Guy Davenport’s Book of Everything

With ‘The Geography of the Imagination,’ the great critic invited his readers into a world of forever-expanding meanings, resonances—and joy.

The Geography of the Imagination

Forty Essays

by Guy Davenport

Nonpareil, 592 pp., $22.95

1981. MTV, THE SPACE SHUTTLE, AN EXPLOSION in the personal computing market. The People’s Republic of China welcomed its first Coca-Cola plant and its first American arms deals, the New York Native ran the first news story about the disease that would eventually be called AIDS, and a former labor leader and sometime actor was sworn in as president of the United States. The public library of Jaffna, Sri Lanka—one of the largest in Asia—was burned to the ground by a Sinhalese mob with the cooperation of local police. Guernica finally arrived in Madrid, in accordance with its creator’s wishes that it not come to Spain until democracy had. Albert Speer died—having lived as a free man for fifteen years—as did Jacques Lacan, Will Durant, and Hoagy Carmichael. Midnight’s Children, What We Talk About When We Talk About Love, and Simulacres et Simulation were published. Helen DeWitt was studying at Oxford, David Foster Wallace matriculated at Amherst, Anne Carson received a Ph.D. from Toronto, and the uncredentialed Chilean expat Roberto Bolaño was in Catalonia, writing the earliest of his published novels.

Somewhere in there, an irritable professor of English at the University of Kentucky had himself an annus mirabilis. In 1981, his fifty-fourth year, Guy Davenport published four books: two story collections, a translation of ancient Greek drama (The Mimes of Herondas), and a sage green compilation of forty essays titled The Geography of the Imagination.1 It is this latter volume more than anything that turned his name into a kind of password. I have made several friends, online and off, by discovering a shared devotion to it. If you know Davenport, you know Geography, and if you know it, you revere it.

Why the reverence? Have a look at the opening sentence of the book’s first and titular essay:

The difference between the Parthenon and the World Trade Center, between a French wine glass and a German beer mug, between Bach and John Philip Sousa, between Sophocles and Shakespeare, between a bicycle and a horse, though explicable by historical moment, necessity, and destiny, is before all a difference of imagination.

Even now, the brains of certain readers may be set to jangling and flashing like a pinball machine. Practically the whole of Davenport is contained here, as it is in most of his other sentences—he is the most pleasingly fractal of writers. Here is one of his favorite devices (the list), one of his standard modes (gnomic), his interest in form, his breadth of reference, his fundamentally apolitical approach.

The range of this particular sentence gives some idea why it is hard to summarize his work. He is interested in—what, culture? The things people make, how they make them, the myriad ways people extract meaning from the material stuff of the world, and the ways they attempt to inscribe meaning back onto it—most obviously art and literature, but technology, religion, and table manners, too. If we let him, Davenport will give us another word for this nexus: imagination, which for him is not creation ex nihilo but a furnace for smelting raw sensation, a means of interpretation and discovery, and the starting point of all art, all culture. “To trace its ways,” he says in the same essay, “we need to reeducate our eyes.”

