How the ‘Big Lie’ Became a Big Threat

The window for enacting the reforms needed to protect our democracy is closing fast.

There is reason to be less sanguine today about the fate of American democracy than at the nadir of the Trump administration (pick your low point). The longstanding and cynical GOP obsession with anti-voter-access laws has mixed with Donald Trump’s Big Lie about the supposed theft of the 2020 election by Joe Biden, congealing into a Republican campaign for indefinite single-party control of American government. It might be too late to turn back toward democracy. But it’s urgent that we try.

Washington, D.C. is currently under single-party control, to be sure: Both houses of Congress and the White House are unified under the Democratic party. Single-party control of the legislative and executive branches is not uncommon—it was the case at the start of 16 of 21 first-term presidencies dating back to Theodore Roosevelt. But we might soon see a very different kind of single-party control, one that, as a result of GOP machinations, is not bound by voters’ will and other democratic constraints.

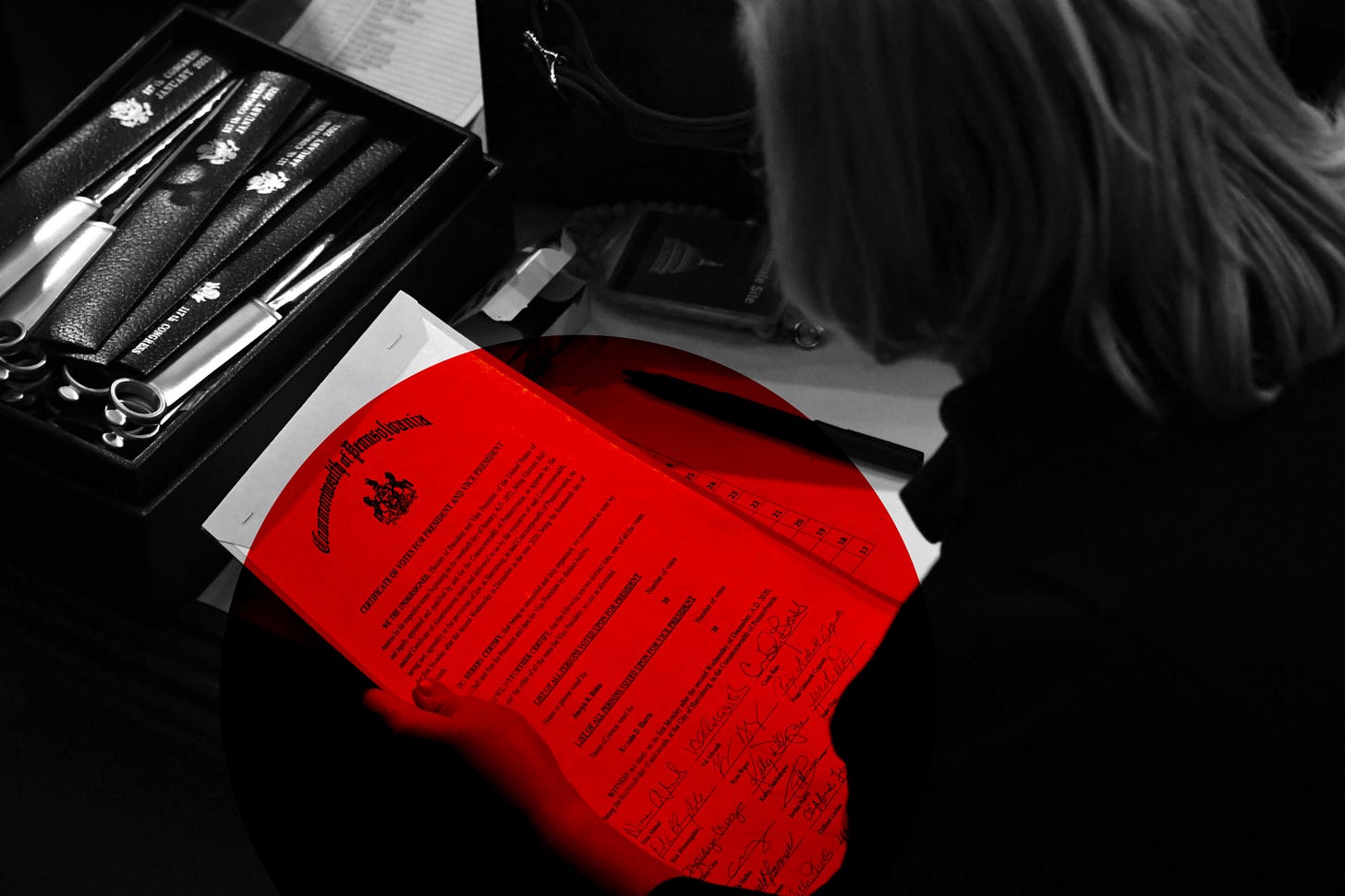

To date, there has been no meaningful political accountability for the January 6 insurrectionist attack on the Capitol. In fact, the opposite is true—Liz Cheney is expected this morning to be tossed out of her leadership spot as House Republican Conference chair for sticking with democratic principles and refusing to buy into the Big Lie. By contrast, her Trump-anointed replacement, Elise Stefanik, was one of the 126 representatives to support the bogus case brought to the Supreme Court in December by the Texas attorney general seeking to overturn Joe Biden’s victory in Pennsylvania, Georgia, Michigan, and Wisconsin. And hours after the attack on the Capitol, Stefanik voted to cancel other Americans’ duly cast votes for president.

