In Defense of Meme-ing Edward Hopper

The case for why we are, in fact, all like lonely paintings now.

There are precious few comforts in a time of pandemic and many of the ones we have—alcohol, videogames, carbs—are bad for you. But at least we can still laugh. A few weeks ago, a meme began to circulate lamenting that “We are all Edward Hopper paintings now.” It was charming. The Guardian ran an essay by Jonathan Jones celebrating the sentiment. But no. ARTnew’s Alex Greenberger decided to be the joy police and insist that even this small comfort was bad because it wasn’t totally accurate.

Both sides of Hopperdämmerung are a little bit right and both are a little bit wrong. We are once again in a fight over taking something literally, instead of seriously. I, for one, am pleased simply that people found another era of painting to latch onto other than the Renaissance.

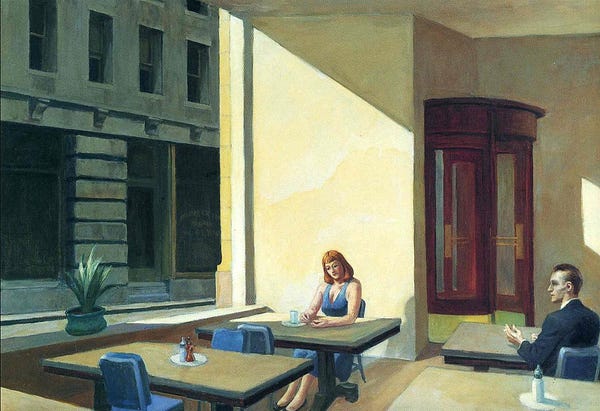

But the Jones essay arguing that we’re now living in Hopper World is hyperbolic and uneven. “The loss of direct human contact we’re agreeing to may be catastrophic,” he writes, “This, at least, is what Hopper shows us.” That’s a bit melodramatic. Hopper does not show us catastrophe. His paintings are neither sudden, nor dire. And even when they do portray suffering, it is not the monumental kind associated with the apocalypse. This can open the door to larger philosophical questions about the nature of loneliness as a disaster in and of itself, which has been brought on by the stratification of modern life. And, of course, the economic standstill caused by people having to stay home is a catastrophe. But again, that is not what we see explicitly in Hopper’s work.

So Greenberger is right to argue that the meme is a sentimental misinterpretation of Hopper.

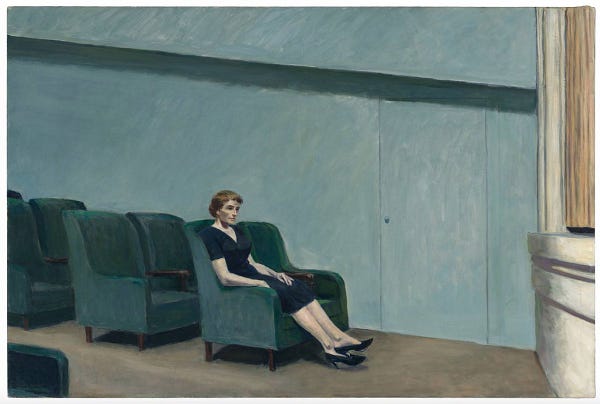

But he goes too far in dismissing the meme altogether. He says that because of the disparity in scale and since “Hopper’s subjects in stasis were actually always somewhere in the middle of a slow-motion action,” their depicted melancholia does not apply to the now perpetually home-bound. His reasoning is that since Hopper’s characters are able to leave and go about a normal day beyond the scene in which they’re shown, their solitude isn’t really anything like ours.

Jones concluded his piece by saying that “We choose modern loneliness because we want to be free.” To which Greenberger responds:

[T]herein lies a difference between Hopper’s forlorn subjects and so many of us right now. They choose to live in modernity and find themselves alienated because of it. We choose to simply try to stay alive in the world today and a pandemic that has so far killed more than 36,000 worldwide is keeping us captive.

This hypersensitivity on the question of agency is a bit contradictory. People have made the choice to abide by the dramatic measures being employed by local governments to slow the spread of the virus. The government doesn’t have the means to enforce at scale the measures they are telling people to practice. The stay-at-home orders are largely being observed voluntarily. It is not the virus that is holding us captive but—depending on how you choose to look at it—either the failure of the American government to properly prepare or the communal sense of solidarity which has led us to make the choice to stay in.

Furthermore, Greenberger’s view that Hopper’s subjects’ possess a freedom beyond the planes of their paintings might itself be viewed as somewhat sentimental. To suggest that Hopper’s subjects were “lucky” to be able to experience the suffocating nature of isolation out among the many who contribute to their sense of alienation is merely one imagined possibility.

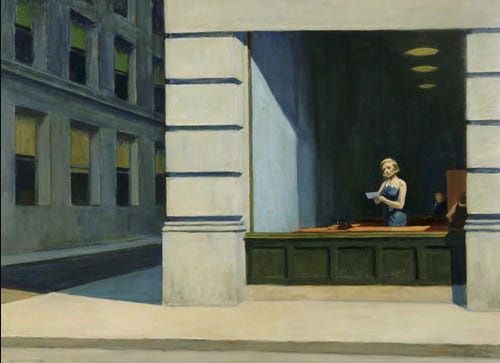

So no, Hopper’s paintings are not specifically catastrophic—but they do give a sense of the aftershocks of loss and have a heavy sense of grief about them. What we see in them is the result of some greater tragedy. In interviews, Hopper claimed to only be trying to paint himself, rather than some larger scheme of capturing American ennui. Olivia Laing writes of Hopper:

“If the statement I declare myself in my paintings is to be taken at face value, then what is being declared is barriers and boundaries, wanted things at a distance and unwanted things too close: an erotics of insufficient intimacy, which is of course a synonym for loneliness itself.”

