How the Fight for Women’s Suffrage Was Won

100 years ago today, the U.S. secretary of state confirmed that the Nineteenth Amendment—granting women the right to vote—was the law of the land.

Suffrage Women’s Long Battle for the Vote by Ellen Carol DuBois Simon & Schuster, 383 pp., $28

During the centennial celebration of the American founding in Philadelphia’s Independence Park on July 4, 1876, a small band of women led by Susan B. Anthony unexpectedly took the stage. “I present to you a declaration of rights from the women citizens of the United States,” Anthony stated firmly as she thrust a sheet of parchment into the bewildered hands of Vice President Thomas Ferry. Her mission accomplished, she and her companions stepped off the podium to attend a rally at the opposite end of the square, where Anthony read a copy of the document aloud to an eager crowd. Among the numerous “articles of impeachment” that the declaration detailed stood “Universal Manhood Suffrage,” which, by “establishing an aristocracy of sex, imposes upon the women of this nation a more absolute and cruel despotism than monarchy; in that, woman finds a political master in her father, husband, brother, son.”

Anthony’s protest in Philadelphia is just one of many powerful moments that UCLA historian Ellen Carol DuBois describes in Suffrage. Drawing on her background as one of the preeminent scholars of women’s history in the United States, DuBois deftly compresses the seventy-year struggle for female voting rights into a lucidly written volume that is essential reading as the nation celebrates the centennial of the Nineteenth Amendment this year.

Although Suffrage is largely a work of synthesis, it offers a vital argument countering contemporary claims that the campaign for suffrage was advanced solely for the benefit of white women. DuBois presents suffrage as a movement that was both deeply intertwined with other social justice causes—such as abolition and workers’ rights—and propelled by an incredibly diverse cast of women. However, like the Revolution that birthed the United States, the fight for women’s political equality suffered from setbacks, moral failures, and internal quandaries that dulled the sheen of its triumph on August 26, 1920.

DuBois is unafraid to acknowledge that the Nineteenth Amendment left much work unfinished, but her book is an important reminder of the powerful obstacles that suffragettes faced in their bid for the vote. There is little reason to believe that suffrage was inevitable. DuBois makes it very clear that the belief in keeping women in a childlike state of legal dependence upon fathers and husbands for the sake of social stability was one that, in the words of suffragette Ida Husted Harper, “died hard.” Perhaps that’s because the vote was necessary to secure the liberal notion, in the words of Anthony’s declaration, that “woman was made first for her own happiness, with the absolute right to herself.” If there is a subtext to the struggle for the vote, it is the tension inherent to a movement that required women to work as a collective to assert their right to live as individuals.

Suffrage opens with the 1848 Seneca Falls Convention and the drafting of the Declaration of Sentiments, one of the earliest political documents articulating the need to correct women’s second-class social, economic, and political status in the United States. There DuBois introduces us to Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Anthony, whose “friendship was one of the most important working partnerships in American history.” Cady Stanton brought a fearsome intellect and vision to the burgeoning women’s rights movement, complementing Anthony’s masterly ability to organize campaigns and coordinate resources on the ground. They were the first of many dyads of friends, mothers, daughters, and rivals that shaped the movement through its various stages.

Both Cady Stanton and Anthony also came from families involved in anti-slavery activism, and DuBois underlines the significant overlap between abolitionism and the women’s rights movement. For example, Frederick Douglass attended the Seneca Falls gathering and forcefully argued in favor of including a resolution to secure women’s suffrage in Declaration of Sentiments. A few years later, at another women’s convention in Ohio, Sojourner Truth sharply underscored the multiple layers of oppression that black women faced on account of their race and sex. And when the Civil War erupted, Cady Stanton and Anthony launched the Women’s Loyal National League, America’s first political organization created by women, for the purpose of collecting anti-slavery petitions (which would help support passage of the Thirteenth Amendment). Cady Stanton and Anthony also worked with Douglass and Lucretia Mott to create the American Equal Rights Association, a group that fused abolitionist and women’s suffrage circles to pursue universal suffrage and equal political rights for all Americans after the war’s end.

DuBois carefully explains how the debate over the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments led to a terrible rupture in this otherwise natural alliance. Believing that the passage of the amendments would be indispensable for protecting newly freed slaves from Southern violence, black feminists like Douglass and Frances Ellen Watkins Harper backed both amendments even though they excluded female suffrage. Disappointingly, some suffrage leaders (including Cady Stanton) began espousing racist, classist, and nativist rhetoric as they lamented the enshrinement of male privilege in the Constitution. While DuBois never excuses this response, she contextualizes the profound betrayal felt by many women’s rights activists on account of this omission and the unresolved racial oppression that forced former allies of women’s suffrage to make difficult compromises. In her nuanced portrayal of the thorny social and political realities that faced early suffragettes, DuBois demonstrates historical writing at its best.

