How to Draw Nothing

Nick Drnaso’s much-anticipated graphic novel ‘Acting Class’ leaves everything to the reader’s imagination.

Acting Class by Nick Drnaso Drawn & Quarterly, 248 pp., $29.95

Halfway into Nick Drnaso’s newest graphic novel, Acting Class, a protagonist named Thomas passes a woman in a hallway. She’s unfamiliar to the reader; maybe Thomas knows her from his modeling job. He smiles at her, and she smiles back. Then he stops smiling.

The interaction occurs over five panels. The woman’s expression gets a full panel to itself—as if to say, remember this face. Thomas has already had a rough evening, and now, after exchanging glances with this woman, he’s clearly unwell. He tells his boss he can’t pose nude anymore; he’s “suddenly uncomfortable.” He looks down in silence when his boss asks him why.

The woman does not appear in the novel again.

What could it possibly mean?

According to Drnaso’s harshest critics, not much. He’s bad at drawing faces; the eyes simply can’t convey what the reader needs to know. Even his favorable reviewers, including a New Yorker writer privy to early drafts of Acting Class, have described his artistic evolution the way a parent might congratulate a toddler: “The white people were no longer all the same color. . . . Some of them even had mouths, and were using them to smile.”

But read any interview with Nick Drnaso, and you’ll find that his harshest critic is Nick Drnaso. Just before publishing his 2018 graphic novel Sabrina (to massive, unprecedented literary acclaim, including the first Booker Prize nomination ever given to a graphic novel), he grew so disgusted with the manuscript that he appealed to his publisher not to release it at all—agreeing to let publication go forward only after they allowed him to make substantial, ninth-hour edits. One imagines him in his Chicago apartment redrawing the panels, perfecting them again, despising them again, and so on—scouring each over his lightbox like a radiologist looking for occult fractures. “I draw with so few lines,” he says, “that every line counts.”

Wait—look. The woman’s face. The line of her mouth curves downward, in fact. It’s only the cleft of her upper lip that made the expression seem a smile.

Ah. So she’s upset with him. But why? Does she know something the reader doesn’t? Something serious? After all, Thomas, with nine other protagonists, has been spending evenings with a self-proclaimed acting guru whose exercises draw out tendencies we wouldn’t have expected from the mild-mannered Thomas—tendencies he insists aren’t really his—manipulative, thieving, even dangerous tendencies. But that’s all acting, right?

These questions, the reader may realize, are Thomas’s. He’s losing it. Paying too much attention to a stranger’s resting face. The woman means nothing, and that is the point. A narration box might’ve spared us the effort—“Since playing a killer in last night’s acting class, Thomas feels accused by the eyes of strangers,” or something—but instead, Drnaso leaves us to solve a puzzle that isn’t even there, until we recognize his characters’ paranoia by feeling it firsthand.

Or, we breeze on by and forget the woman ever existed. After all, five panels can be read in two seconds, even if it took Drnaso two days to draw them.

This is the gamble of literary fiction: that the reader will slow down, reread, put in their own work. Dig around in their own life for the insights the author needs to make his story mean something. Nabokov: “Up a trackless slope climbs the master artist, and at the top, on a windy ridge, whom do you think he meets? The panting and happy reader.” Panting, because we’re the ones who’ve had to construct an imaginary world according to someone else’s exacting specifications, using only our distracted senses and a scrap pile of memories. But happy: We’ve built a world. It’s ours too, and whatever senses it borrowed, we’ve gotten them back heightened. Or, we’ve thrown the book against a dorm room wall and posted a 1-star review on Goodreads. It’s a gamble for us, too.

But the literary graphic novelist’s ante is the highest. An artist may spend years drawing a novel that the reader can kill over a lunch break. Even Chris Ware, one of the most acclaimed graphic novelists of our time (and a fellow Chicagoan who champions Drnaso’s work), second-guesses whether the investment is worth it. In Ruin Your Life—Draw Cartoons!, he warns away would-be cartoonists: “A mediocre writer can get away with a few well-placed details to set a scene; you, however, must draw everything.” A picture is more work than a thousand words, but takes far less time to read. “Also, normal people do not read comic books.”