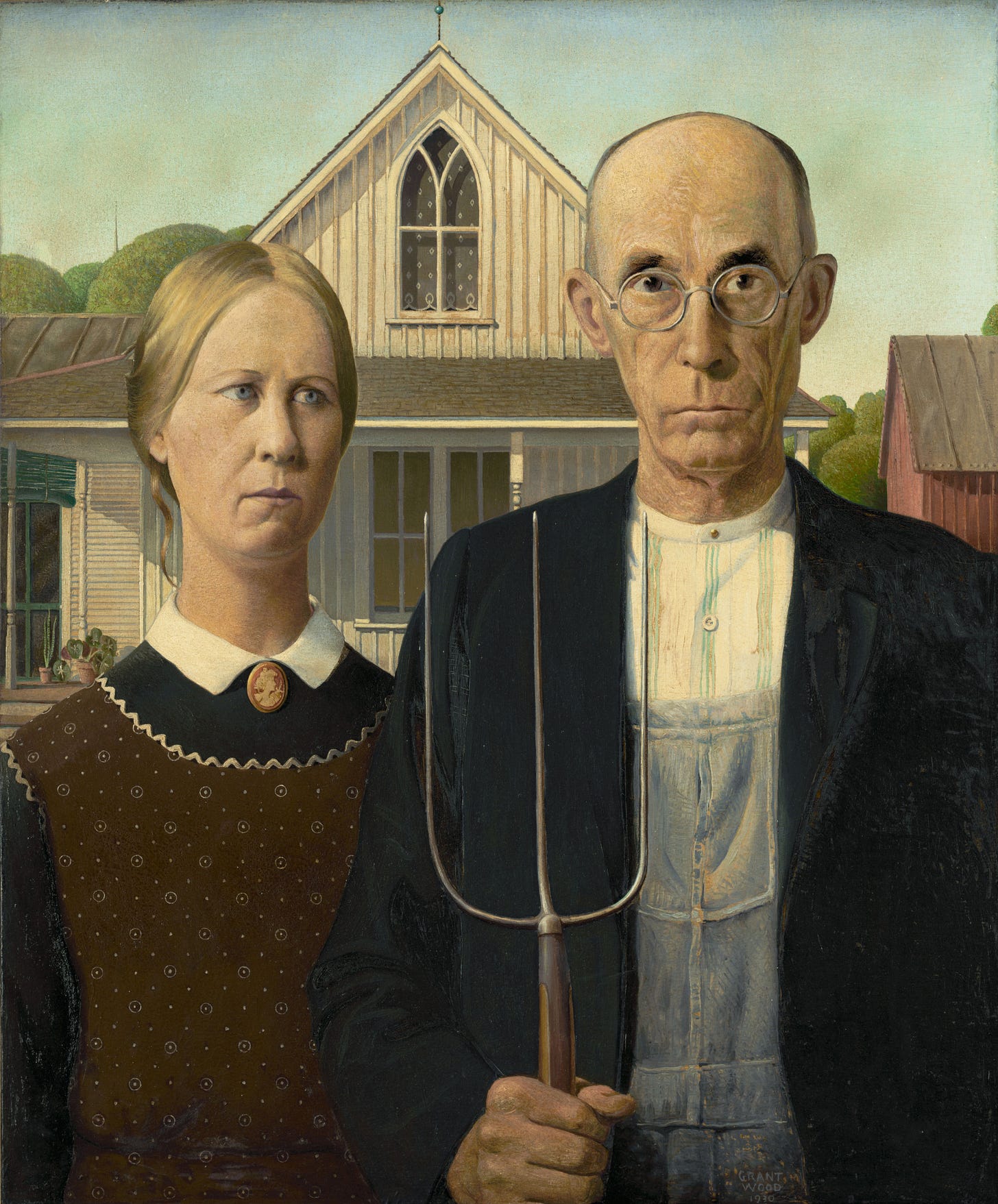

To commence our reeducation (still in that first essay), he takes Grant Wood’s American Gothic—a painting everybody knows and therefore nobody sees—and explicates practically every square inch of it, unveiling the material and cultural background of each detail, starting with “the Gothic spire of a country church, as if to seal the Protestant sobriety and industry of the subjects.” The spire? There’s no church in—oh, there it is. We are in very good hands here.

On towards the foreground, past the trees—“seven of them, as along the porch of Solomon’s temple”2—stopping for a good look at the house—“a bamboo sunscreen—out of China by way of Sears Roebuck—that rolls up like a sail: nautical technology applied to the prairie”—and the clothes of the subjects, which occasion brief histories of spectacles, denim overalls, the sport coat, buttons and buttonholes, and the cameo brooch. From these, Davenport extrapolates a whole economic world: “curtains and aprons are as old as civilization itself, but their presence here in Iowa implies a cotton mill, a dye works, a roller press that prints calico, and a wholesale-retail distribution system involving a post office, a train, its tracks, and, in short, the Industrial Revolution.” Reading this, my mind’s eye zooms out from the painting to a blank U.S. map where, as in an educational cartoon, each of these things sprouts up across the country as Davenport names them.

