How Putin Enabled Pogroms

Kremlin propaganda stoked hate—and Putin’s Chechen ally Ramzan Kadyrov cultivated a brutal brand of Islamism.

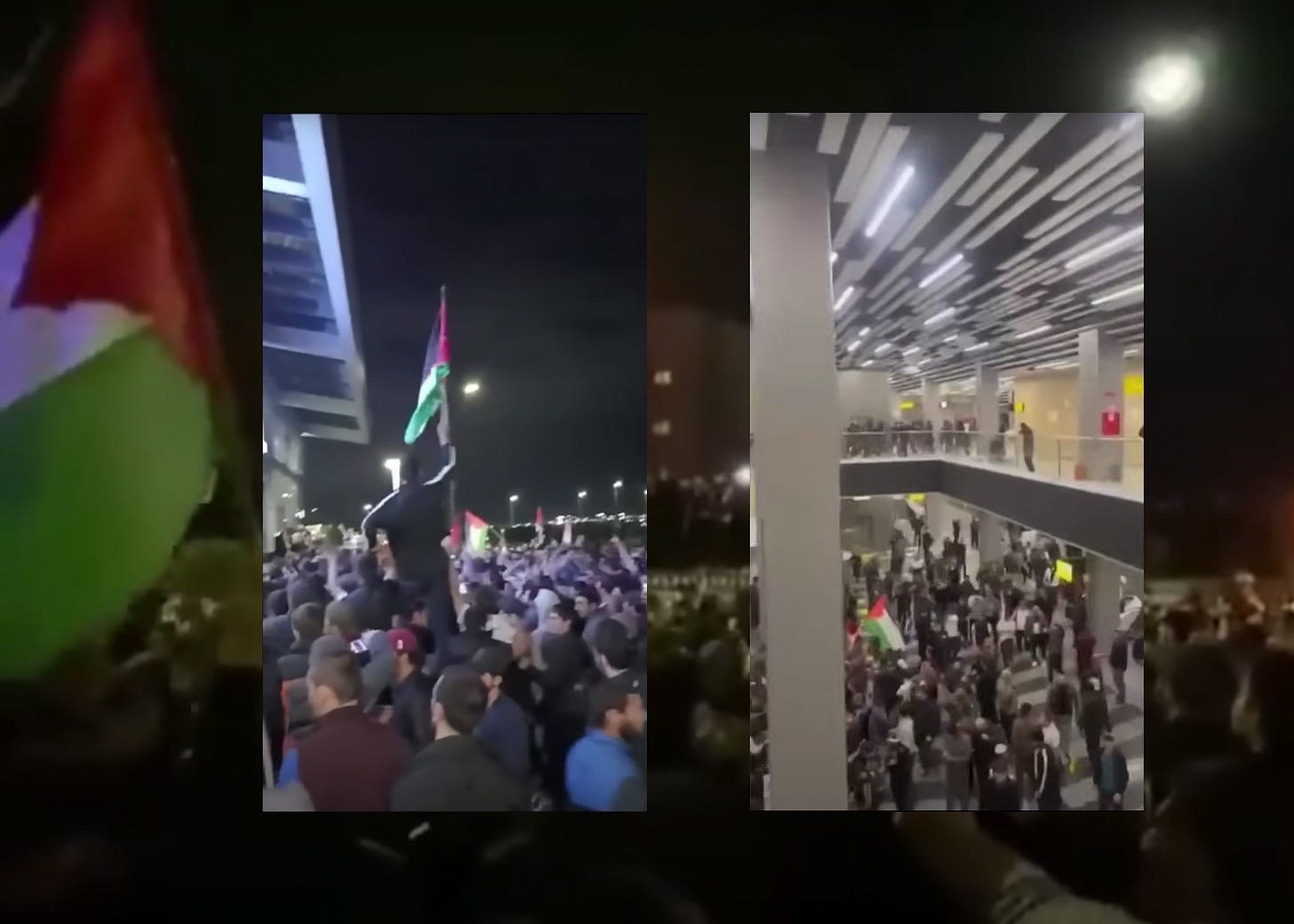

THE GENERALLY GRIM NEWS FROM RUSSIA became even grimmer on Sunday with reports of а wave of anti-Jewish violence and hate across the North Caucasus. In the worst of these incidents, an angry mob in Makhachkala, Dagestan converged on an airport in search of passengers from a just-arrived flight from Tel Aviv. Hundreds of rioters rampaged through the terminal, pelted buses with rocks, and rushed out onto the tarmac to surround the airplane. A chilling video filmed by a passenger after its landing shows people running toward the airplane while the pilot announces over the intercom: “Ladies and gentlemen, please stay in your seats and do not try to open the doors. There is an enraged crowd outside . . . it’s entirely possible that we may get trashed. So please stay seated and follow all the instructions of the flight attendants.”

