How ‘Left Behind’ Got Left Behind

A changing political mood among evangelicals has many believers imagining the end of the world differently than they used to.

“I WISH WE’D ALL BEEN READY.” The Late Great Planet Earth. A Thief in the Night. The Left Behind series. If any of these rings a bell for you, you may be familiar with one of evangelical Protestantism’s unique contributions to the American imagination: an apocalypse heralded by the sudden disappearance of millions of people from all over the world. I’m talking, of course, about “the Rapture.”

Arguably, we reached peak Rapture-mania in American culture around the turn of the Millennium (“Y2K,” as many called it at the time), when the Left Behind books were still selling millions of copies but before Nicolas Cage had been tapped to play a leading role in one of the film adaptations. The Rapture’s cultural popularity was rooted in its spiritual importance for millions of American Christians. I can attest to this: I was raised in evangelical church communities where anticipating the Rapture and awaiting the ever-impending return of Jesus was a major component of our faith and devotional life. Scholars have even described the widespread psychological phenomenon of “rapture anxiety,” a theologically induced trauma affecting Christians afraid they might remain earthbound on that prophesied day. The overriding focus of books, movies, and music about the Rapture is what comes after for those who have been left behind: misery, hardship, and a brutally fraught path to redemption for those who choose to follow God after the abrupt disappearance of the Christians.

But then the Rapture, well, sort of disappeared. If you assume all evangelical Christians are motivated by the thought of a coming Rapture today, you may have missed the new end-of-days mood that has taken hold within American evangelicalism. For many Christians on the right, the end times are no longer a source of dread and anxiety so much as an expected and even welcome opportunity for God’s soldiers to conquer the earth.

In theological terms here, we are talking about eschatology, the body of Christian doctrine focused on the end of the world and what comes after. But while eschatology is a category of Christian dogma—many denominations and churches having an eschatological section in their statements of faith, and some theologians have special expertise in it—historically, major shifts within this theological subfield have often closely followed evolutions in the collective evangelical mood or frame of mind. Eschatology emerges out of biblical interpretation, of course, but it is also uniquely entwined with how contemporary Christians are interpreting the world around them. This is because it is where theologians sketch out the future they believe we’re bringing about, the cultural persecutions believers can expect to face, or the societal conquests Christians should feel entitled to undertake.

Many of the debates among Christians about eschatology hinge on an image from Revelation 20: a thousand-year reign of Christ. Is this reign literal or symbolic? Is it already happening now, or will it happen in the future? These questions are threaded through the different futures imagined in competing accounts of the end times.

In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, American Protestant eschatology was overwhelmingly optimistic, envisioning hopeful scenarios in which Christians could triumphantly build the kingdom of God on earth and gradually reform human societies to attain moral perfection, which would then bring about the return of Christ to earth. This was the eschatological disposition (sometimes labeled “postmillennialism”) that invigorated Christians’ participation in many early American reform movements, including the cause of abolition to end chattel slavery, “Sabbath reformers” hoping to prevent Sundays from being used for secular purposes (a principle that remains codified in many states’ blue laws), and the temperance movement to end alcohol abuse. The world needed fixing in Jesus’ name, and Christians thought they had the right tools for the job.

The Civil War poured cold water on this mood of Christian optimism. Christians fought on both sides during the war, all believing that they were battling for God’s preferred future. Historian Mark Noll has accurately characterized the Civil War as a sort of “theological crisis” in American Protestantism. After the war, the old postmillennial Christian optimism seemed less and less apropos.

It was in the aftermath of the Civil War’s devastation and ensuing disillusionment that a new eschatological mood took root, cultivated by a new generation of theologians who would come to be known as the Dispensationalists. This cohort turned the End-Times optimism of antebellum America inside out. They advocated a “premillennialist” understanding of the end times, which involved a deep pessimism about human culture. No longer would Christians seek to rehabilitate the world into a Christ-centered utopia: In the Dispensationalist vision of the future, the world will get worse and worse until Jesus raptures away the faithful Christians to heaven, an event that will trigger the rest of humanity’s rapid descent into chaos and judgment. After a great tribulation, the dispensational premillennialists argued, Jesus would come back, shake the world like an Etch-a-Sketch, and start his thousand-year reign on the blank slate of a new, perfected human civilization.

