them to a predetermined—and immensely convenient—conclusion. In fact, impeaching the now ex-president is almost certainly constitutional and it’s shameful that only five Republican senators had the courage to say so.

First, there’s the weight of historical precedent. In 1876 the Senate faced a similar question—it was actually a tougher case than the present impeachment—and concluded that Congress had the authority to impeach officials after they had left office.

Second, there is the prudential argument. Does anyone think it likely that the Founders intended to specifically exempt lame duck presidents from impeachment? Does it make any sense at all to allow Congress to bar sitting presidents from future office based on horrific acts in the first month of their terms but not for acts committed in the last month?

I don’t think there is any question that that is not what the Founders intended. Nor is there any question that it is an extraordinarily bad idea. If you put that interpretation of the impeachment power together with the idea of a presidential self-pardon—and there is a much better constitutional case for that than there is for not impeaching ex-presidents—you turn the Constitution into a demagogue’s charter. Lose the election? No problem! Call out those mobs and give it your best shot. It’s all good!

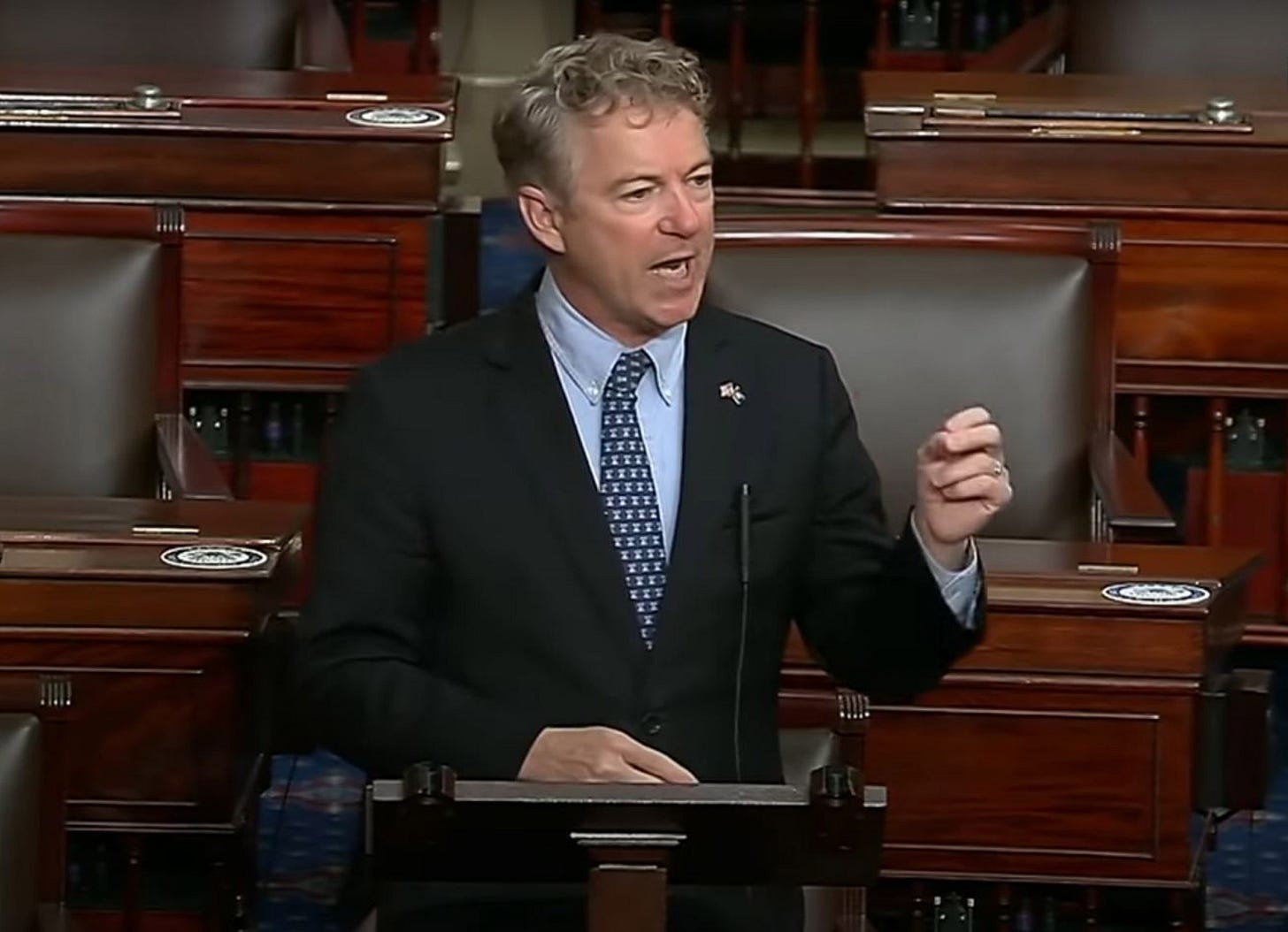

Finally, there is the legal argument. Republicans claim, as Rand Paul did on the Senate floor and in an opinion article on Tuesday, that it isn’t constitutional to impeach someone once he or she is out of office. Though the weight of precedent and logic say otherwise, fine, let’s assume that’s correct. Happily, that’s not what happened. Donald Trump was still very much in office when he was impeached—which is a formal vote by the House to adopt articles of impeachment—so there is no question that proceeding with the impeachment trial itself is perfectly constitutional.

Analytically, there are two separate concepts at play here, jurisdiction and mootness. In the 1876 case, Secretary of War William Belknap hurriedly resigned before his impeachment could be voted on in the House. When the Senate received the articles of impeachment, it took its own vote on whether it had jurisdiction to proceed with the trial and concluded that it did. Unfortunately for Belknap—and current Senate Republicans—“You can’t fire me. I quit!” isn’t actually a legal doctrine.