Luckily, the mob’s attempt to hunt down Jews was thwarted because the Israeli passengers on board were Russian-born Jews, most of whom also had Russian passports, and because airport staff helped them hide in a VIP lounge until rescue arrived. (They eventually had to be airlifted from the terminal by military helicopter.) More than twenty people were reportedly injured in the attack and ten were hospitalized, two in serious condition—though apparently none of them was a passenger.

It took about twenty-four hours for Vladimir Putin to speak about the attempted pogrom. When he finally did, he blamed, in the least surprising twist ever, instigation by Ukraine and its “Western patrons,” specifically “the ruling elites of the USA” and other “geopolitical puppeteers.” But many observers argued that the true causes should be sought much closer to home. Dissident Russian commentators widely agreed that the Kremlin itself bore major responsibility, having cultivated hate, aggression and xenophobia with its war propaganda. As expatriate historian Tamara Eidelman put it, “If killing Ukrainians is permissible and even good, why not Jews?” Some also mentioned the recent avalanche of anti-Israel invective on Russian propaganda channels and the Putin regime’s overt flirtations with Hamas; senior figures from the terror group visited Moscow just last week and met with foreign ministry officials.

But there’s another factor: Ramzan Kadyrov, the Putin ally whom one expert calls “the Chechen thug-dictator-extraordinaire.”

A former separatist rebel in Chechnya (which neighbors Dagestan), Kadyrov was personally installed atop its government by Putin in 2007. He governs Chechnya as a personal fiefdom within Russia and maintains one of the most brutal and repressive regimes this side of North Korea. A recent report by an expert appointed by the OSCE found, in the words of the U.S. representative, that “Chechen government officials have committed serious and ongoing human rights violations and abuses with impunity, engaging in ‘harassment and persecution, arbitrary or unlawful arrests or detentions, torture, enforced disappearances and extrajudicial executions.’ Victims include LGBT individuals, human rights defenders, journalists, and members of civil society, among others.”

Kadyrov also exploits an authoritarian and brutal form of Islamism as an ideological pillar for his rule. And he is, according to political scientist and human rights lawyer Steve Swerdlow, “one of the most prominent anti-Semitic voices in the region” who has “stoked the flames of hatred over his social media for years.”1

According to ethnographer Velvl Tchernin, the growth of antisemitism in Dagestan—where a once-large, centuries-old population of “Mountain Jews” speaking a dialect of Farsi had dwindled to about two thousand in 2013 and is almost certainly smaller now, due to post-Soviet emigration to Israel and the United States—is in large part the result of influence from Chechnya, that is, from the Islamism promoted by Kadyrov and his henchmen.

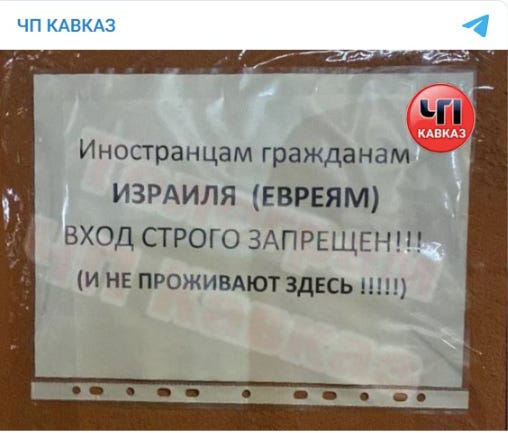

THE AIRPORT ATTACK in Makhachkala was only one of several frightening incidents of its kind. Also in Dagestan, in the city of Khasavyurt, a stone-throwing mob attacked a hotel after reports that it was housing refugees from Israel. After the rioters were persuaded to disperse, management put up a “No Jews allowed” sign.

