How to Destroy the Republican Party

Just do the popular stuff. This isn't rocket science.

1. Popularity Contests

538 has launched its global tracker on Joe Biden’s job approval. Here’s what we look like one week in:

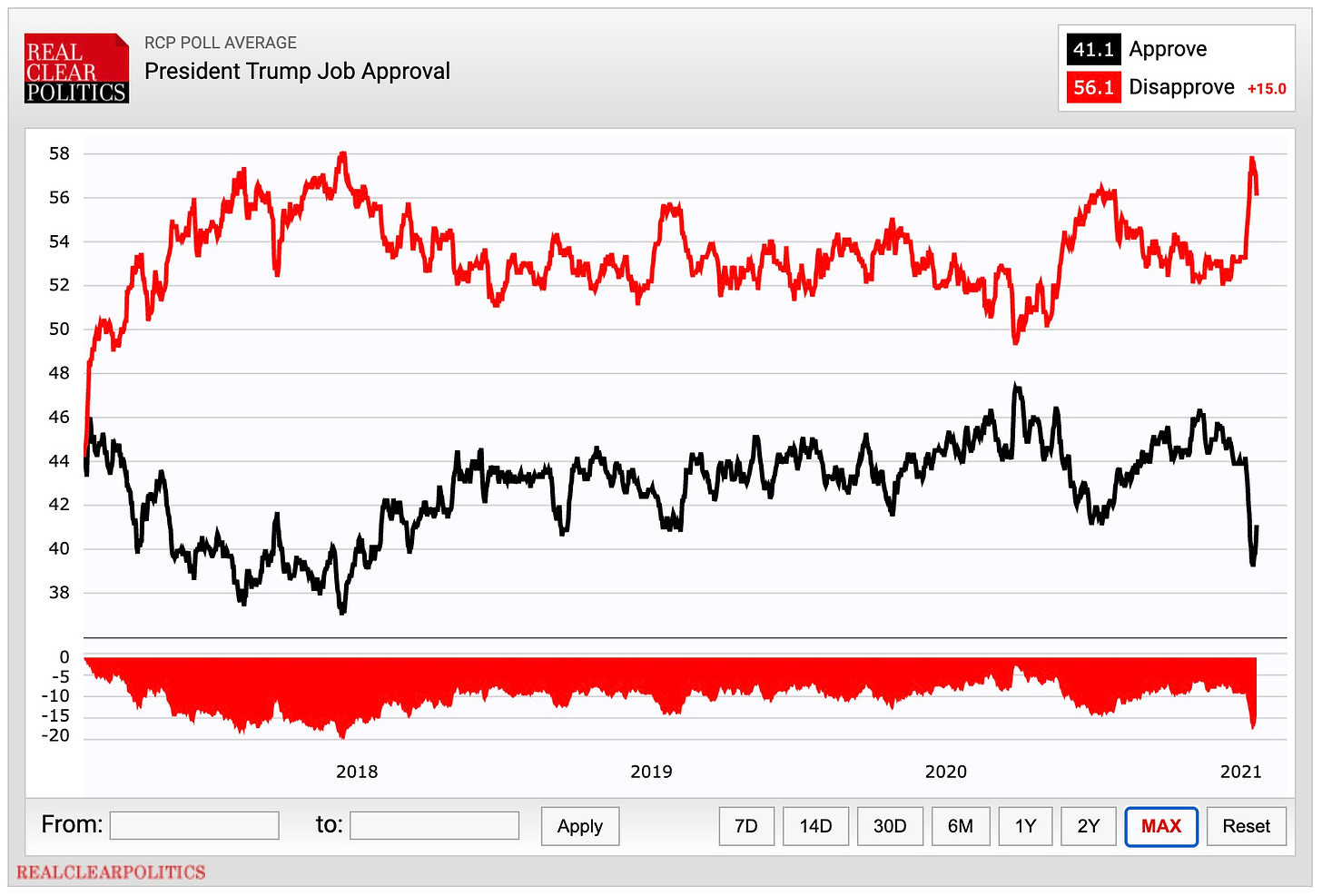

I know what you’re thinking: It’s 7 days. What’s the big deal? Well I want to remind you of what the Trump administration numbers looked like:

By January 29, 2017, Trump was already net -1 on his job approval. Why is that?

