High Crimes and Misdirection

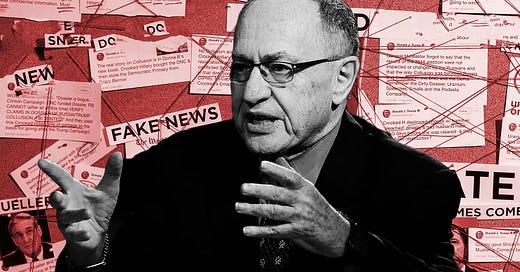

Alan Dershowitz argued before the Senate like a defense lawyer, hiding the inconvenient facts.

When Alan Dershowitz told senators that the Constitution’s standard for impeachment is a bright-line rule that covers only crimes, not abuses of power, you could practically hear the sigh of relief from roughly half the room.

I don’t blame Republican senators for welcoming Dershowitz’s argument with open arms. I don’t envy the awesome responsibility that senators bear in impeachment trials: Making difficult factual judgments about what the president did and why he did it; or difficult legal judgments about whether the president’s actions rise to the level of the Constitution’s “Treason, Bribery, or other high Crimes and Misdemeanors”; or the difficult prudential judgments about whether the proper remedy is to remove the president from office.

Placed in the situation of having to make such decisions, any member of the president’s political party would naturally start looking for an escape hatch. Alan Dershowitz opened one for them, by arguing sweepingly that a president does not commit “high crimes and misdemeanors” unless he violates criminal statutes. (You can find the video here, a rough transcript here.) By this argument, no abuse of power, however grandiose, could be impeachable unless it violated a separate criminal law.

But before Republican senators rush to Dershowitz’s emergency exit, they should understand what Dershowitz didn’t tell them. Dershowitz is a great defense lawyer and he presented them with scattered quotes from Alexander Hamilton and James Madison, which he presented as evidence in support of his constitutional argument. But with each of those figures, he left out evidence that undercuts his case.

First, let’s consider Dershowitz’s mischaracterization of Alexander Hamilton. Dershowitz was right when he repeated Hamilton’s worry that impeachment trials would descend in knee-jerk partisanship. (Hopefully Republicans and Democrats alike took notice.) He was right to quote Hamilton’s explanation, in Federalist No. 65, that impeachment involves “those offenses which proceed from the misconduct of public men, or, in other words, from the abuse or violation of some public trust.” But Dershowitz goes one step further when he asserts that Hamilton was writing only about “specified crimes,” and not “expanding the specified criteria to include . . . misconduct, abuse, or violation [of some public trust].”

This reading of Hamilton is plausible only so long as you don’t actually read Federalist No. 65. Because anyone who does read Hamilton’s essay—and not just the quote that Dershowitz provided—will see that Hamilton expressly rejects Dershowitz’s argument that impeachment covers only crimes.

Impeachment, Hamilton wrote,

can never be tied down by such strict rules, either in the delineation of the offense by the prosecutors, or in the construction of it by the judges, as in common cases serve to limit the discretion of courts in favor of personal security. [emphasis added]

This is one of the reasons why Hamilton argued that the Senate was a better trier of impeachments than the Supreme Court: impeachment involved not just the normal application of laws and facts, but rather an “awful discretion” not bound down by normal legal standards, one for which the senators would ultimately have to bear political responsibility.

Second, let’s consider Dershowitz’s mischaracterization of James Madison. As with Hamilton, Dershowitz begins with the truth: at the Constitutional Convention, Madison opposed listing “maladministration” among the grounds for impeachment, because such a low bar for impeachment would risk turning the president into a mere prime minister: “So vague a term will be equivalent to a tenure during pleasure of the Senate.” Instead of “maladministration,” the Framers added “other high Crimes and Misdemeanors.”

Again, this reading of Madison is plausible—but only so long as you’re not actually familiar with the other things that Madison said about impeachment. And again, Madison’s other arguments directly contradict Dershowitz’s presentation. In Virginia’s ratifying debates, Madison specifically argued that if senators feared that the president might abuse the pardon power, then the Senate could preemptively remove him from office in an impeachment trial: “if the President be connected, in any suspicious manner, with any person, and there be grounds to believe he will shelter him [with pardons], the House of Representatives can impeach him; they can remove him if found guilty.”

This single argument by Madison, which my colleague Ramesh Ponnuru has flagged repeatedly, contradicts Dershowitz’s assertion that Madison believed that presidents could not be legitimately impeached and removed for actions that aren’t criminal acts. Abusing the pardon power is not a crime yet Madison specifically singles this non-criminal abuse of power out as behavior worthy of impeachment and removal.

In fact, Madison’s argument goes a good bit further: His words reflect a belief that the House and Senate could impeach and remove the president preemptively, even before the president had actually committed—the act in question.

In mischaracterizing Madison’s views, Dershowitz hopes that his audience will fall for a false choice: Namely, that because Madison rejected the extremely low and malleable standard of “maladministration,” then Madison must have adopted the extremely high and concrete standard of “criminal acts.” Dershowitz assumes away—or rather, tries to obscure—a third option: Namely, that “high Crimes and Misdemeanors” was intended to include an undefined category of crimes and other miscarriages of public responsibility.

This third option is the most reasonable interpretation of what constitutes “high Crimes and Misdemeanors.” It is not an invitation for senators to turn impeachment into whatever they want it to be, but a charge to senators to make hard legal and prudential judgments about what abuses of power and violations of the public trust are so grave that, even if not technically illegal, still merit constitutional impeachment and removal.

In the Senate, Dershowitz presented himself as an ardent defender of the Constitution’s original meaning. This is interesting, since not so long ago Dershowitz was mocking originalist judges as the intellectual descendants of antebellum slaveholders and 1950s segregationists. Quoting the infamous Dred Scott case in a 2004 book, he wrote:

Contemporary judicial nominees who glibly recite the expected formula of original intent or understanding should read [the Dred Scott opinion] and be asked whether they would have joined the majority decision in Dred Scott—and if not, why not? I have yet to hear a persuasive explanation of how honest ‘originalists’ could have wriggled their way out of the majority conclusion in Dred Scott or how they could have agreed with the Supreme Court’s unanimous decision [in Brown v. Board of Education].

Reading that attack on constitutional originalism, I’m struck by the irony. First, the same professor who once mocked “glib” originalist judges is now, in the biggest case of his life, making truly glib arguments about the Founders’ views.

Second, he’s trying to win over a roomful of Republican Senators whose major achievement in the last three years has been the appointment of dozens of originalist judges—the very kind of judges who Dershowitz mocked.

The Senators take the Founders’ views very seriously in confirming judicial nominations. That is as it should be.

Let’s hope that, in deciding this impeachment trial, they take the Founders’ views seriously, too. Or at least more seriously than Dershowitz would have them do.