To compound this setback, it is at this juncture that the women’s rights movement itself split into two factions: the National Woman Suffrage Association, led by Cady Stanton, Anthony, and Isabella Beecher Hooker, and the American Woman Suffrage Association, led by Lucy Stone and her husband, Henry Blackwell. NWSA restricted leadership to women and encouraged them to protest by voting in defiance of local law. The group also furthered attempts to locate a women’s right to vote in the existing Constitution, with members brilliantly but unsuccessfully arguing that Section 1 of the Fourteenth Amendment implicitly included universal enfranchisement as a protected “privilege” accorded to American citizens. AWSA, on the other hand, allowed men and women to participate in its leadership and focused on building tightly run associations across the nation that could methodically advance support for women’s enfranchisement at the local level. Although each organization had misgivings about the other, they represented the twin forces of radical action and gradual reform that are necessary for enacting lasting political change.

Although it’s difficult for DuBois to avoid wrapping her narrative around the activities of famous suffrage leaders like Cady Stanton, Stone, and Anthony (whom she especially seems to admire), Suffrage is studded with the contributions of women from all walks of life who joined the fight for the vote. For example, DuBois introduces her readers to Rose Schneiderman, a Jewish immigrant from Poland who argued that suffrage was critical for improving workplace conditions for women so that there would never again be tragedies like the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire, which claimed the lives of over one hundred (mostly female) garment workers in 1911. She also highlights the voice of anti-lynching activist and investigative reporter Ida B. Wells, who criticized the movement’s willingness to cater to the interests of Southern suffragettes instead of actively denouncing the campaigns of racial terror in the Jim Crow South.