Meanwhile, in Nalchik, in the nearby “autonomous republic” of Kabardino-Balkaria, a Jewish cultural center under construction was set on fire with burning tires tossed onto the construction site, and “Death to Yahoods” (from the Arabic word for “Jew”) was scrawled in Russian on the wall around the site. And in Cherkessk, capital of the republic of Karachay-Cherkessia, a pro-Palestinian rally 200 to 500 strong in front of the government building included demands not only that Israeli visitors be barred from the republic, but that its current Jewish residents (estimated at under thirty, out of a total population of less than half a million) be expelled.

Some regional authorities, secular and religious, have issued condemnations. The Coordinating Council of Muslims of the Northern Caucasus, a body composed of Islamic scholars, made a statement expressing sympathy for Palestinians but also declaring that “the Muslims of the Northern Caucasus cannot be on the side of hate or intolerance toward other peoples or religions.” The Supreme Mufti of Dagestan, Ahmad Afandi Abdulaev, recorded a video address urging “patience and calm,” though he also suggested that the antisemitic incidents were the result of understandable “indignation” about the plight of the Palestinians which needed to be resolved in some other way. The head of the republic, Sergei Melikov, blamed the disturbances on “provocations” by extremists and “enemies of Russia,” but also had harsh words for those who “fell for these provocations.”

Yet by the standards of Russia in 2023, where people have been imprisoned for posting anti-Putin jokes on social media or distributing antiwar leaflets, the antisemitic “protesters” have been treated quite mildly. While about thirty of the Cherkessk demonstrators who demanded the eviction of Jews from their region were arrested and charged with holding an unsanctioned rally, none are being prosecuted for incitement of hate. Neither are the airport rioters in Makhachkala. Reports in the independent media also suggest that Rosgvardia (National Guard) troops brought in to quell the disturbances took a long time to act and were not particularly aggressive; there are even reports that at one point, a police officer using a bullhorn to urge the rioters to disperse assured them that “we understand how you feel.” One obvious explanation is that the authorities and law enforcement don’t quite know what to do with “protests” that don’t concern Putin or the war in Ukraine.

Russian media have flogged the fact that some inflammatory posts about the arrival of a plane from Israel had appeared on a dissident Telegram channel, Utro Dagestana (“Dagestan Morning”) originally founded by Ilya Ponomarev, a maverick Russian politician who now lives in Ukraine. Official Russian media falsely attributed to Ponomarev an admission that the unrest was “coordinated through our Telegram channel,” although Ponomarev has said that he has not had any role in running the channel for about a year; a former Ponomarev associate confirmed this to Meduza. Meanwhile, the Russian-language Israeli website Detali (“Details”) reports that since October 7, antisemitic rhetoric in the Northern Caucasus has surged in both pro-government media and dissident online media, with an accompanying surge of hostility toward Jews. In one alleged incident, a woman who contacted the local police about receiving antisemitic threats was told, “Well, look at what you people are doing to their children over there!”

In Chechnya, Kadyrov proposed a coalition of Muslim countries that could pressure the West in stopping Israel; his Telegram post also decried “horrifying acts of Zionist genocide” and asserted that “in its cruelty toward Palestine, Israeli fascism today fully equals or perhaps even surpasses Hitler’s.” Kadyrov’s minister of information, Ahmed Dudaev, did go on television to remind viewers “aggression toward people of Jewish ethnicity” is wrong because there are many good Jews—the ones who “unequivocally condemn the criminal actions of the Israeli leadership.” On Tuesday, Kadyrov announced that he was authorizing Chechen police to use lethal force to stop “unsanctioned unrest”; however, he also stressed his endorsement of righteous anger against “the Israeli regime” while chiding those who would channel this anger into trashing airports in search of Jews.

EARLIER THIS YEAR, Kadyrov’s self-positioning as an Islamic leader and a champion of Muslims was on display in a very different context—one that did not involve Jews, but fully showcased the Chechen president’s own brand of fascism as well as his full impunity under the umbrella of the Putin regime.

On May 19, 19-year-old Nikita Zhuravel, a student at a teachers’ college in the Russian city of Volgograd, posted a video of himself burning a Koran, with the Volgograd mosque as a backdrop. He was promptly arrested and charged with “public actions. . . committed with the aim of insulting the religious feelings of believers.” Zhuravel, a Sevastopol native, confessed (make of it what you will) that he had been recruited by Ukrainian special services and offered 10,000 rubles (about $107) to burn the Koran and instigate religious strife in Russia. Appearing in court, he apologized to “all the Muslims in the world.”

