How One Business Management Theory Explains Donald Trump

Stanford Business School's Jeffrey Pfeffer predicted Trump, before Trump.

One of the persistent criticisms of President Trump is that he has continually violated well-established norms of political life. That would be bad. However a considerable amount of research in organizational behavior suggests another possibility:

That Trump’s actions, however objectionable, are not as unusual as we’d like to believe. To the contrary, his traits and behaviors are surprisingly representative of those who rise to power and maintain their authority.

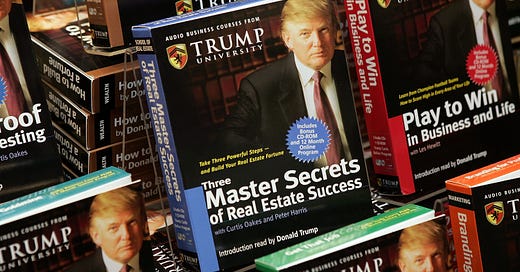

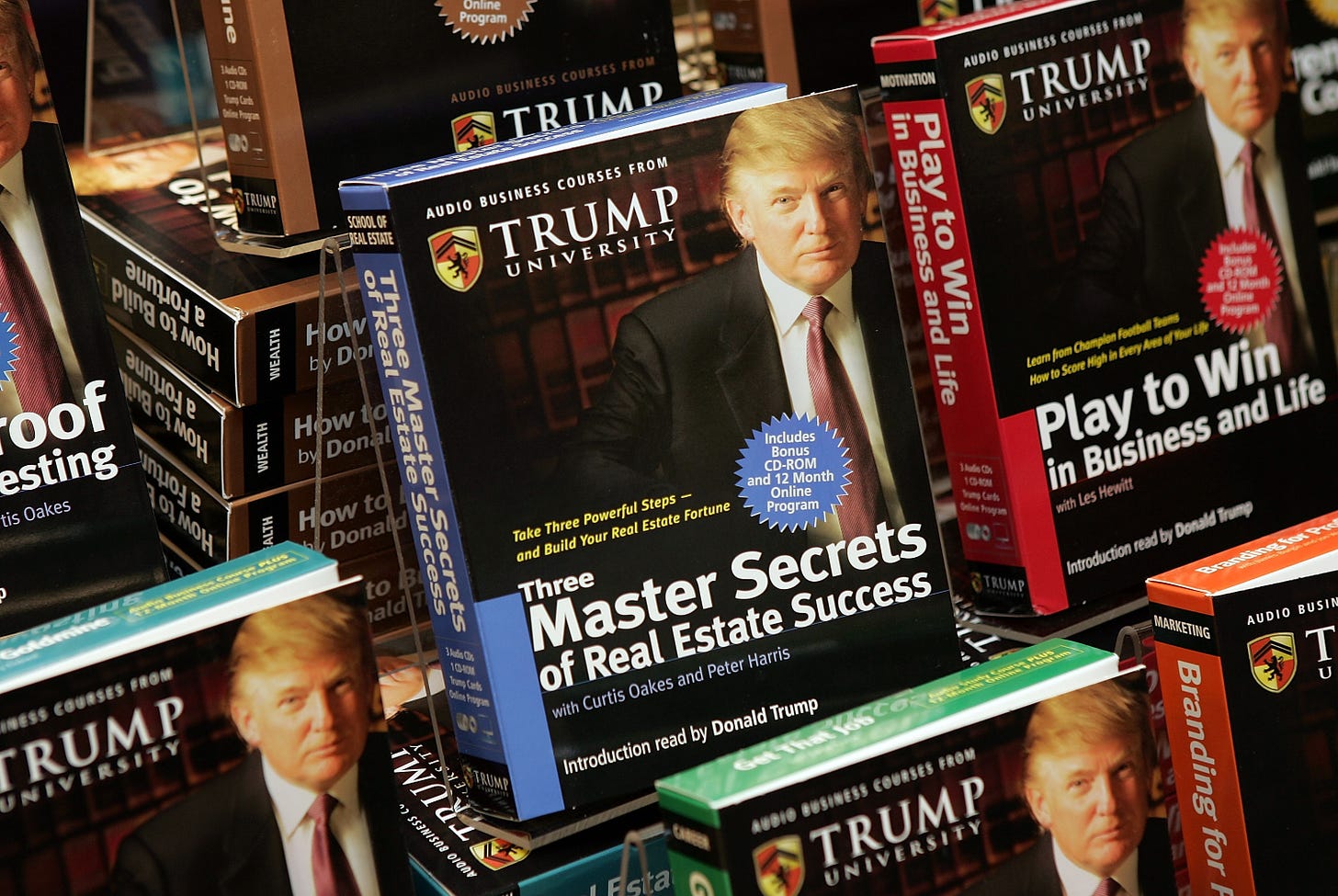

The pervasive disconnect between leadership as it’s preached and leadership as it’s attained and practiced has been captured with brutal concision by Stanford business school professor Jeffrey Pfeffer, who has studied and taught organizational behavior for over 40 years, and is perhaps best known for a course he teaches, “Paths to Power,” which offers students an unadorned perspective on this journey. He’s summarized his learnings in a pair of books, Power and Leadership BS, which together offer an unconventional counterpoint to the tendentious self-help literature so pervasive in the study of management. Both books were published prior to Trump’s election yet anticipate almost exactly the behavior patterns we’ve subsequently observed from the President.

Pfeffer’s underlying thesis is that most of what we’ve been conditioned to believe about power and leadership is wishful thinking, a fairy tale, a gauzy description of the world as we’d like to envision it, rather than a critical, data-driven appraisal of how most leaders actually achieved their position.