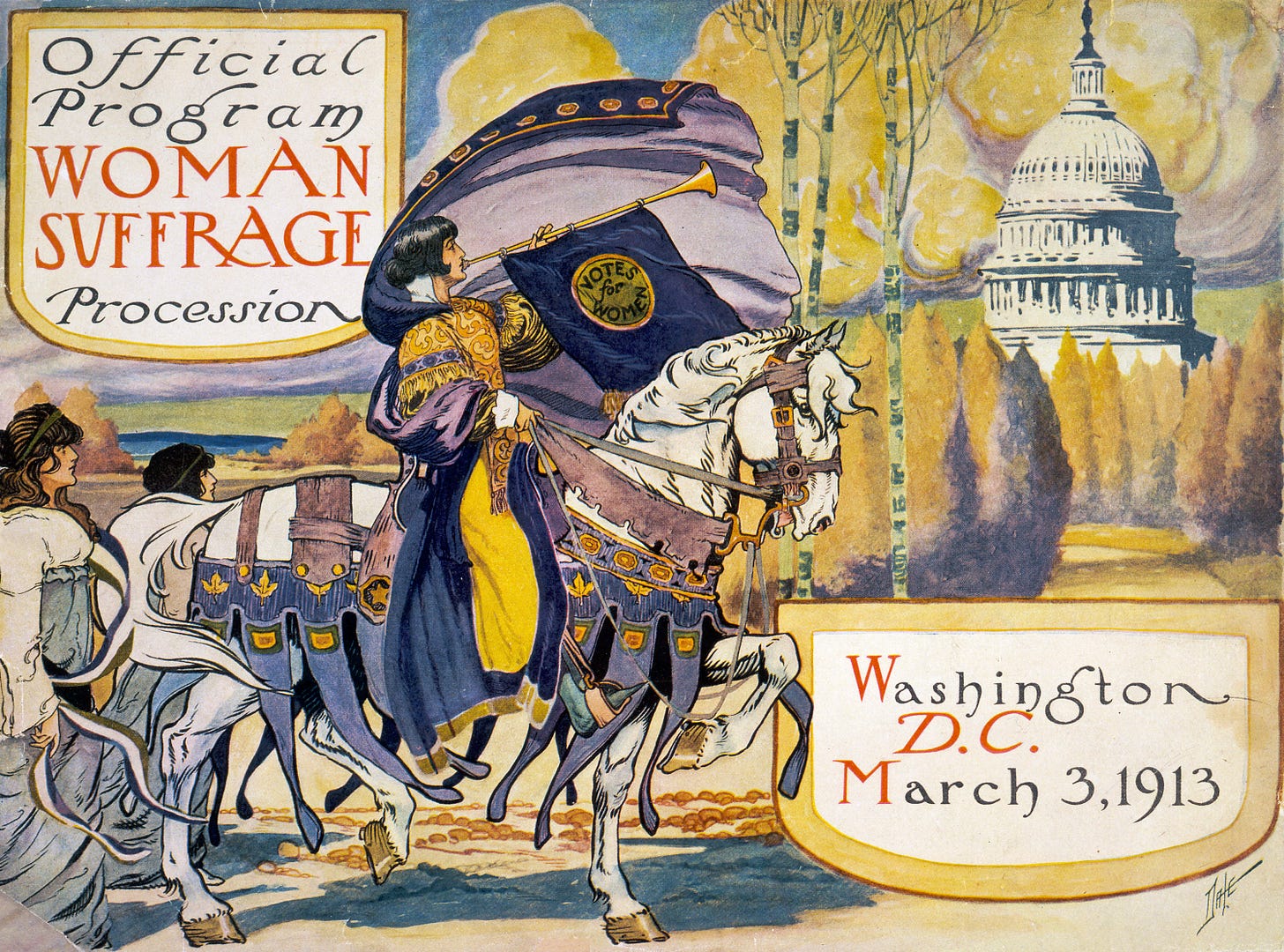

Schneiderman and Wells formed a part of the following cohort of women who drove the suffrage movement through the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. DuBois notes how this period marked the dawn of the “New Woman,” who pushed against circumscribed female roles by pursuing college degrees and economic independence. Alice Paul was a chief exemplar of this new breed, assuming NWSA’s visionary mantle by founding the Congressional Union for Woman Suffrage (later reformed as the National Woman’s Party). While older suffragette Carrie Chapman Catt took control of the National American Woman Suffrage Association and carried on the AWSA’s bolstering of local organizations, Paul and the younger feminists who formed the bulk of the NWP organized defiant parades, campaigned energetically against politicians who opposed suffrage, and endured imprisonment and hunger strikes for picketing the White House. “Suffragists had been appealing to the public’s reason with very limited results,” DuBois explains, so “this new generation went for the emotions: excitement, attraction, desire.”

Although DuBois clearly views Paul’s bold activism as essential to driving public enthusiasm for female voting rights, she demonstrates special appreciation for women who won battles for the vote through conventional, but no less arduous political campaigns. Suffrage shines when recounting in detail the tenacity of local women who helped to initiate the slow wave of state amendments granting the vote in Western states. But the most gripping moment in DuBois’s book is her exploration of the multi-year crusade to secure such an amendment in New York. Although suffragettes endured multiple crushing losses, they always rebounded, adapting their tactics to convince a larger swath of voters (a task that relied heavily on outreach efforts by black women) and cleverly navigate Tammany Hall’s control of the political landscape. When New York finally passed a suffrage referendum in 1915, Catt aptly called it the “Gettysburg of the woman suffrage movement.”

Success in New York convinced Congress that there was sufficient national support for suffrage to seriously consider an amendment to the Constitution. In her final chapters, DuBois again highlights the importance of skillful lobbyists like Helen Hamilton Gardener, who quietly cultivated relationships with senators, representatives, and even President Woodrow Wilson to generate support for the vote, and Ada James, whose years of working with politicians in Wisconsin enabled that state to be the first to ratify the suffrage amendment in 1919. And in the end, it was a gentle request from his mother that convinced a 24-year-old legislator to cast the deciding ballot in Tennessee securing ratification in August 1920.

If Suffrage makes anything clear, it’s that the long road to political equality for women could not have been walked alone. The opposition was too fierce and too cruel. It is painful to read of the politicians who angrily denounced the threat of “petticoat rule,” the men and boys who sexually harassed women as they marched in streets across the nation, the anti-suffragettes who internalized and regurgitated canards of women’s mental inferiority and unsuitability for politics. Contemplating the widespread ridicule and ire that the mere suggestion of female autonomy once aroused is deeply unsettling, especially when it seems that such contempt has never completely gone away.

The suffrage movement succeeded because, paradoxically, it sewed a wide tent out of this perverse denial of female individuality. It counted among its members women (and many men) of almost every race, creed, and marital status. It’s why DuBois’s cast of characters includes socialists and wealthy socialites, college students and former slaves, conservative temperance activists and liberal advocates for free love. As a result, the unity of purpose it engendered would not survive the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment. Not only did the amendment fail to adequately protect voting rights for black and Native American women, later attempts to create a single organization that could somehow comprise the interests of all women failed precisely because they rejected the emphasis on individuality that had given the women’s rights movement its greatest strength.

It is important to keep this tension in mind. Enfranchisement was never supposed to be a panacea for all the problems of womankind. But it was the foundational tool allowing women to fully assume the responsibilities of citizenship in a democratic republic. The “strongest reason” for emancipating women, Cady Stanton noted in one of her final public addresses, “is the solitude and personal responsibility of her own individual life. . . . Who, I ask you, can take, dare take on himself the rights, the duties, the responsibilities of another human soul?”

Cady Stanton’s unequivocal emphasis on female self-reliance is perhaps disorienting, especially knowing that her work to advance women’s rights depended on her partnerships with others. But perhaps Cady Stanton’s life, like the lives of many of her fellow activists, offers a challenge for our own time. As we embark on the next century of suffrage, women should ask ourselves how we can use our votes not just to secure our own particular vision of happiness, but that of our sisters as well. We do not need to treat politics as the zero-sum game that once emboldened men to deny women their place in the political arena, convinced that their votes were at best superfluous and at worst dangerous to the social order. With every accusation we lob at each other for voting “against women’s interests,” we participate in the same pernicious denial of individuality that dogged suffragettes for decades.

Like the champions for female voting rights who found the keys to their emancipation in our nation’s founding documents, we should recover ownership of the opportunities for pluralism that our political structure affords us. We should do our best assume the difficult, but important work of carving out space, solidarity, and support for both the female entrepreneur and the stay-at-home-mom; the woman in the boardroom and the woman behind the lunch counter; the pro-life volunteer at a pregnancy clinic and the trans women seeking protection from discrimination. It would be the greatest tribute we could pay to the generations of women who hung together, however imperfectly, to become masters of their own fates and captains of their own souls.