From the Paris Review, Issue 210, Fall 2014

And, historically, why would they have? Normal people don’t want to have to explain why they’re reading a comic book, with its WHAMs and POWs visible from halfway across the breakroom. But on a closer look, the normies would find that comics have changed. In the 1970s and ’80s, underground anthologies edited by the likes of Art Spiegelman and R. Crumb made room for new kinds of comic artists—like Harvey Pekar, Kim Deitch, Julie Doucet, and Ware—who expanded the form’s boundaries by contracting them to the mundane. Readers could now expect to see their “normal,” non-heroic lives reflected in comics, just as in the canon of literary fiction. (Or as editor Sam Leith put it in 2007, “We’re now at the point when depressed men doing nothing are as much a comic-book cliché as superheroes.”)

If “drawing everything” is hard, what these artists actually do is harder: draw absence, i.e., draw nothing. When Ware’s eponymous character in Jimmy Corrigan: The Smartest Kid on Earth sits in a hospital lobby with his sister, waiting to learn whether their dad will succumb to the injuries of his car accident, the scene’s weight lies in what isn’t depicted. Grief, blame, regret—we see none of it. Time passes. Footsteps are heard, then aren’t. Someone’s shoveling snow outside. Readers may find this lull foreboding, or frustrating, or may misattribute relevance to every movement and sound (hospital waiting room, check), or may remember the weird stillness that accompanies moments like these, when one can’t do anything to advance the plot but sit tight, notice a yellowing leaf in a lobby plant, and wait for the next page.

From Chris Ware's graphic novel Jimmy Corrigan: The Smartest Kid on Earth (Pantheon Books, 2000)

Ware calls this kind of comic “a colorful piece of sheet music.” Meaning: imbued with rhythms, recurring themes, harmonies, rests. Also meaning: It won’t play itself. The reader has to decide how long to stay in this lobby scene before turning the page, how much attention to pay to the mousy flits of Jimmy’s eyes and to the tearfulness—or shocked silence—or, wait, sleepiness?—of his sister. Glance at the page, and you’ve gotten the drift; pause on each panel, and you’ve sat with the characters.

No matter that the faces are unimpressively drawn. “The question is just how much information you can put into a face and still have it work as that inverted mask, the link to a reader’s empathy,” Ware says, implying that a character’s face works best as an invitation, with the main event being the reader’s emotional response to it—or, even, their failed attempt at one. “Occasionally I’ll deliberately put the reader on the outside of a character, because there are moments in life when one feels that way either toward others or toward oneself.” Though, Ware adds, “It’s something I rarely do.”

Drnaso does it often. In Sabrina, his characters process violent, tragic loss with the expressive capacity of stick figures. “Adding more detail to make someone seem more human isn’t necessarily effective,” Drnaso explained to an interviewer; he had just shown them a drawing of a character’s face that he had originally rendered with a clear, even dramatic expression, but then abstracted into a cipher. Teddy, boyfriend to the murdered Sabrina, spends much of the novel with his face literally blank—hidden behind his hair, sometimes, and other times, just undrawn.

From Nick Drnaso's graphic novel Sabrina (Drawn & Quarterly, 2018)

And yet a reader would be forgiven for misremembering a wince of pain always on Teddy’s face. Or for feeling haunted by the images of Sabrina’s gruesome death, which Drnaso also excised (urgently) from his final draft—why does it feel as if they’re still there? All that remains is a blue-lit staircase leading down to an apartment, evidence tags scattered upon the carpet, and a gray twin bed with its covers given a vague topography by some misshapen thing beneath them.

The “thing” is never shown, and so it can’t be looked away from. The reader’s imagination puts the body in the bed, makes it Sabrina, then disfigures her to match the uneven lumps in the fabric. When a police detective lifts the covers to see for himself, his expression tells us nothing: two period-dots for eyes, a parenthetical nose, an underscore for a mouth. In the next panel he gains an eyebrow; it’s tilted. Sorrow, maybe. Seeing Drnaso’s characters in pain is like listening to the low whine of a pet whose owner won’t be coming home—whatever sorrow we find there may be our own projection, but it’s all the more real to us, for that.