Well, here are some headlines from that first week of the Trump administration:

Trump pressured Park Service to find proof for his claims about inauguration crowd

Trump would favor Senate rule change if Supreme Court choice blocked

That last one, by the way, is about Trump calling for the end of the filibuster should Democrats “obstruct”—his word—his Supreme Court pick.

Because Republicans have always been so concerned about the sanctity of Senate traditions and the essential nature of the great and good filibuster.

The reason for this quick backward glance is twofold.

As a reminder of how consistently unpopular Trump’s presidency was with the public.

As a cautionary tale for the Biden administration.

Democrats have a pretty substantial opportunity right now because there are large chunks of their agenda that are broadly popular. Biden will succeed or fail as a president in large part because of his willingness to prioritize the broadly popular parts of the Democratic agenda and back-burner the issues that appeal more narrowly to Democrats.

What should that look like? Well, here are some numbers:

79 percent of voters favor another round of COVID stimulus.

Between 60 percent and 70 percent favor a robust democracy reform package. (The number depends on which elements you include.)

Close to 70 percent are in favor of a public option.

Boom. That should be Biden’s phase one legislative agenda, right there.

There are other issues, which are deeply important to Democrats but either do not have broad appeal outside their caucus or have broad appeal only in specifically limited circumstances.

For instance, infrastructure spending is popular—but only when accompanied by tax hikes on the rich, which gets into dangerous territory.

And there are some elements of climate-change legislation that have broad support—planting trees, giving tax credits to businesses that control emissions, restricting power plant emissions. But there are elements that are deeply unpopular, such as a gas tax and encouraging the use of nuclear power.

Putting aside the merits—there are strong arguments for both the gas tax and nuclear power—it will be important for the Biden administration to be hard-headed about the opportunity costs.

Or, to put it another way:

The administration has a 12-month window to pass legislation and any item they take up—even a policy with 60 percent public support—will require a brutal fight with congressional Republicans and a disciplined, rigorous approach to rallying public opinion.

They should not spend a single minute of this precious time fighting on any ground that isn’t immensely favorable to them from the start.

