How USAID Helped Us Defeat the Iraqi Insurgency

Its projects reinforced our military efforts, and served American interests while saving and improving lives.

I’M A BIG FAN OF USAID. Many senior military officials are. Anyone who actually knows what that agency does, or who has seen or benefited from what they do, likely feels the same way. I’ve seen our soldiers and military benefit from USAID’s work—not to mention millions of people around the globe.

It is a fascinating government entity. The U.S. Agency for International Development was established in 1961 by President Kennedy to coordinate disparate foreign assistance programs and organizations under one umbrella. Its mission is to give help to partners and allies who are recovering from man-made or natural disasters, whose nations are trying to escape poverty, disease or oppression, or nations that are seeking to democratize, reform, or otherwise support U.S. national interests. More than 10,000 people work for the organization—about 7,000 of those overseas in the five bureaus of Africa, Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean, Europe and Eurasia, and the Middle East. In 2023 they were provided about $44 billion in funds to execute their work, which is about 1 percent of the federal budget.

I first got the opportunity to watch USAID work up close and personal in 2007, when I deployed to Iraq as commander of the 1st Armored Division as part of the “surge.” My mission set, which came from my boss, Gen. David Petraeus, was to prepare our 30,000-strong American force to conduct counterterrorism, counterinsurgency, and security operations in Iraq’s four Arab and three Kurdish provinces in the northern part of that country. I was also charged with incorporating our Iraqi security force—consisting of five divisions of Iraqi “jundi” (about 40,000 soldiers) and 30,000 officers of the fledgling Iraqi Police—into our operations. We had fifteen months to destroy multiple terrorist networks, quash an insurgency, and leave behind a secure, self-reliant Iraq. It was the hardest assignment I ever received.

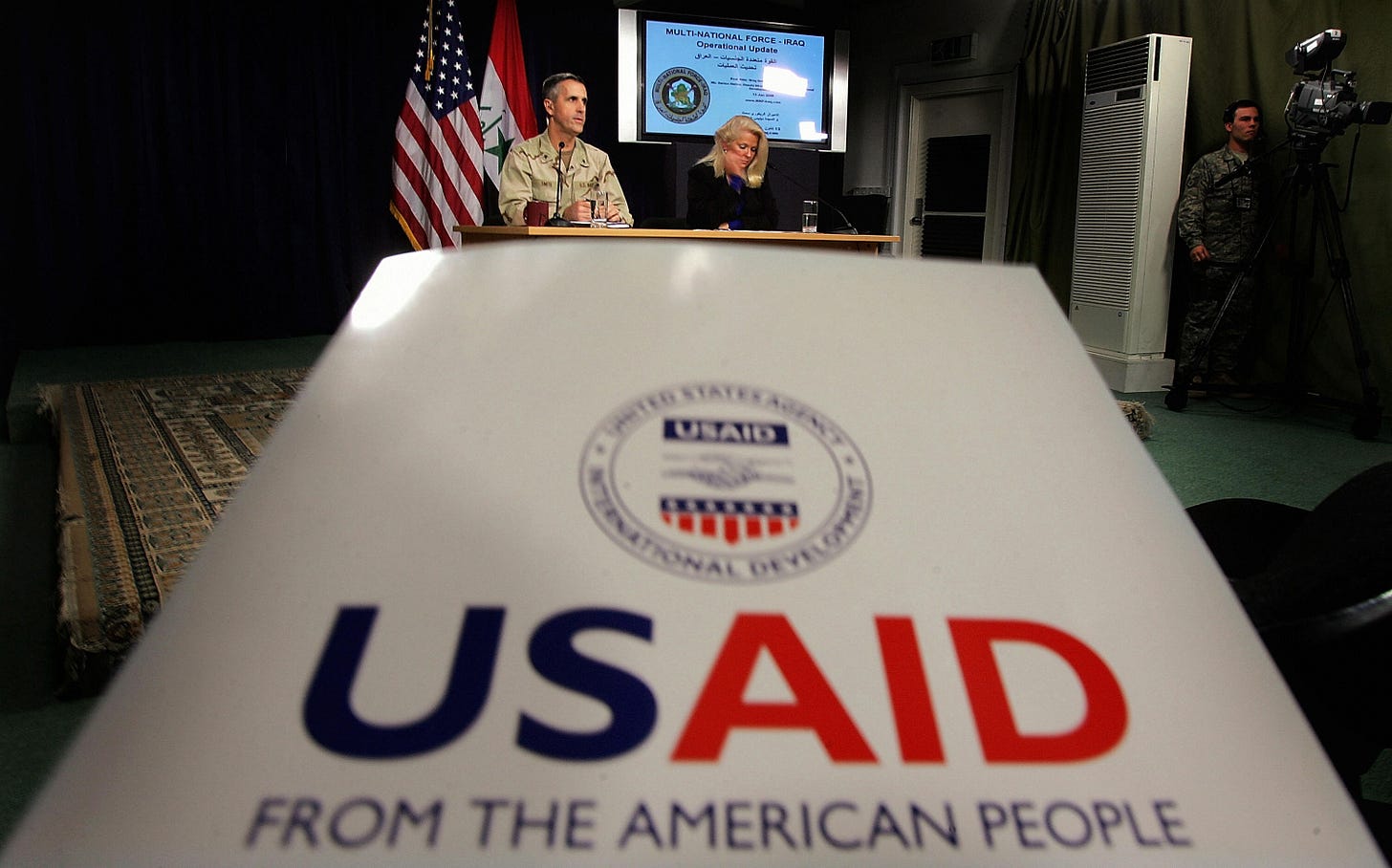

We couldn’t succeed just by killing bad guys. A key part of our mission was engaging with various Iraqi governors, mayors, and police chiefs, helping them support the Iraqi government in Baghdad and defend the security of their population. Supporting local government and crushing the insurgency meant helping the Iraqis develop a more stable economy and legitimate local governments. We were grateful to have four State Department Provincial Reconstruction Teams (PRTs) in the Arab provinces and one Regional Reconstruction Team (RRT) for the three Kurdish provinces working with us. USAID was a key part of those PRTs and the RRT—in many ways, the key part. They offered food, rebuilt infrastructure, provided medicine, and oversaw economic development with no strings attached, building trust and good will that the military alone never could have.