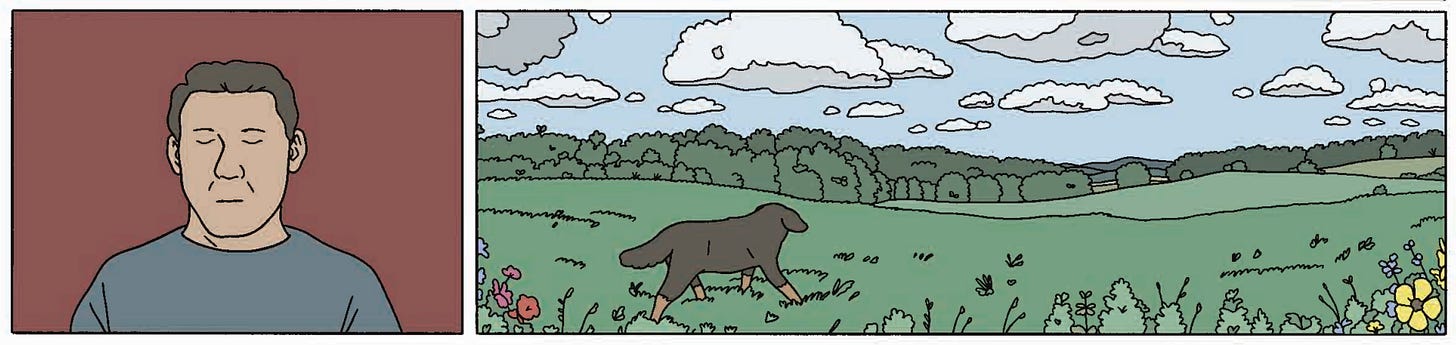

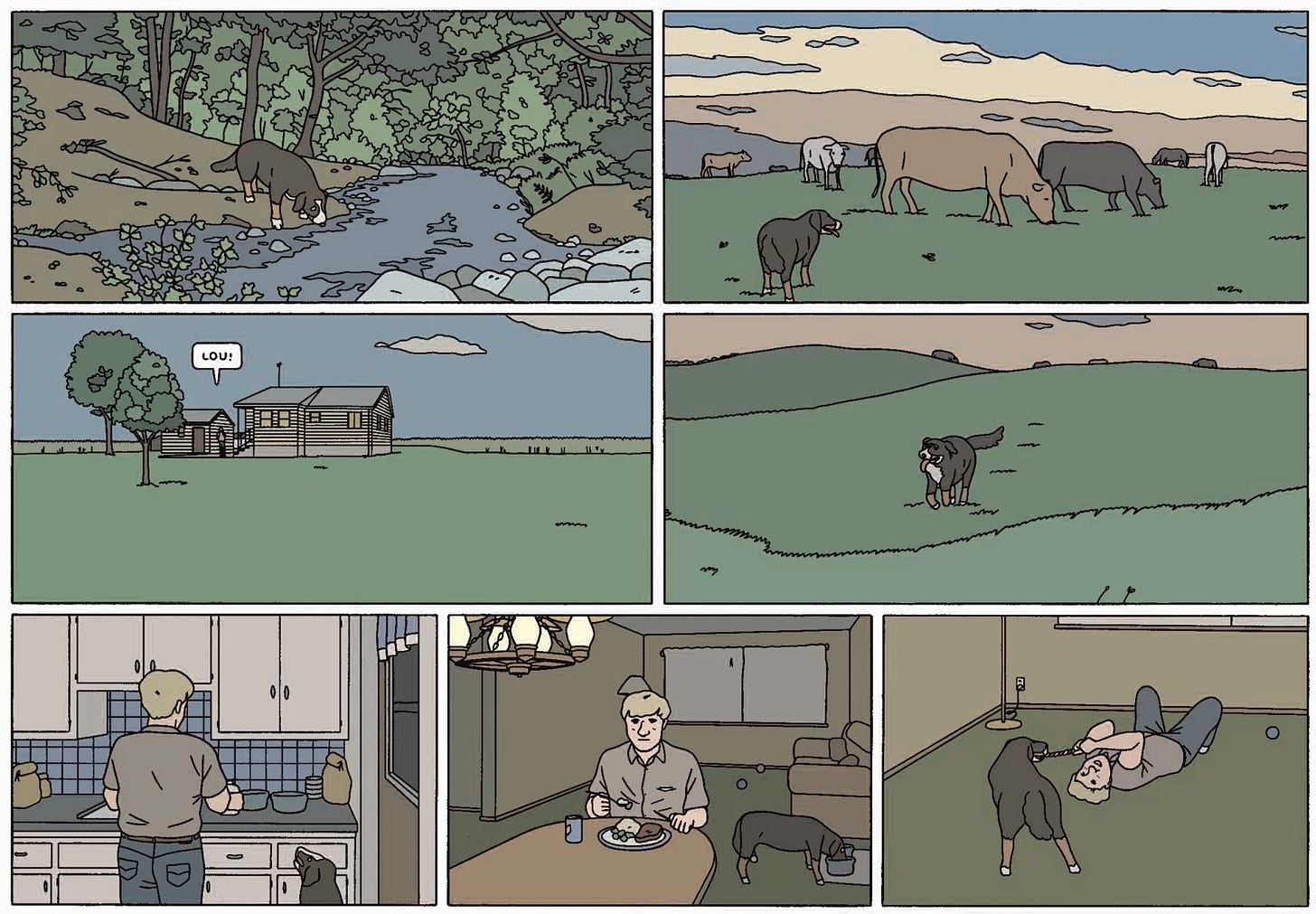

Acting Class’s most moving character is hardly developed at all: Lou, a warehouse worker who bakes chocolate chip cookies for colleagues who don’t eat them, and who pulls his pants down a little too far at the urinal, and who dreams of being (literally) a left-behind pet—but who doesn’t speak more than a handful of sentences in 267 pages.

With details this scarce, it’s fascinating to read how reviewers have summarized him: “Lou, a gym rat nursing modern masculine neuroses.” (He does appear in a gym, once.) Lou, who “takes refuge in” acting exercises (maybe, but why, and from what?), and who sets himself apart as a “keep fit” sort of guy (is he really less lumpy than anyone Drnaso draws?). One reviewer calls him friendless, as if any of the characters are shown to have real friends. In the end, Lou’s character remains opaque as an inkblot, and just as inviting of psychological projections.

The same could be said of Acting Class as a whole. Reviewers have argued that it laments the inescapability of neoliberal reality through its exploration of white mediocrity, or that it warns of the dangers of blurring fact and fantasy in contemporary politics, or in contemporary social media,or in contemporary, well, acting classes. And all this despite Drnaso’s admission that he was too anxious even to talk to any actors, let alone research an acting class firsthand, and his insistence that he doesn’t consider himself a critic of the social media era. (Technology appears in Acting Class only once, in a rural hotel room, imagined by a character during an improv exercise—and it’s a rotary telephone.) Politics make no recognizable appearance here, nor do gender dynamics, racial tensions, or class divides. (Most of Drnaso’s characters are working class, but it’s hard to see how the novel would function differently if they hadn’t been.) The story takes place outside history; it’s as bare of fixtures as the classrooms where its characters meet to make up whatever reality suits their hopes or fears.

And so, each reader’s preoccupations become their access points into Acting Class. Only a reader already attuned to social anxiety of the sort that Thomas experiences as he passes that woman in the hallway is likely to sense it there. Same for the moment when Gloria, the fretful guardian of Beth (her psychologically fragile great niece), improvises a fairly blatant scene in which she has sent Beth to an inpatient psychiatric facility. Drnaso doesn’t draw attention to the fact that Beth is in the classroom, watching; only readers keen to such discomfort (poor Beth, how humiliating!) will keep an eye out for Beth’s reaction and find that Drnaso has met them, as Nabokov would say, in the moment she next appears—