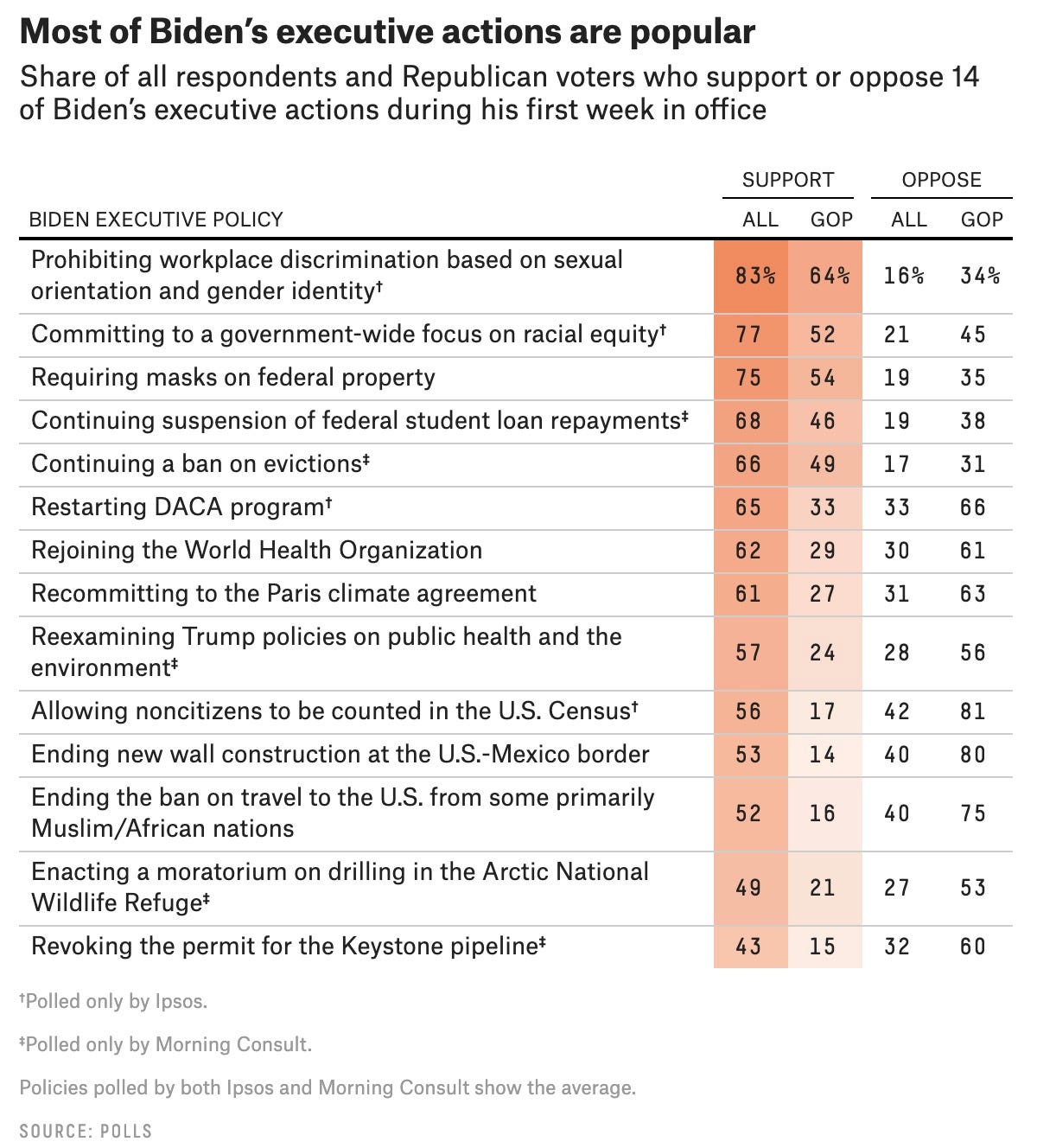

The good news is that I think Biden gets that. 538 took a look at the polling on his first batch of executive orders and it was mostly encouraging:

Mostly good. But not all. Look near the bottom of that list and you’ll see how Biden could get himself into trouble: ANWR and Keystone XL are firmly in the danger zone. The Muslim ban and the immigration measures (wall and census) are dicey—the kind of actions that you can probably get away with so long as you’re ready to aggressively frame them for the public.

But you can also see how a dug-in Republican party could turn them into liabilities.

Here is the ugly truth about Joe Biden’s first term:

His absolute top, overriding goal must be keeping Republicans out of power in 2024. The GOP is now a quasi-authoritarian party, which has demonstrated that it is not only willing, but eager, to overturn American democracy.

Everything Biden does should be in service to this one, overarching goal.

And that means being relentlessly focused on popularity and opportunity costs. It simply isn’t enough to say, “Well, Policy X may not be popular with everyone, but it’s a big priority for Democrats and we won, so we ought to see if we can bring the public around.”

Too much is at stake for that kind of sentimentality.

Stick to the popular stuff. Relentlessly make the case for these policies to the public.

Oh, and one more thing: If Democrats decide that they are intent on killing the filibuster, don’t do it in the abstract. Find the most important and broadly popular issue available, turn it into a piece of legislation, and then nuke it from orbit after Republicans obstruct from the wrong side of public opinion.

Voters care about policies, not process.

And popularity matters.

Big live show tonight at 8:00 p.m.

We’re trying to make this a regular thing for Bulwark+ members and I’m pushing for Thursday Night Bulwark as the genius branding idea. These shows are insanely fun, kind of like Firing Line, but with your friends, at a bar.

And the episodes are archived so that members can watch them any time, in case they can’t make the live show.

2. GameStop

I said most of what I have to say about GameStop and the untethering of the finance sector from value on Tuesday.

But what has happened since then is that some people are trying to turn this into a story about the powerless versus the powerful, like it’s some kind of Boston Tea Party. And I think that’s a deep misunderstanding.

My buddy Ranjan Roy of the Margins (Subscribe! It’s free!) has a pretty good explainer as to why this narrative is wrong:

I'm happy for anyone who made the trades, took some profit, and is taking a breather. For everyone else, please stop reveling in this weird, convenient narrative of a bunch of Gen Z'ers hanging out on Reddit shaking up the establishment. Yes, there will be guys with amazing usernames posting gain porn. Yes, the NYT will find laid-off line cooks who are up 1600% and quote them saying "It's crazy".