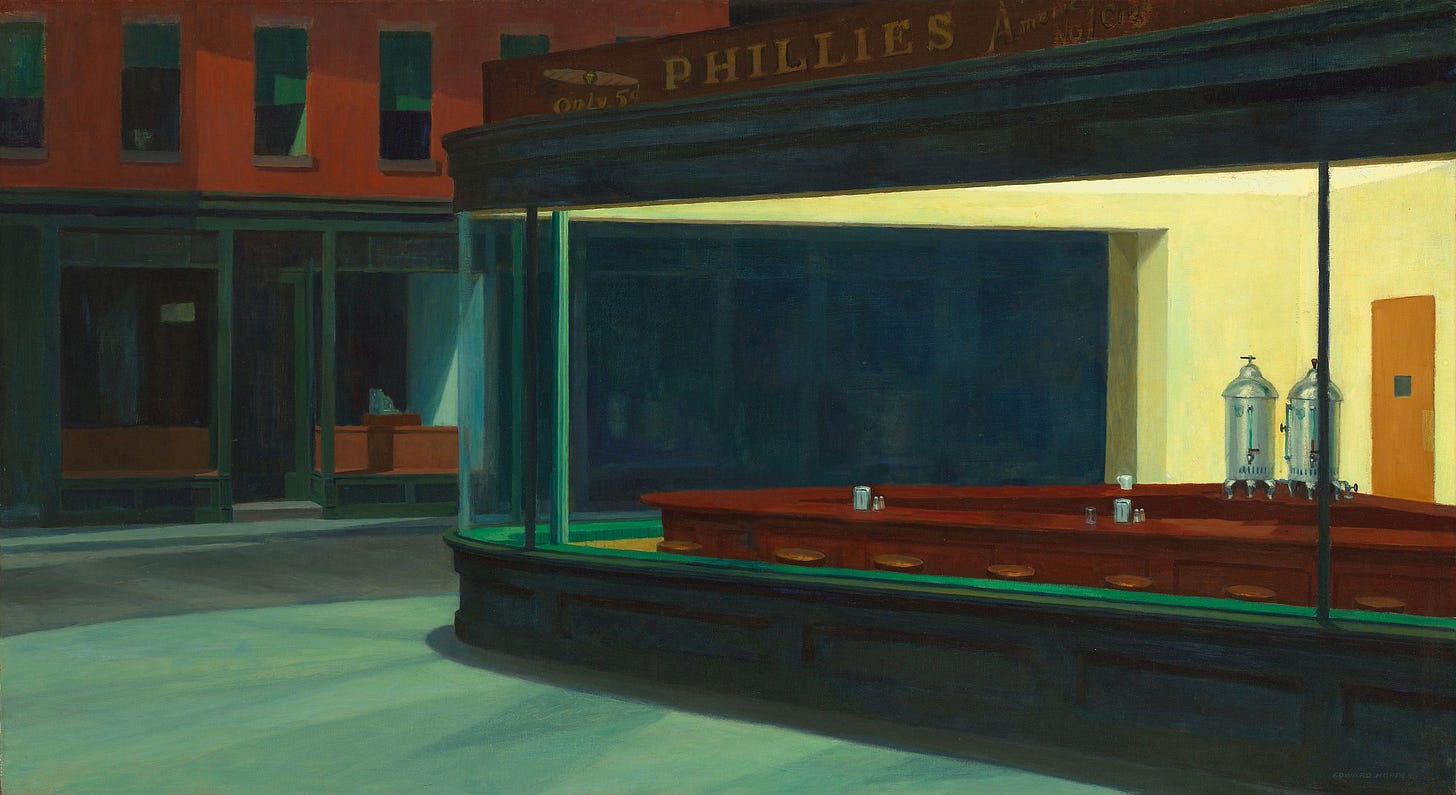

Of Nighthawks, Hopper’s most iconic work finished in January 1942, the eve of America joining World War II, Laing writes, “You could read the painting now as a parable about American isolationism, finding in the diner’s fragile refuge a submerged anxiety about the nation’s abrupt lurch into conflict, the imperiling of a way of life.” When considering our current state and how relatable people have found Hopper’s paintings, it can not be overstated how important the role of art as consolation can be, how art can provide a guide to hope. As people navigate the shock of their lost routines, it can be a relief to see their emotional reality reflected in art. In that context, art can function as a catalyst for processing and digesting feelings that might otherwise overwhelm.

You take the small comforts where you can get them.

The May 1963 issue of Life magazine had a profile of James Baldwin. “You think your pain and your heartbreak are unprecedented in the history of the world, but then you read,” Baldwin says. “It was books that taught me that the things that tormented me most were the very things that connected me with all the people who were alive, who had ever been alive.”

A famous quote, yes, but it continues with a line that is less-remembered: “An artist is a sort of emotional or spiritual historian. His role is to make you realize the doom and glory of knowing who you are and what you are. He has to tell, because nobody else in the world can tell, what it is like to be alive.”

And that is what Hopper’s paintings have achieved in our moment. Hopper’s “erotics of insufficient intimacy” show us the emotional register of what it is like to be alive in the time of COVID-19. So let people enjoy a sense of recognition in their encounter with Hopper’s work.