Regarding the farmer and his wife3 (“Martin Luther put her a step behind her husband; John Knox squared her shoulders; the stock-market crash of 1929 put that look in her eyes”), Davenport points out their pose is “dictated by the Brownie box camera” but is consonant with several millennia of marriage portraiture, from the Egyptians to Rubens. And so on4—by the time he is done, we are looking at an altogether different painting, and have gotten a crash course in Western civilization, too. Davenport’s associative catalogue amounts to far more than the dutiful squib of context a more pedestrian writer would provide while guiding the reader to some deeper, settled meaning. He argues his open-ended gloss is the meaning of the painting—what it invites us to see and think about. Davenport’s essay amounts to a restoration: Far from murdering to dissect, he has made American Gothic come entirely alive, and in a way that beckons us to continue thinking, exploring, imagining.

I HAVE LINGERED ON THIS READING of Wood’s painting because it is delightful and astonishing, but also because it is typical. Davenport’s essays are studded with such epiphanies. To read him is to start to see a world saturated with meaning, flaming out like shining from shook foil. Nothing is too trivial for him; he is a great collector of anecdote and colorful detail. If you are the sort of person who likes knowing that Shelley was six feet tall, that Spinoza mistook tulip bulbs for tasteless onions, that the great paintings of the Lascaux cave were discovered by a dog named Robot, that (can it really be?) Saarinen’s arch in St. Louis was originally designed for Red Square, then Geography is the book for you. Here is Whitman’s house in Camden, “shin-deep in wadded paper.” Here are brass bands playing the popular waltzes of the day amid the smoke and roar of cannon at Gettysburg. Here are the Wright brothers testing their flyer on a Monday—they were ready the day before, but would not break the Sabbath.

Sometimes I think of writers with this kind of bias for the granular as the “fantastic facts” school,5 and I nurse a fear that such criticism is ultimately not serious, a dilettante’s distraction. (I suspect my real worry is that it makes criticism too fun, when it should be work.) With Davenport, the minutiae have weight. He can stake out a thought-world with a few pegs: “In 1840—when Cooper’s The Pathfinder was a bestseller, and photography had just been made practical—an essay [by Poe] called ‘The Philosophy of Furniture’ appeared in an American magazine.” (He assumes you know who Cooper and Poe are and what they signify; he doesn’t waste your time with potted biography.) Or he will make a larger digression when the subject has sufficient gravity; discussing a contemporary who interacts with Paradise Lost, Davenport inserts a four-page aside on Milton’s life, world, and art that is the finest introduction to the great poet I’ve encountered. Other times he only hints at connections the reader’s imagination must flesh out. When he notes, for example, that the fearsome Jesuits who taught Joyce were colleagues of Hopkins, a bookshelf in our brain creaks open to reveal a hidden passage.6

Elsewhere his love of detail simply models good reading, as in a trenchant critique of Richmond Lattimore’s Odyssey:

Professor Lattimore adheres to the literal at times as stubbornly as a mule eating briars. When, for instance, the Kyklops dines on Odysseus’s men, he washes his meal down with “milk unmixed with water.” But why would anyone, except a grocer, water milk? The word that makes the milk seem to be watered is the same as the one that turns up in the phrase “unmixed wine,” meaning neat. But even there the wine is unmixed because it is for dipping bread into; so the word comes to take on the latter meaning. What the homely Kyklops was doing was dipping the meat in his milk.

It’s a great example of how Davenport reads. He triangulates deep knowledge of the original text against its cultural context and his own experience of real people in our world, with common sense crafting the final image—another work of interpretive imagination.

The certainty in that last passage illustrates another characteristic feature of the Davenport style: his serene, unshakeable confidence. One can leaf through Geography at random and turn up dozens of similarly assured, sometimes inscrutable proclamations:

“What we call the twentieth century ended in 1915.”

“The poet, like a horse, is a mythological creature.”

“Art is man’s teacher, but art is art’s teacher.”

“We have paid too little attention to Whitman’s subjects.”

“We have a wrong, vague, and inadequate appreciation of Stephen Foster.”

“One can read The Cantos as a subtle meditation on whether stone is alive.”