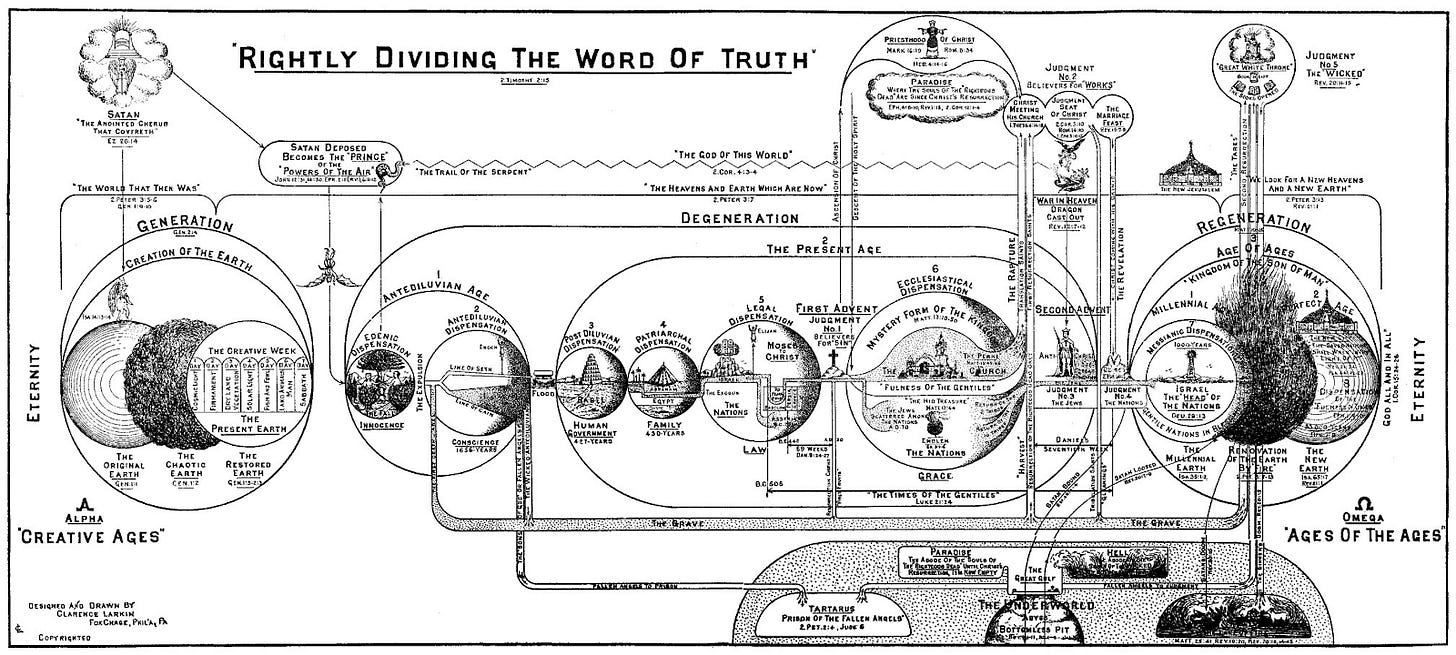

Dispensational premillennialist theologians read the Bible, especially its mysteriously futuristic passages, through the lens of a hard literalism and with an engineer’s need to diagram it all out. They created elaborate charts that described God’s actions in past and future “dispensations,” which are unique eras in the history of God’s redemption of humanity.

When the modern evangelical movement emerged in the 1940s, its leaders were, almost to a person, deeply influenced by Dispensationalism and its gloomy premillennialist eschatology. From that first generation of leaders to the one that led the movement at the turn of our own millennium in the year 2000, this melancholy posture of “holding on till Jesus takes us away” predominated among popular evangelical expectations for the future.

This theological outlook has been a major influence on evangelical politics and art since the inception of the movement. Rapture theology has consolidated generations of evangelical support for the state of Israel, because the reconstitution of Israel and the gathering of Jews in the eastern Mediterranean are crucial ingredients in the premillennial formulas to bring about Jesus’ return. It is also the well from which the famous—if not particularly high-brow—twentieth-century evangelical art I mentioned earlier was drawn: speculative, bestselling premillennialist books like The Late Great Planet Earth (35 million copies sold) and the Left Behind series (80 million copies sold), thrilling movies like 1972’s A Thief in the Night, and the several Left Behind cinematic adaptations.

IF YOU WANTED TO UNDERSTAND American evangelicalism in the late twentieth century, premillennialism and the Rapture are pretty good places to start. These are core features of the theological environment in which I was raised. When I was preschool-aged in the early 1980s, my family moved to join a premillennial Christian commune in Washington state to live off the grid and wait out the Rapture with a few other families on a farm. Because it’s premised on the world getting worse and worse, radicalized premillennialism encourages believers to retreat from society into enclaves.