Northern Iraq is the size of Pennsylvania, with a population exceeding 19 million, and with religious, linguistic, tribal and ethnic differences that make the differences between U.S. states seem trivial. Our task force was a capable and ready fighting force, but our mission called for skills beyond lethality—skills beyond our military culture.

What I found in the PRTs and the RRT was true expertise in building relationships and support. The State Department foreign service officers and USAID partners all volunteered to come to Iraq during the early days of the conflict, because that was their professional ethos. They had conducted their equivalent of a human and cultural terrain analysis to determine the challenges, needs and requirements of the Iraqi people and their government at the local and national level, and they were building on their early successes even while the terrorists and insurgents were still attempting to thwart their progress. My conventional warfighters of the 1st Armored Division and our special operations partners knew plans, operations, intelligence-gathering, and how to fight bad guys while protecting citizens. But in a counterinsurgency or counterterrorism environment, winning trust and confidence of the local citizens and the support of the government required a partner.

Although the USAID mission was led by civilians and focused on humanitarian aid and economic development, their work contributed significantly to our security mission. We synchronized our work with theirs as we endeavored to “clear, hold, and build” in Iraq. By improving essential services and local governance, USAID reduced the “grievance gap” that insurgents and terrorists had exploited. As citizens began to see even slight improvements in governance and economic activity, they became less receptive to the insurgent narrative. That, in turn, indirectly contributed to our successful military mission accomplishments. In effect, using the counterinsurgency approach of “clear, hold and build,” our task force and our Iraqi soldiers and police could focus on security (“clearing” insurgents out) and stabilization (“holding” areas to prevent the insurgency from returning), confident that our USAID partners could then “build” the necessary civic capabilities to sustain long-term peace.

USAID conducted hundreds of projects to help stabilize Iraq and turn it into a security partner from 2007 to 2009. A few examples illustrate their value:

After the clearing and holding of what had previously been terrorist and insurgent strongholds in Diyala Province (the farmlands north of Baghdad that are considered the breadbasket of the Middle East), USAID brought agricultural experts from Texas A&M University known as “Team Borlaug.” This team introduced crop varieties, training, and extension services while spending extensive field time helping Iraqi farmers build greater agricultural capacity. A similar project run simultaneously contributed to more effective and efficient irrigation as well as advancements in soil reclamation. By building trust with local farm communities, our military forces also garnered significant intelligence about terrorist movements from those working the fields, including intelligence on the networks planting improvised explosive devices that were used against U.S. and Iraqi forces.

Just north of Tikrit, Saddam Hussein’s hometown and a hotbed of the insurgency, terrorists were smuggling oil and gas out of the damaged Baiji Oil Refinery. In partnership with the administrator of that facility, USAID provided reconstruction efforts to repair and reestablish critical oil infrastructure. After the war, reports from the special inspector general for Iraqi reconstruction detailed how USAID played a major role in the repair of the Baiji-to-Baghdad pipeline, while also providing information on actions of Al Qaida in Iraq.

While most of USAID’s projects focused on repairing and modernizing critical infrastructure that had been damaged by the U.S. invasion in 2003—roads, water, sanitation, electricity grids, telecommunications, etc.—they also sponsored projects to stimulate local economies through microfinance, small business development, and vocational-training programs. Given the unemployment rate of men ages 18–24 was over 60 percent when 1st Armored Division began their deployment, these projects and programs were critical to preventing the youth of Iraq from being coopted by the terrorists and insurgent networks. These essential services improved the Iraqis’ quality of life while also reinforcing the image of a functioning, responsive government after the fall of the former Baathist regime.

Was it expensive? Between 2003 and 2011, USAID invested $6.6 billion in Iraq. (By comparison, the Pentagon estimates it spent about $712 billion in Iraq in the same period.) Their programs were closely coordinated with our military commanders and staff, and this coordination was key to a strategy that combined military-security operations with civilian-led reconstruction and governance reforms. It made a difference. Ultimately, these all contributed to a significant reduction in violence and a more favorable environment for long-term democratic and economic development.

WAS THERE WASTE? Yes, as would be expected in such a herculean rebuilding of a war-torn country. But in partnering between our State Department colleagues, USAID staff, and military planners, we developed increasing draconian processes that analyzed and evaluated the approval and execution of the many projects. Those who were closest to what we called “effect-driven operations” understand stewardship and take seriously the charge to not waste government funding.

The examples from my last time in combat over a decade ago amount to just a snippet of what the selfless women and men of USAID do all over the world. Since I’ve worked with this agency, I have continuously been impressed with what they do in exhibiting America’s values. It’s fascinating to me that Americans who, a few weeks ago, could not define what USAID does, and many Republicans who wholeheartedly supported USAID in the past, are now on the side of a very few wishing to tear the organization apart.

Those who have seen the actions of USAID in support of economic development, technical and medical assistance, relief from disaster and poverty, the protection of human rights, and the invigoration of democracy know the true value of this organization to American interests and how it represents who we are as a nation to millions of people around the world who see our shining light on a hill.

To hack apart this vital arm of American soft power like a side of beef without a proper assessment of the harm it will do will diminish our standing in the world over the long term—and it will also rob our military of critical partners the next time we need them in tough situations.