These essays, for all Davenport’s admiration of Montaigne, are in no way attempts—they’re more like reports, intelligence in the military sense. The thinking and synthesizing they evince has happened somewhere off the page; we are being given the results. Who does he think he is? We are not used to this kind of assertive criticism; fashions have changed, and today’s critic is more likely to hedge and imply and frame ambiguities where Davenport rushes in without so much as a “perhaps.” It often seems like he’s making snap judgments, though that isn’t to say there’s anything provisional in them: They are the instinctive responses of a sensibility trained to reach its apotheosis through long attention and practice—reading Davenport can feel like watching a gifted athlete or a great jazz musician. And once he makes a judgment, he holds on to it. It is possible, over the whole of Geography, to catch him revising an opinion, but it is always a refinement, never a reversal.7 His are not sophist opinions for hire; whether he seems correct or ludicrous, even when we don’t fully understand what he’s talking about, there is a harmony in his convictions, and a charming inability to not take things seriously.

HIS IS THE KIND OF TONE that could nowadays get one called pretentious, a common accusation in a marketplace that has so devalued the virtuosic performance of knowledge and understanding, preferring to reduce the first to “information” and the latter to “capable of recalling the Wikipedia summary” (it is this same market that tempts us to view Davenport as a dealer of high-quality trivia). Well, is he? Pretentious writers, desiring to impress us, are necessarily shallow—they cannot sink too far into the material, first because they often don’t understand it all that well, but also because they must make sure you see how smart they are. (The better quality of pretentious writer is often very easy to follow, even as they affect complexity, because they know an audience is much more likely to praise what is understood.)

But while Davenport is not above snobbery, he does not preen. He is sure of himself, yes, and incredibly free with his knowledge—those are grounds enough for an uncharitable reader to accuse him of pretentiousness—but importantly, he is not a showoff. He can’t pose for us because he is simply moving too fast. The velocity of his thought, its firehose quality, is another core feature of his style. He moves fast because he can’t wait to get where he is going, and he tows us along in the wake of his passion, tossing out ideas a more tedious writer might wring for a whole book. His pure love for his material and his loose, discursive way with it evoke the character of two of his heroes, Ruskin and Thoreau, who might have recognized the vibrant power of his sincerity—that deep and knowing earnestness, uncompromised by naïveté.

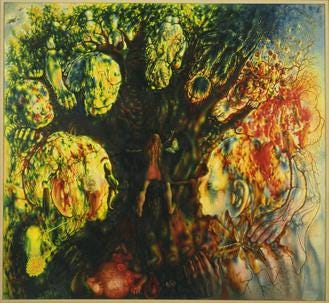

Of course, the same sincerity leaves him vulnerable to certain charges. His tendency to find meaning everywhere can lead him into the narrow, tautological precincts of conspiracy theory, as when he offhandedly declares John the Baptist’s severed head to be a type of Orpheus’ without pausing for even a moment to consider what might make them different. (I can practically hear his eyes roll at the vulgar suggestion it might be historicity.) He is a bit of an easy mark, particularly when it comes time to anoint living heirs of the literary and artistic trends he is interested in. I confess I cannot see much in the work of Jonathan Williams or Pavel Tchelitchew; their glossy layers of myth on myth, so attractive to Davenport, strike me as so much navel-gazing, his reading of them a glorified Easter egg hunt.

But then, Davenport is an enthusiast; on the whole, he prefers to spend time and ink on praise over condemnation—which is fortunate for him, because he is at his ugliest when negative. In a deprecatory mood he turns supercilious, a disdainful mandarin in a snit who cannot believe people could actually like the garbage they do.8 At other times he is full of Miniver Cheevy-ish self-pity at his misfortune to be born into the twentieth century.