On May 21, the Russian Investigative Committee made a startling announcement: Zhuravel would stand trial—and would be held pending trial—in Chechnya, in response to “numerous requests” from insulted Chechen Muslims. Most likely, the only “request” that mattered came from Kadyrov, who had, on an earlier occasion, offered a bounty for the execution of Koran-burners. On May 27, Zhuravel was brought to the Chechen capital of Grozny, where an angry crowd met him carrying signs such as “Trial by the people for the Satanist!” Some of the assembled may have gathered spontaneously, but part of the demonstration may have been organized: a May 23 rally in Grozny denouncing Zhuravel’s blasphemy was reportedly full of government employees who admitted they were instructed to attend.

Debates about blasphemy laws aside (even most Russian liberals seem to agree that deliberate anti-religious provocations like Koran-burning should be at least punishable by a fine), the change of venue was flagrantly illegal: The Russian penal code states that crimes must be prosecuted in the jurisdiction where they are committed, with a narrow range of exceptions, none of which apply in Zhuravel’s case. It also outlines change-of-venue procedures, none of which were followed. In June, Putin mentioned the move with evident approval.

The next twist in this saga was even more shocking. In late August, Zhuravel, still jailed pending trial in Chechnya, complained to Russia’s (try not to laugh) human rights ombudswoman, Tatyana Moskalkova, that he had been beaten up by Kadyrov’s teenage son, Adam. Moskalkova referred the complaint for investigation. A month later, Kadyrov himself finally commented on the allegations in a Telegram post—by confirming them and stating that he was “proud of what Adam did.” The president of Chechnya also shared a brief video that showed his 15-year-old son punching, kicking, and slapping a cowering Zhuravel. Other high-level public figures in Chechnya also chimed in with enthusiastic praise. Kadyrov’s right-hand man, Adam Delimkhanov, the head of the Chechen branch of Rosgvardia and a member of the Russian State Duma, opined that the junior Kadyrov “acted like a real man and a worthy son of his people” with “genuine determination to defend our faith and our values.” He added that “considering the heinous crime of this monster Zhuravel, Adam acted very humanely in letting him live.”

This grotesque display prompted mild expressions of dissent even from some loyal Russian politicos. Several Duma members timidly pointed out that while the law prohibits insults to the feelings of believers, offenders must be punished by law, not vigilante justice, and that allowing the young Kadyrov to rough up a prisoner was . . . also kind of illegal? Journalist Eva Merkacheva, a member of Putin’s tame “Presidential Council on Human Rights,” not only expressed dismay at the clip but urged the authorities to bring Zhuravel back from Chechnya for his safety. Her appeal was ignored.

Neither Putin nor his spokesman, Dmitri Peskov, commented on the incident. (Peskov bluntly explained his refusal to make a statement: “I don’t want to.”) The authorities declined to charge the junior Kadyrov with assault (what a shock!), citing the fact that he is a minor.

But it gets better: Adam Kadyrov’s youth did not prevent him from being awarded the title of “Hero of Chechnya” on October 6. A few days later, the intrepid young defender of the faith also received an award from Tatarstan, another predominantly Muslim republic within Russia, for “a significant contribution to strengthening interethnic and interfaith harmony and accord,” and an award “For services to the Republic of Karachay-Cherkessia,” the republic’s highest honor.

Expatriate Russian political analyst Stanislav Belkovsky argued that the sudden shower of awards for the junior Kadyrov could not have happened without the Kremlin’s approval. Belkovsky saw these developments, coupled with the Kremlin’s pro-Hamas tilt in the wake of October 7, as part of Putin’s attempt to cultivate Muslim alliances in his own war against the West. (It’s also part of a combination of appeasement and repression by which Kadyrov and Putin keep the North Caucasus terrorized and obedient.) Other sources say that Putin did not approve the awards and is not pleased, but is taking a hands-off approach.

Be as it may, the glorification of Adam Kadyrov is certainly another sign of Russia’s further slide into barbarism and brutality—and of the normalization of violence that Kremlin critics see as a factor in the recent antisemitic riots. Couple this with Kadyrov’s own status as one of the most prominent public figures in Putin’s Russia, and it all bodes ill for Russia’s remaining Jews—at least ones reluctant to show their loyalty, as in Soviet times, by ritually denouncing Israel and Zionism.

It’s worth noting that Chechnya has no Jewish community today: Virtually all of its Jewish population was evacuated to Israel in 1995 during the first of the two bloody wars between Russia and Chechen separatists.