For starters, Pfeffer explains, the world is not a just place: advancement seems to go to the most aggressive -- he cites former MLB commissioner Peter Ueberroth’s maxim that “authority is 20 percent given, 80 percent taken” -- and the most political. The further you advance in any organization, says Pfeffer, the more politics tends to dominate.

In organizations of all kinds—from multinational corporations to small nonprofits—people generally advance through the ranks by pleasing their bosses. The link between job performance and outcomes is surprisingly, depressingly, weak.

“[A]s long as you keep your boss or bosses happy, performance really does not matter that much,” Pfeffer explains, “and by contrast, if you upset them, performance won’t save you.”

The best way to please bosses? Flattery. Lots of it. Why? “Because flattery works and is effective.” A critical component of workplace success and advancement, says Pfeffer, is “to help those with more power enhance their positive feelings about themselves.”

Leaders also tend to be self-promoting and unafraid of conflict. Funnily enough, writing in 2010 Pfeffer pointed to Rudy Giuliani as exemplifying this type of fearlessness. Also important is the ability to self-promote. “You need to get over the idea that you need to be liked by everybody and that likability is important in creating a path to power,” Pfeffer explains, “and you need to be willing to put yourself forward. If you don’t, who will?”

Pfeffer also reveals that while research shows that two dimensions most people are evaluated on are competence and warmth, these are in tension. “[T]o appear competent, it is helpful to seem a little tough, or even mean,” he writes. Yet while “Nice people are perceived as warm . . . niceness frequently comes across as weakness or even a lack of intelligence.” In contrast, he cites the example of former national security advisor Condoleezza Rice, who he notes had a reputation as someone you didn’t want to cross. Her credo: “people may oppose you, but when they realize you can hurt them, they’ll join your side.”

Pfeffer adds,

Condoleezza Rice is right; people will join your side if you have power and are willing to use it, not just because they are afraid of your hurting them but also because they want to be close to your power and success. There is lots of evidence that people like to be associated with successful institutions and people—to bask in the reflected glory of the powerful.

Sound familiar?

Pfeffer deconstructs several qualities aspirationally associated with leadership, and suggests in each case, the opposite may be true. Modesty, for example, is frequently cited as a quality leaders should exhibit, yet, he writes, evidence suggests “modesty is a rare, and possibly extremely rare, quality among leaders.” In contrast, “narcissism and narcissistic behaviors are quite common.”

According to Pfeffer,

Immodesty in all of its manifestations—narcissism, self-promotion, self-aggrandizement, unwarranted self-confidence—helps people attain leadership positions in the first place and then, once in them, positively affects their ability to hold on to those positions, extract more resources (salary), and even helps in some, although not all, aspects of their performance on the job.

Research Pfeffer cites demonstrates that “overconfident individuals achieved higher social status, respect, and influence in groups.” In fact, says Pfeffer, “the most celebrated leaders are particularly likely to be narcissistic and immodest,” and notes that “narcissistic CEOs seem to earn more compared with others in the top management team, and last longer in their jobs—probably because they are more ready and willing to eliminate their rivals.”

Pfeffer is similarly dismissive of the value of authenticity, another quality highlighted by leadership gurus. Argues Pfeffer, “the last thing a leader needs to be at crucial moments is ‘authentic’—at least if authentic means being both in touch with and exhibiting their true feelings. In fact, being authentic is pretty much the opposite of what leaders must do. Leaders do not need to be true to themselves. Rather, leaders need to be true to what the situation and what those around them want and need from them.”

What about honesty? Says Pfeffer: Lying “is positively associated with both having and acquiring power” and “a behavior that is often quite effective.”

Trust? “[D]ata suggest that trust is notable mostly by its absence,” Pfeffer says, adding, “if the violation of trust brings the violator money and power, there are essentially no consequences at all. That is because our desire to bask in reflected glory and our motivation to achieve status in part by associating closely with high-status others overcome any ill will toward those who violate trust but wind up with money, power, and status.”

He continues, “Trust-breakers for the most part retain their networks and social relationships because others in their orbit haven’t been harmed by their actions, so they don’t feel compelled to redress the harm. Few people want to fight losing causes when they have a much better alternative—making peace and cozying up to the other party.”

And if all of that wasn’t depressing enough, there’s the concept of “servant leadership.”

Read enough business books and you’ll think that great leaders put employees first. While Pfeffer acknowledges this approach seems “ethical” and also “makes business sense,” it doesn’t seem to be what most leaders actually do.

The harsh reality, he says, is that “power is positively correlated with hierarchical rank, and senior people mostly use their power to protect both their jobs and their salaries and perquisites.” He adds, “the sad fact is that when leaders mess up, they typically leave with lavish severance packages while regular employees suffer job losses and wage cuts.”

Moreover, says Pfeffer, “[r]esearch shows that leaders take credit for good company performance and attribute poor performance to environmental factors over which they have no control, to predecessors, to macroeconomic issues, or sometimes to other organizational interests, particularly frontline employees.”

We’ve seen this movie before.

To be clear, Pfeffer isn’t endorsing the behaviors he describes, nor is he suggesting they characterize every leader—or even the ideal leader. Rather, he’s trying to show that this is the brutal truth explaining how many people have climbed to power and held onto it over the years. You might not subscribe to these principles, but in life you will probably be competing against others who do.

Pfeffer’s remarkable ability to describe prospectively so many of the behavior patterns we’ve seen play out in the current administration suggest that they may be more the rule than the exception. These power dynamics, however distasteful, are almost certainly not specific to Trump or those currying his favor, but seem to exist, albeit less conspicuously, within most organizations, wherever human beings vie for influence, resources, and status.

It’s a reality that’s painful to acknowledge, but more dangerous to ignore.