GOP Senators Should Pursue a Budget Deal with Biden

Learn the lessons of the infrastructure bill and participate in the essential business of governing.

Should the Republican senators who struck the infrastructure deal stay at the negotiating table for the coming budget bill? As far-fetched as that seems, they should be ready to keep talking if the opportunity comes around, which it might. They also could make the possibility more likely by announcing their openness to another compromise.

At the moment, the prospect of a second bipartisan bill is remote, as the Biden administration and Democratic leaders in Congress want a partisan measure to secure long-sought goals. The calculus might shift, however, when what is being asked of the party’s moderates fully settles in. It will not be easy to hold all Democrats together to support a multi-trillion-dollar tax increase.

Moreover, the “pay fors” now being kicked around are underwhelming, substantively and politically. There is a push for a major corporate tax rate increase, an increase in the top individual rate, and higher taxes on capital gains. All of those might be possible, but they will not come close to covering the $3.5 trillion in planned spending, especially when the affected parties start voicing their objections. Other items on the still-developing list are longshots, or minor. Taxing the individual retirement accounts of rich people? It is hard to see this getting through a basic fairness screen. Prescription drug reform can produce major savings, but it will be difficult to get the most ambitious versions through Congress, such as direct price-setting by the federal government.

Even with these caveats, however, enactment of a partisan bill remains possible, and perhaps probable. Among Democrats, the view is that it’s now or never for this agenda, which is powerful motivation for moving forward. The party may line up behind whatever can be covered by the tax hikes that can pass; new programs could be trimmed as needed by sunsetting them earlier than planned (with the expectation of passing extensions later).

For their part, most in the GOP are relieved to be on the sidelines, as the planned bill is focused on matters—taxing the rich, climate change, social spending—that they would prefer to avoid.

And yet, there also is much for Republicans to lose from standing aside. The Democratic objective is nothing less than a major revision of the nation’s social contract. Unless the GOP is prepared to cede governing the country entirely to the other party (while focusing, as it does now, strictly on cultural conflict), it cannot afford to be a nonparticipant. It must either engage directly in the major questions on the table, or offer serious plans for addressing them on the party’s terms when the opportunity arises.