The current case isn’t even that close. The House impeached the now ex-president a week before he left office. If you want to analogize it to a court proceeding, there is no question that this case was brought before the statute of limitations expired. Once the court’s—in this case, the Senate’s—jurisdiction has attached, jurisdiction doesn’t “expire” no matter how long it takes to complete the trial.

Mootness is a different concept. When a court with proper jurisdiction can no longer offer a meaningful remedy, a case can be dismissed as moot. When Republicans say that the Senate doesn’t have the constitutional authority to hold an impeachment trial once a president has left office, what they are actually arguing is that the case is moot because an ex-president can’t be removed from office on conviction.

But again, that’s simply wrong. The Constitution provides two possible penalties for conviction in an impeachment trial: removal from office and being barred from future office. If an ex-president can be barred from holding future public office on conviction, there is still a reason to hold the trial and the proceeding is, by definition, not moot.

In a sense, this is now water under the bridge since the Senate has voted 55-45 that it does have jurisdiction to try this impeachment. If the senators honor their oath, they will now move on and consider whether Trump's efforts to overturn the results of an American election, efforts that ended in mob violence, are acceptable presidential behavior or whether they amount to an impeachable offense.

Unfortunately, a lot of Republican senators aren’t going to do that. They will vote not to convict and claim that they are doing it only because they don’t believe the trial is constitutional. That isn’t, of course, relevant to the question they are duty-bound to consider and it’s as gross a violation of their oath as refusing to convict because Chuck Schumer won’t promise to protect the filibuster.

It’s also a serious violation of the separation of powers. The Senate, as a body, has ruled that it has jurisdiction. If the Senate is wrong, that’s up to the judicial branch to decide, not individual senators. And the way that happens is for a convicted ex-president to challenge the Senate’s verdict in court. That’s the way our system is designed to work.

There is no fig leaf for Republicans here. They cannot hide behind pretend concerns about constitutional rectitude. The trial moves on now and if they vote to acquit, it’s either because they find Trump’s behavior acceptable or because they are terrified of his supporters and will do anything to please them. Pretending otherwise isn’t going to fool anyone—not the American people, not Donald Trump, and, most certainly, not history.