—hidden behind a support beam, near the edge of the panel. She’s been cut off—an unnerving hint at her mental state. One long scene later, she’ll find herself sequestered in an actual facility. She’ll still be playing her part, on her own, seeing meaning where it may or may not be.

As will readers. Some will meet Drnaso halfway and find deep meaning in Acting Class. Others will wonder if they aren’t doing more than their fair share of the work. What if Drnaso is just bad at drawing faces? Dennis and Rose, two class members stuck in a stale relationship, are awfully hard to tell apart, and while this may succeed in the sheet-music sense (to identify one, the reader sometimes has to find the other on the page and compare, helplessly reinforcing a stuck together characterization), it’s also pretty annoying after a while—tempting even the faithful reader to wonder if they haven’t just been looking for patterns in the emperor’s new clothes. And whatever plot hunches one has in the first half (will the acting guru’s absurd power be explained by hypnosis, druggings, occultism, or some Lynchian combination?) are unlikely to feel confirmed or denied, or even really addressed, in the end.

The faithful reader. After all, the more “nothing” an author leaves behind for us, the more faith it takes to keep following that trackless slope up to meet them—and the more it stings, when we finally summit and find ourselves alone. In an interview published four months after the release of Acting Class, Drnaso admitted he may not have gotten the faces quite right: “Maybe it did require a bit more than I put into it. Sometimes you can get lost when you’re not getting that immediate feedback from a reader that the characters look too similar.” Surely there was someone available to ask along the way? Or is Drnaso just being his own harshest critic, again? He fesses up about the acting guru, too: “Even after drawing 260 pages, I still haven’t settled what his grand purpose is.” The reader, having come to Acting Class to co-create a world, may have to finish this one on their own. The panting, unhappy reader.