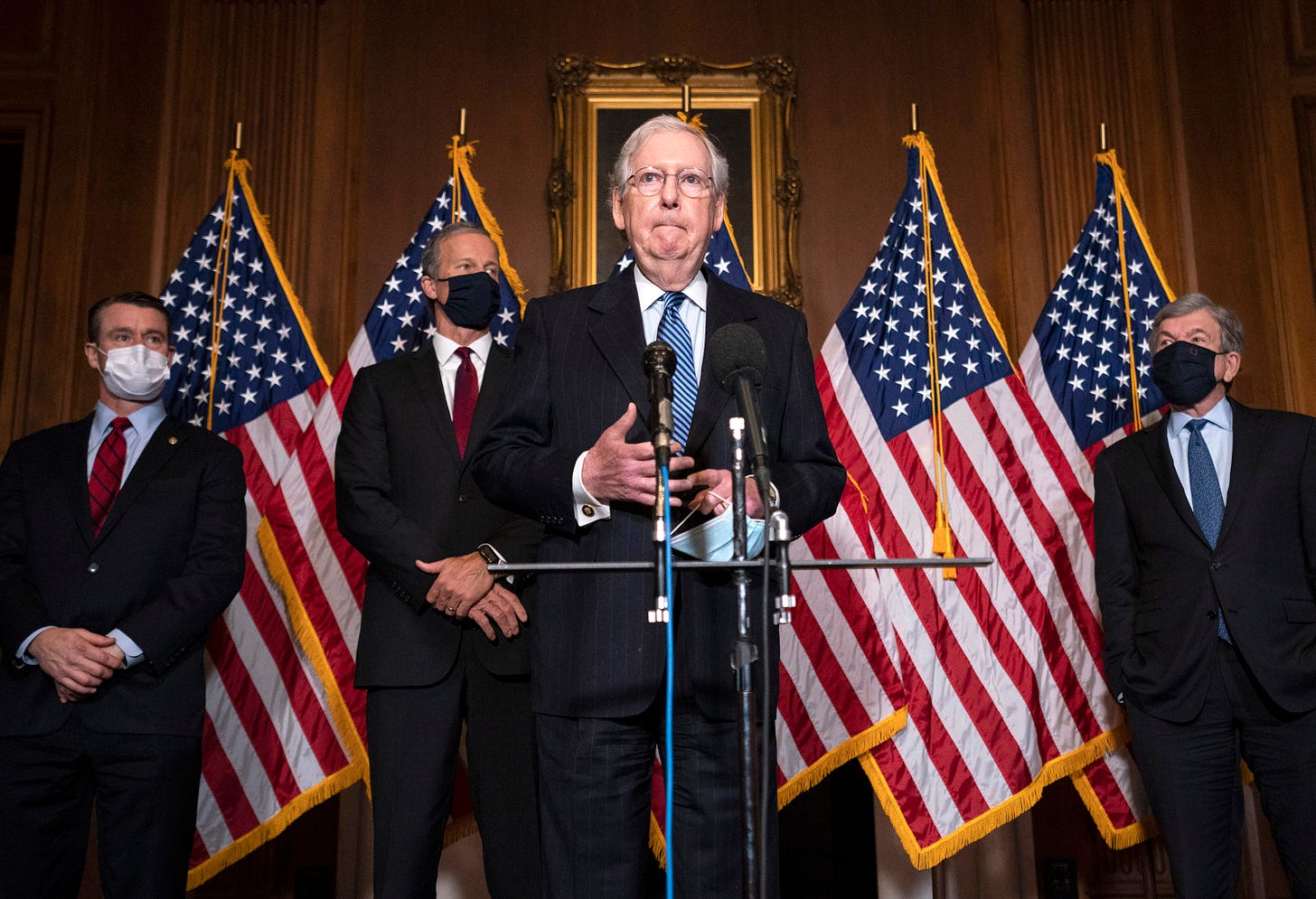

The infrastructure deal demonstrates the benefits of engagement. The Republicans who negotiated the bill, while not universally praised, are seen as taking part in the essential business of governing, and the give-and-take which is natural in the nation’s legislative body. The resulting bill is adequate for its intended purpose, and thus will be seen in time as worth the effort. Its provisions also will endure, as bipartisan bills are very difficult to reverse once they are enacted.

That does not mean the deal is flawless. The sponsors tout its cost-neutrality, but they rely on gimmicks to make that argument. The actual budgetary effect will be to add hundreds of billions of dollars to future deficits, which is certainly not what the country needs. Further, the more than $0.5 trillion in new spending is sure to include significant waste, and much counterproductive meddling in the private economy. It is perhaps a sign of political normalcy that many Republicans are aware of these defects and yet accepted them as the price to be paid for influencing the bill’s major provisions. The bill would have been worse on these counts without their participation.

The infrastructure deal’s value to the GOP was on display in the apoplectic response from the nation’s most recent one-term president. He denounced it as “socialist,” even though he surely would have hailed it if it had passed during his tenure. It does not seem to have occurred to him or his enablers that their incompetence at governing, amply demonstrated by their inability to secure a similar bill when it was possible to do so—how often was “infrastructure week” announced with no follow-through?—contributed mightily to his exit after one term. Strong Republican support for the bill’s enactment would create some beneficial distance between current officeholders and the former president.

The coming budget bill will be a harder test for both parties. So long as Democrats are intent on enacting a tax increase unlike any seen in the nation’s history, there will be no GOP participation. But it is not a forgone conclusion that the Democrats can carry through on this plan.

What might be possible is for the centrist members of both parties to recognize that aspects of the nation’s economic life are badly in need of revision, and the best outcome would be a stable, bipartisan plan that includes some objectives both sides consider important.

To be taken seriously, the Republicans willing to engage in such a negotiation would need to give up on the idea that a net tax increase is always and everywhere to be opposed. That conviction, long a shibboleth for a certain kind of Republican, is untenable given the nation’s deteriorating fiscal outlook. If every bill that comes along raising taxes (on a net basis) is per se unacceptable, the GOP will have removed itself from addressing one of the most serious challenges—unsustainable debt—confronting the nation. If the party also refuses to take any action on climate change, it is on the verge of becoming entirely irrelevant.

The senators who negotiated the infrastructure bill could show they are serious by announcing their willingness to accept a limited amount of new revenue if they have a say in how it is raised. The best policy would be to create a new carbon tax that would increase costs for fossil-fuel dependent industries, and thus incentivize a broad, market-driven shift toward lower carbon emissions. The revenue could be used to strengthen the nation’s safety net, perhaps through bipartisan revisions to existing tax credits, or possibly through improvements in other income-support programs. It may be possible to reduce future deficits too.

There are opportunities for compromise on other issues as well. The Senate came close to passing a bipartisan drug-pricing bill during the Trump years. It was not everything Democrats now want, but it was within reach, and could be again (with some sensible revisions). The Medicare Hospital Insurance trust fund also is nearing depletion; pushing off insolvency will require taking some unpopular steps, which is best done in a bipartisan plan.

Bipartisan budget bills used to be the norm, as President Biden well knows. In 1990, and again in 1997, the parties struck deals covering major aspects of the tax code and social spending; significant policies from those measures remains in effect today. A deal struck in 2021 could have similarly lasting consequences.

Perhaps the most important reason for Republicans to go down this road is what it would mean for the party itself. Striking a major deal with Democrats would represent a clear break with the party’s recent behavior, and a step away from treating the challenges of governing the country as less important than the culture war. There are probably only a handful of Republicans in the House and Senate who might be willing to engage in such an exercise. The party’s viability may depend on whether they have the opportunity to do so.