But the dispensational premillennialist framework, once foundational to the political and theological imaginations of so many evangelicals, might be losing its pride of place in popular evangelical eschatology. I’ve spent the past three and a half years researching the theological ideas and Christian leaders who were central to instigating the January 6th Capitol riot, and what I’ve found has shaken all of my assumptions about American evangelicalism—a world I thought I knew intimately.

Since the advent of the Trump era, the evangelical landscape has undergone rapid shifts, often in turbulent and dangerous directions. To be sure, there are still plenty of evangelical premillennialists out there faithfully waiting on the Rapture. But their sequestering, defensive posture is becoming outmoded. Remarkably, the most prominent and powerful new leaders—the ones dedicated to fully recentering evangelical politics on Donald Trump, and who have grown their power and influence through their association with him—are overwhelmingly anti-Rapture. They believe Christians have a more active and forceful role to play in the end of the world.

The front-line captains of the American religious right today are overwhelmingly nondenominational, which means they are not accountable to larger organizations of churches or held to historic creeds or confessions of faith, and they are also charismatic, meaning they embrace miracles and prophecy and see the supernatural ethos of early Christianity as a model for current-day believers. They have also embraced a far grander vision for transforming American culture than any Rapture-waiter could imagine.

This up-and-coming eschatology is not as cohesive or systematic as dispensational premillennialism. It’s not as patiently optimistic or as content with gradual social reform as the postmillennialism of old. Instead, the predominant new charismatic eschatology hopes for a dramatic, militant Christian end-times revival to sweep the globe dramatically battling back the kingdom of darkness. If we could capture this theological vision of the future in a phrase, it would be “victorious eschatology.”

Proponents of victorious eschatology denounce the Dispensationalists as “defeatist” and “escapist,” too willing to sit on their hands and wait for Jesus to fix the world. These new leaders instead anticipate that the church will have to fight like (and against) hell to bring God’s kingdom to the earth, because Satan and his demonic minions will never cede the world without a fight. Victorious eschatology is optimistic about the future, but that optimism is premised on its adherents’ willingness to bring spiritual war to all non-Christian culture.

One of the central vehicles for victorious eschatology is the Seven Mountain Mandate, a popular framework charismatics use to envision this rapid transfiguration of society. Seven Mountain advocates believe that society can be divided into seven arenas of influence: the family, religion, government, education, arts and entertainment, media, and commerce. The future they are trying to bring about is one where Christians “conquer” all seven mountains in the name of Jesus, which will then allow conservative Christian morality and influence to flow down from the heights of power and influence. Trickle-down theocracy, you might say.

This Seven Mountain Mandate/victorious eschatology paradigm is central to the ideology of many Christian leaders who’ve endorsed Donald Trump, and it motivated some Christians to participate in the chaotic violence of January 6th. Many of the most influential leaders who propagate the Seven Mountain Mandate were present at the Capitol that day. They believed that Trump helped Christians capture some of the societal mountains during his term in office, and they were not about to give up that hard-won cultural territory by letting him be ushered out of office.

If radicalized dispensational premillennialism inclines believers to retreat into distrustful enclaves and leave the world to its fate, radicalized victorious eschatology pushes believers to triumphally (and, perhaps, coercively) impose their Christianity on whole societies. If we have eyes to see and ears to hear, we can observe this change in eschatological mood happening all around us as politicized Christians abandon their quietism and become more politically aggressive—even militant.

We can see it in the fawning devotion that many evangelicals offer Donald Trump, their divinely anointed heathen warrior king, sent by God, like the ancient Persian ruler Cyrus, to free God’s people from perceived captivity. We can hear it in the increasingly apocalyptic phrasing evangelical lawmakers are using to describe otherwise mundane policymaking. We can recognize it in the use of Seven Mountains rhetoric and symbols by Christian lawmakers and judges at the highest levels of our government. It’s evident in the fervent, hyperpoliticized evangelical worship rallies being held at our state capitals.

We are living in seismic and unpredictable times wherein American evangelicals’ hunger for a more worldly sort of power has been reawakened. If we don’t reevaluate our assumptions about evangelical politics after January 6th and amid the ongoing political radicalization of American Christians, we risk missing the signs that many conservative American Christians are developing more far-reaching—and extreme—political ambitions.