And then there are greater faults: his apologisms for the antisemitism of Ezra Pound show an extraordinary failure of judgment, one related to his snobbery and his sincerity. (If there is a unifying figure among the forty essays in Geography, it is Pound, whom Davenport considers “the very archetype of the man who cared about things”—a description that betrays the depth of his vision-clouding affinity.) Davenport cannot allow that the maker of such beautiful, rich objects could fall into anything so base as plain old stupid bigotry. The genius must be insane, his sensitive soul driven to madness, Davenport suggests, by contemplating the injustices of finance capitalism. (Pound, the social justice warrior!) Outside a few halfhearted fulminations against “usury”—further homages to Pound, in their way—Davenport is essentially indifferent to political thought, or morality in general.9 His great attraction to utopian projects like those of Fourier and the Shakers, and his hatred of the sort of technological progress represented by the automobile—these play out entirely on aesthetic grounds. Critics can, of course, pursue whatever angles they like, but Davenport’s preoccupations make clear the reason for his sudden interest in Pound the political economist: He is grasping for something that might absolve his master.10 Ignore that stuff, he seems to say, focus on the poems—an ugly and incongruent failure of imagination.

It is disheartening to see Davenport deliberately curtail the scope of his reading in this way: As he demonstrates with his gloss on American Gothic, one of his great themes is that works of art are deeply embedded in overlapping contexts—personal, historical, mythical—and to foreclose any one of them is to fail to see. “Art,” he says in an important paragraph, “is the attention we pay to the wholeness of the world. . . . [I]f we knew enough we could see and give a name to its harmony.” In his confidence, Davenport asserts the world has a wholeness, a meaning. His refusal to see Pound in larger perspective is a turning away from this vista.

THE CENTRAL TASK OF GEOGRAPHY is to catalogue the methods by which meaning inheres in symbols. We have almost ceased to believe it can at all; if there is any unity among the art and literature most talked about now, it is a belief we must state what we think and feel explicitly—to our poverty, Davenport argues. By way of example, he presents us with a wooden pole inscribed with a series of rhomboids by a Dogon craftsman in Mali. The casual Western observer might think the shapes have been linked into a pattern that doesn’t mean anything in particular. It is actually a figuration of the ark that carried human and animal life descending from the heavens to the earth:

We have a vocabulary of responses to these signs, possibly all wrong, and probably projections of our way of seeing the world. We live in a decorated world, a frivolously decorated world, and thus see the Dogon graph of the primal ark’s descent as a primitive pattern, something daubed by simple black souls.

The symbolic is a default mode of representation for most humans, says Davenport; the things we make mean things; only a truly vapid culture would ignore this, would even have a category for the merely decorative. In this way he is deeply humanistic. He insists that people make extraordinary objects, and to claim someone is ‘reading too much into’ them is a degradation.

This brings us to Geography’s original cover, Davenport’s drawing of a frieze with two dancing girls. By the end of the book, we see what he is trying to tell us: This fragment is not mere decoration—pretty girls carved by a bored mason thinking about pretty girls—but part of a totality of social and ceremonial meaning. Shine a bright-enough critical light on it, he suggests, and like a prism, it will refract the whole rich spectrum of the world that created it.

“Art is the attention we pay to the wholeness of the world”: This is an assertion not only that the world has a wholeness, but that it is an intelligible wholeness—we can see and talk about its wholeness. Over and over, he emphasizes the importance of seeing, really seeing, and attending to what our sight tells us. Attention is everything for Davenport, the solvent of all complexities. “Familiarity is the condition whereby all [his] work renders its goodness up,” he says of the ferociously difficult poetry of Louis Zukofsky—but this is Davenport’s stance toward everything.

His tools are simple: enumerating, comparing, juxtaposing, pattern-finding. Although Geography takes up some of the most complex literature in English, Davenport remains faithful to those basic techniques of analysis. They may need to be taught, sure, but they don’t require credentials to use: “The body of knowledge locked into and releasable from poetry can replace practically any university in the Republic.” He loves the feral intelligence of oddballs who stood askew to the intellectual trends of their day: Ruskin, Hopkins, Thoreau, Fourier, Buckminster Fuller. For all his snobbery, there is a great egalitarian streak in Davenport. “I am not writing for scholars or fellow critics,” he says in a different book, “but for people who like to read, to look at pictures, and to know things.” The symbols of a work of art belong to all of us, hermetic or arbitrary as they may seem at first. We can see them, says Davenport, if only we pay attention and have a little curiosity, and maybe read a few books, not scholarly ones: Homer, Ovid, the Bible.

