THE CLASH IN THE HOUSE REPUBLICAN CONFERENCE this Congress began with the prolonged speakership balloting in January, flared with the ousting of Kevin McCarthy last week, and even now is still stumbling along with uncertainty. But the basic reason for all this instability—the GOP’s prosciutto-thin majority in the House—also creates an unusual opportunity. Could pragmatists finally claim the leverage they need to defeat the extremists who have taken over the GOP?

It will only take one member to get the ball rolling. Could it be Rep. Ken Buck, who says he is refusing to vote for either Steve Scalise or Jim Jordan in the speakership contest because of the Big Lie? Or the unpredictable Rep. Nancy Mace, who joined the Gaetz rebellion last week and this week rejected Scalise as too racist? Or the Ukrainian-born Rep. Victoria Spartz, also uncommitted in the speakership contest, who is distraught that she “cannot save this Republic alone” and has decided not to run for re-election? Or Rep. Don Bacon, who said the extremists are “destroying our conference and apparently want to be in the minority”?

Over the course of this year, it seemed at times as though the bipartisan Problem Solvers Caucus—of which Bacon is the whip—could play a pivotal role in resolving major disputes in the House, with such optimistic headlines as “Problem solvers can, at long last, be kingmakers.”

It made a lot of sense, mathematically anyway.

With the House GOP’s five-seat majority acting at times like a three-ring circus, circumstances seemed ideal for the cross-partisan group to wield power. Founded in 2017, the Problem Solvers Caucus has 64 members, with 32 from each party—which means that just the GOP half of the caucus is six times the size of the party’s margin of five seats in the House.

Even before McCarthy was sworn in as speaker in January, it seemed clear what would unfold: His leadership would be consistently pressured from the right, and would need Democratic votes at the ready to hold leverage over the extremists in his caucus. That would be the role of Problem Solvers, to secure additions from the Democratic side of the aisle greater than the subtraction from the right fringe.

But those expectations have come crumbling down, with Republican members of the Problem Solvers Caucus threatening to quit en masse. They are outraged that their Democratic counterparts did not cross party lines to save Kevin McCarthy’s speakership last week.

The choice that Democratic Problem Solvers faced was to either do what every single member of Congress does every single speaker vote—going back at least seven decades, only one representative has voted for a speaker candidate of the other party1—or to cross party lines and vote with Lauren Boebert and Marjorie Taylor Greene. The Democrats understandably took the normal course of action.

Calculation, Not Courage

“COURAGE” IS ALWAYS THE BUZZWORD for centrist politicians. But political calculations also must be run to stabilize the House. It is not a coincidence that two-thirds of the House Republicans from districts won by Joe Biden are members of the Problem Solvers Caucus. Courage does not magically burst within the souls of dozens of members of Congress, it is often born of political necessity.

But so far in this Congress, the Problem Solvers have been short on both courage and calculation. They tout their bipartisan cred on the campaign trial and get cash from No Labels supporters—a win-win. As the election analysts at Split-Ticket have shown, Republican Problem Solvers run more than 3 points ahead of their party, better than any other caucus in Congress. It is a good brand.

But now something more is needed of them than the buzzword and the brand. As the speakership fight moves into the next, and likely final, phase, could the Problem Solvers play a decisive and constructive role?

With Enough Leverage You Can Move the World

MATT GAETZ NEEDED JUST FOUR colleagues to go from a back-bencher under an ethics investigation to deposing a speaker for the first time in history. He got eight votes, well more than needed.

But that majority math works in both directions: Any individual moderate Republican can do the same thing Gaetz did, taking control of the speakership selection process with just a tiny band of allies. There are precedents at the state level—what we might call laboratories of centrism in legislatures around the country. If lawmakers in Texas, Alaska, Ohio, and New York can figure it out, why not members of Congress?