But if you really believe this is about a bunch of 'little guys' taking on 'Wall Street' and the 'establishment', I'll assume you also believed Donald Trump was going to take on the establishment and drain the swamp, or something. . . .

I am not a "Wall Street" supporter. I left bank trading exactly because I was uncomfortable with how stacked things felt against everyday people and the financial crisis cemented my view. A big dream of Informerly (the defunct personalized news startup that I spent four years working on) was to curate information from the financial blogosphere and finance Twitter for a wider investor base (and yes, for professionals too #KillTheBloombergTerminal!)

In fact, if a decade ago, you told me there would one day be some reddit-driven financial market battle against Wall Street, it would've been my dream. But that is not what's happening. . . .

What is happening is that some guys on Wall Street are losing and some guys on Wall Street are winning:

As Ranjan observes:

Oh, and of course, Blackrock would make money on this. And the vulture-like private equity fund Sycamore. And a couple of Chinese billionaires.

So yes: If you’re reading this and you’ve made a few bucks or a few million bucks on GameStop, God bless you. I hope you treat yourself to a car with Russ Hanneman doors.

(Don’t forget about taxes.)

But you should also understand that this sort of action is bad for the macro economy. Here’s Ranjan again:

A few years ago, I wrote a piece about Tourist Money, a term coined by Mohamed El-Erian about inflows into emerging markets. El-Erian described a phenomenon common in emerging markets - where a bunch of foreign capital rapidly makes its way into a hot market, completely distorting the internal economics of the nation, and then, at the first sign of trouble, bails.

I wrote my senior undergrad thesis on how Malaysia, during the Asian Financial Crisis, implemented capital controls to prevent money from going in or out. At the time, the IMF, along with most others, economic orthodoxy stated that any kind of restriction on capital was a bad thing. After better understanding the human cost of what happens the capital suddenly skips town, I argued that Malaysia was justified. . . . Fast, hot money has been a problem in emerging markets that has often resulted in severe economic catastrophe.

Well, the tourists have landed on our shores. But this is not some American family in Italy in the late 90s with fanny packs looking for a McDonald’s. This is a legion of British football [Thanks for not calling it soccer -Can] hooligans hitting some Central European town, pissing on your doors, and throwing empty glasses at you while harassing your girlfriend. And when the fun is over, the tourists will leave. And they'll leave quickly.

There will be costs to this. Human costs. Workers will get screwed. Some of the retail investors will get screwed, too. But the big one is that this is another data point in how American financial markets are beginning to act more like emerging markets—which is not good.

Being the backstop of the global economy is boring and normal and also confers the kinds of enormous, built-in advantages that are invisible right up until the moment they disappear. Kind of like the advantages to being the world’s reserve currency of choice.

Nihilism never leads to good outcomes. Not in your personal life. Not in political life. And not in economics, either.

This story doesn’t have a happy ending.

3. AT Trouble

Uh-oh. No one tell Sarah:

You should have seen my legs the night I finished the Appalachian Trail. Standing naked in front of a half-length mirror in a Maine hotel room so dingy and dated it should have come with complimentary mothballs, I marveled at what I had become over the past 2,200 miles. I was now a rippling sheet of endlessly lean muscle, my sinew bulging beneath mud-caked skin like some surrealist relief map of the ancient ridges I’d walked. David might have looked this ripped, I mused to myself euphorically, had Michelangelo wielded a better chisel.

There was, however, a twinge of irritation. Although my wife, Tina, and I had transformed our bodies into aerobic-exercise automatons over the past five months, becoming more fit than we’d ever been, we’d have to wait to run—she’d broken a toe during a day off, with 600 miles to go, while I had broken one three days before the summit of Mount Katahdin and the end of the AT, when a root in the 100 Mile Wilderness ripped through my trail-tattered shoe. Our brief stints in medical boots would provide a chance to rest and recover. It was only late August of 2019; I assumed we’d be ready for marathon medals and astounding PRs by the winter season.

I’ve never been more wrong: the 17 months since we scrambled down the junkyard-like boulder field of Katahdin’s south side on broken toes and in obliterated shoes have been a seesaw between enthusiastic exercise and a forlorn state of inactivity, connected by varying levels of chronic pain and, consequently, depression. I have not raced at all. Instead I have become a willing ward of the health care system, trying to figure out why, exactly, my parts don’t work or recover like they did before we sprang north from Springer Mountain, Georgia.