Some might breathe easier knowing that Joe Biden made it to the Oval Office—despite 60 lawsuits, Trump’s legally suspect call to Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger seeking to “find” enough votes to swing Georgia his way, and the bloody attack on the Capitol. But no one should rest easy: The next time around probably won’t have such a happy ending. Republicans are banding together to make sure that a future president-elect from the Democratic party doesn’t make it to inauguration day.

Let’s start at the state level. Across the country, Republican state legislatures have been considering, and in some cases have succeeded in passing, laws to make it harder to vote. Fast-forward to 2024. Imagine that, despite these new barriers to the ballot, a majority of voters in, say, Georgia manages to choose a Democrat for the presidency over the Republican candidate. Republicans are preparing to reflexively reject those results. In fact, the GOP is trying to give itself multiple bites at the apple to cancel out the popular will and lock down the presidency for the losing Republican candidate.

In Georgia, the recently enacted package of election laws empowers the state assembly to elect the chair of the state election board, snatching that role from the secretary of state. Hypothetically, then, a popular vote for a Democrat in 2024 could be “adjusted” by a Republican-led legislature in precisely the manner that Raffensperger refused to do at Trump’s behest in 2020.

Alternatively, the Georgia legislature could determine that the election has “failed” under the current version of the Electoral Count Act, and pick its own Republican winner of the state’s Electoral College votes, despite a contrary choice by actual Georgia voters.

If that kind of outmaneuvering of the popular vote made its way to the U.S. Supreme Court, the conservative-tilted Court might well back the state legislature. Conservatives on the Court, including Justices Samuel Alito, Clarence Thomas, and Neil Gorsuch, have already signaled an openness to interpreting the relevant constitutional language (“each State shall appoint, in such Manner as the Legislature thereof may direct, a Number of Electors”) as absolute—that is, that only legislatures can fix rules relating to presidential elections, not state courts, secretaries of state, or other election officials who are delegated related powers by statute or otherwise.

To complete the coup, if the true Electoral College vote managed to survive the state legislature in December, a Republican-controlled Congress could kill it during the vote-counting on January 6, 2025. In its current form, the Electoral Count Act allows a single senator and a single representative to object to a state’s certification on any grounds, as we all saw on January 6. If, as a result of objections to a state’s slate of electors, no presidential candidate has an Electoral College majority, the selection of the next president is thrown to the House, where each state votes as one. Republicans would presumably win such a vote; even now, with Republicans in the overall minority in the House, they have majorities in a majority of the state delegations.

This prospect that the presidency might be purloined by Republicans—that “the real steal is coming,” as Mona Charen puts it—is reinforced by other anti-democratic factors. The Republican-dominated successes in gerrymandering of congressional boundaries to effectively silence state majorities that want change, and Trump’s successful use of the COVID pandemic to enjoin census workers from completing their work in 2020, led to a net gain of Republican seats in the House and additional heft in the Electoral College—without a single vote being cast. Let’s not forget, too, that the conservative-dominated Supreme Court endorsed both of these maneuvers by banning any political gerrymandering case from seeing the light of day in court and upholding Trump’s halting of the census count.

The end result is a further shift away from democracy. Our Constitution is not a document that adheres to principles of a direct or pure democracy, of course; federal judges are unelected and serve for life, the presidency is chosen by slates of appointed electors, and laws are made through representatives. But especially notable in this regard is the composition of the U.S. Senate: It is structurally disproportionate to the voting public, with two senators per state, and that disproportion has become much more extreme over time. In 1790, the smallest state, Rhode Island, had a population about a tenth the size of the most populous state, Virginia. Today, the smallest state, Wyoming, has a population about one seventieth that of California—but they have equal representation in the Senate. This imbalance means that voters in rural states have a much greater say in the Senate than city-dwellers, who tend to vote Democratic. According to an analysis by Ian Millhiser, even though the Senate is evenly divided between the two parties, the fifty Democratic senators represent 41.5 million more people than the fifty Republican senators.

To put it another way, for Republicans, the Big Lie works as a singular platform because Trump voters in rural locales exercise disproportionate power in the Senate, which, in turn, won’t pass election reform, presumably because it would hinder the Republican minority’s ability to stay in power.

The Senate’s structure cannot change without a constitutional amendment—an all but implausible scenario, since it would require two-thirds majorities in both houses of Congress and ratification by three-quarters of state legislatures. Statehood for Washington, D.C. and Puerto Rico would alter the balance of power by adding four senators, but that can only happen with ten Republican votes in the Senate under the filibuster, a procedural relic that virtually ensures minority veto power over any policy choice of the majority.

The filibuster also insulates the Electoral Count Act from much-needed reforms, such as clarification that state legislatures cannot ignore the popular vote when certifying their respective Electoral College votes in December of an election year, and that Congress cannot ignore the state certifications on January 6 of the following inaugural year.

Again, our Constitution is not a simplistically democratic charter. But its small-r republican features depend for their legitimacy on its small-d democratic features. When the democratic imbalance in our Senate is as bad as it has become, and when one powerful party is hellbent on subverting the electoral process to snatch future elections from actual voters based on lies about a past election and through laws that discourage voting, our political order is nearing its breaking point. If reforms are not enacted, and quickly, we face the loss of our constitutional system’s legitimacy and our democracy itself.