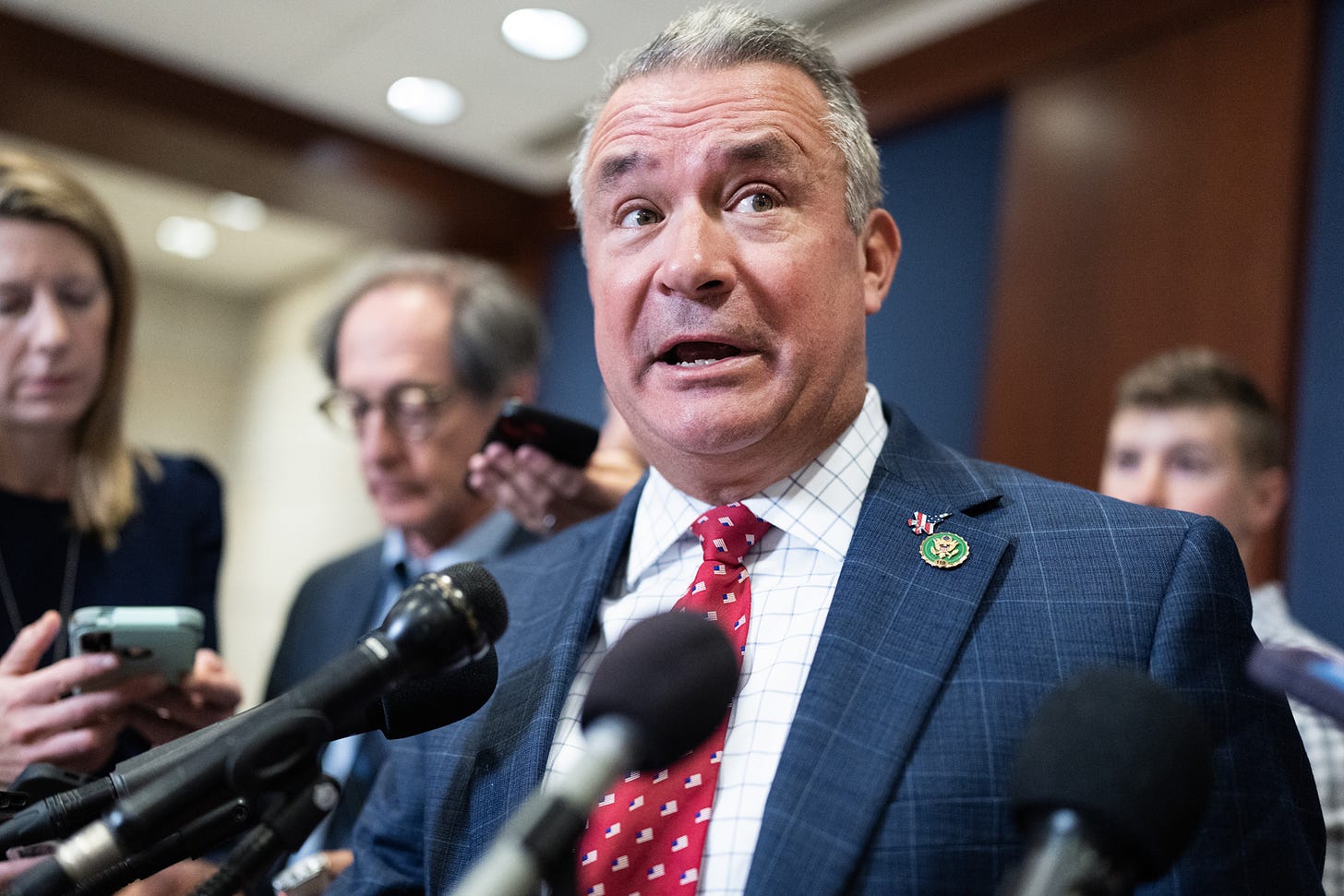

Let’s go back to Don Bacon, who whipped votes for the Problem Solvers Caucus. How does he win Nebraska’s 2nd Congressional District while Biden is beating Trump by 7 points among the same voters? He runs as a bipartisan problem solver. He gets endorsed by his Democratic predecessor. Last week, Bacon gave a local TV news interview that the station literally titled “Rep. Don Bacon encourages bipartisanship after McCarthy ouster.”

And now, as the House inches toward picking its new speaker, Bacon could exercise powerful leverage over those Republicans who, he charges, “don’t respect” the House. He would need only four additional votes to stall the process of picking a new speaker as Gaetz did—but for constructive purposes. Bacon would have a willing partner: Minority Leader Hakeem Jeffries could not be clearer in seeking a bipartisan governing coalition. By publicly opening negotiations with Jeffries, Bacon would have leverage over Scalise to strengthen the moderate wing of the GOP—or else his Party of Five can form a bipartisan governing coalition with Democrats.

And once that gets out, the whole game changes. National media coverage will shift away from the extreme and bizarre—like Marjorie Taylor Greene’s opposition to Scalise over his cancer diagnosis, and others for his KKK baggage—to the who, how, and when of a bipartisan governing coalition.

This renegotiation over House control is about leverage. Extremists know how to use it—and moderate Republicans can only get it by threatening to join with Democrats.

This course isn’t without risk. If the gambit fails, the GOP majority might be inclined to punish those Republicans who reach out to the Democrats, perhaps by stripping their committee assignments or by working for their defeat in future elections. But the potential reward—strengthening the institution of the House, making the rules and the leadership more stable, and perhaps contributing meaningfully to major policy issues—is too great to ignore.