Don’t let these last invocations fool you. Unlike growing numbers of soi disant defenders of “the Great Books,” who uphold them instrumentally, for the sake of “Western identity” or being a better person or possibly just to hawk their own book (rarely discussing any specific great book in detail), Davenport has the gall to just assume that his many subjects are valuable for their own sake and that they matter to us, and he goes on to discuss their particulars with loving attention. When he called Pound “the very archetype of the man who cared about things,” his fingers closed around the root of his own genius. Those mountebanks see reading the classics as a project of acquisition: they assume their canon, however defined, is a reservoir of knowledge that can be extracted and exchanged in turn for wisdom or some other benefit. But Davenport’s inquiries are thrillingly open-ended. He unfolds the work just enough to demonstrate it could continue unfolding—that, like Borges’s map, it could cover the whole world, should the reader have sufficient time and imagination.

Among the many catalogues Davenport includes in this volume is his outline of “that scarce genre which we can only call a book, like Boswell’s Johnson, Burton’s Anatomy, Walton’s Compleat Angler.” It’s a great description of a shelf that ought to contain Geography, too. Like each of those shaggy masterpieces, Davenport’s book invigorates us, zaps us with new realizations of what inquiry and imagination can yield. It offers a reminder of what a satisfying intellectual life might be—and what cold leftovers we often settle for instead.

Now mercifully returned to print by Godine Nonpareil, albeit in a chunky squarish paperback difficult to get your hands around or keep open, and bearing a large photo of its famously self-effacing author, which he might be mortified to discover had replaced his own illustration for the original jacket, “a quotation in my steel-engraving style of a metope at Paestum, two Maenads, possibly Bacchantes, doing a fling, or round dance.”

I count eight: Davenport’s imagination occasionally goes beyond mere discovery.

Wood always referred to them as father and daughter, and Davenport certainly knew it. The artist’s intention is not nothing to him, but if it is swimming against the current of the ages, it is perhaps best left alone.

It is tempting to continue quoting choice bits until the entire passage is reassembled here. I’ll limit myself to one more: “The curtains are bordered in a variant of the egg-and-dart design that comes from Nabateaea, the Biblical Edom, in Syria, a design which the architect Hiram incorporated into the entablatures of Solomon’s temple . . . and which formed the border of the high priest’s dress.” Readers who do not enjoy this kind of juxtaposition, or who think it farfetched, may find something useful in Davenport but are likely to be immune to his charms.

See also: Hugh Kenner, Eliot Weinberger, Alexander Theroux, the novels of W.G. Sebald and David Markson.

Davenport will occasionally detour well out of his way to show off a nugget totally unrelated to anything, but he generally confines these excursions to footnotes and always makes it worth the trip. Consider his description of a photo of Poe “inspecting the fossil skeleton of a prehistoric horse: a photograph still unknown to the Poe scholars.” (Aspiring stylists would do well to meditate on the work accomplished by that second “the.”)

Our opinions change, but as trees do, not clouds, says Ruskin.

This tendency is most embarrassing when Davenport finds himself actually sharing an opinion with the great unwashed: A passage reflecting on the popularity of Tchelitchew’s Hide-and-Seek is little more than a real-life version of a classic Onion editorial, “I Appreciate The Muppets On A Much Deeper Level Than You.” (Of course, when it suits him—to tweak his fellow academics, for instance—he will affect the part of Mother Davenport’s fried-baloney-eating son, who don’t hold with fancy Yankee notions. It’s the flip side of his interest in cranks and outsiders: my guess is the Duke-Oxford-Harvard man wished he were one of them.)

The writer Phil Christman addresses some of the larger issues this amoral position entailed in Davenport’s life in his review of a collection of correspondence between Davenport and Hugh Kenner for The University Bookman.

None of Geography’s flaws, great or small, require twenty-first-century eyes to see; all of them were pointed out by reviewers of the first edition, and not in little journals only but the New Yorker, Harper’s, and the New York Times.