Indians and the American Story

Ned Blackhawk’s award-winning history of suffering and survival.

The Rediscovery of America

Native Peoples and the Unmaking of U.S. History

by Ned Blackhawk

Yale University Press, 616 pp., $35

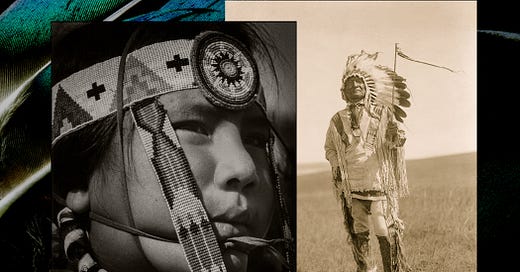

I AM SURELY NOT THE ONLY PERSON with vague memories of learning about the first Thanksgiving back in second or third grade: turkey, corn, pumpkins, and Pilgrims in funny hats alongside Indians in headdresses, sharing a celebratory feast and pledging mutual friendship. And I imagine I’m not the only person for whom those feel-good images of colonial America marked one of the last appearances of our country’s native peoples in my history curriculum. The first Americans tend not to figure prominently when we tell our national story.

Ned Blackhawk, a Yale professor of history and American studies, aims to change that with his recent book The Rediscovery of America, which last week won the 2023 National Book Award for nonfiction. “Exiled from the American origin story,” he writes, “Indigenous peoples await the telling of a history that includes them.” Beginning with Spanish settlers who pressed northward into the American southeast and Florida, following French trappers and traders who moved into the Great Lakes region from Canada, and tracking the flow of British migrating west from the eastern seaboard, Blackhawk argues that “encounter” and not “discovery” is the lens through which to understand American origins. Throughout the book, he emphasizes that relations with Native Americans are far from peripheral to the national story; instead, they helped shape the development of the United States of America in fundamental ways.

It is a sobering story, a reminder that slavery is not America’s only original sin. For five centuries, native peoples have suffered extensively at the hands of Americans: devastation in the face of European diseases, repeated incursions on traditional territories, forced removal, land cessions, broken treaties, attempts at assimilation and tribal termination. But Blackhawk does not only want to tell a tale of suffering. His is also a story of survival: of native peoples who have refused to disappear, who have adapted to repeated challenges, asserted their treaty rights, and maintained their sovereignty. Resilience, more than victimhood, is his theme.

Blackhawk’s achievement in the book is to direct our attention to the many ways in which U.S. history is closely intertwined with that of Native Americans; he shows how interactions with native peoples have shaped not only ideas of American nationhood but even constitutional structures. Of particular interest are his discussions of the revolutionary era and the early republic. In the Seven Years’ War, for instance—perhaps still better known to many of us as the French and Indian War—Britain and France clashed for control of interior lands where Iroquois and other native peoples were a force to be reckoned with. European powers sought Indian allies; Indian tribes strove to maintain their independence by playing imperial powers against each other. Britain’s defeat of the French did not mean that it now controlled the interior; to the contrary, it projected very limited force into a region populated by native peoples who had not been conquered and who engaged in both diplomacy and war to maintain their rights.

Their continued resistance proved an irritation to colonists who desired to expand into formerly French territory. Financially strapped after years of global war, Britain did not want land-hungry settlers dragging it into new Indian conflicts; efforts by the crown to respect treaty boundaries and protect natives against colonial incursions became an important grievance in the years leading up to the Revolution. (The Declaration of Independence complained that the king, among his other offenses, had “endeavoured to bring on the inhabitants of our frontiers, the merciless Indian Savages, whose known rule of warfare, is an undistinguished destruction of all ages, sexes and conditions.”)

After the Revolution, however, the new American government under the Articles of Confederation found itself facing the same problem. Unable effectively to raise either money or an army, Congress could protect neither settlers against Indians nor Indians against settlers. Blackhawk describes how volunteer militias in areas such as western Pennsylvania and Kentucky raided neighboring tribes, interrupted federal supply trains traveling to the interior on diplomatic and trading missions, and refused obedience to any government that sought to protect Indians. Insurrectionist vigilantes known as the Paxton Boys at one point even marched on Philadelphia. The young country’s inability to control such groups was among the important problems causing eastern leaders like George Washington to call for a stronger centralized government. As had been true before the Revolution, Blackhawk argues, the nation’s future was again being shaped not along the eastern seacoast, as we so often imagine, but within the interior, where settlers and squatters collided with indigenous nations. It is impossible to read his account today without thinking that contemporary resentment in ‘flyover country’ of ‘coastal elites’ has very deep roots in American history.

Washington appears as a particularly interesting figure—flawed and human, but also with a more statesmanlike perspective and broader sense of justice than many others. His military experience (which began with some rather inauspicious engagements with native forces, but also the destruction of Indian villages) and work as a surveyor—participating in the feverish land speculation that prompted so many conflicts between settlers and natives—provided him with a richer understanding of the country’s western lands than most national leaders possessed. He believed that to solidify national authority, stabilize prices, and avoid squandering the revolutionary victory, it would be necessary to respect treaties with native peoples, rein in land fever, and restore respect for government. His motives were not entirely disinterested: He was an avid buyer of real estate and stood to profit from stable land prices. But unlike many, he was prepared to deal with America’s native peoples as sovereign nations whose rights demanded respect.

Blackhawk describes similar patterns in subsequent generations. Time and again, Americans’ hunger for land and resources, along with their often fierce hatred of Indians, proved stronger than the government’s ability or desire to restrain them. This dynamic produced Indian removal under Andrew Jackson, who ignored a Supreme Court ruling in Worcester v. Georgia that affirmed limited but important tribal sovereignty. It also led many Indian nations to ally with the Confederacy during the Civil War, which gave rise to a newly strengthened national government capable, for the first time, of projecting power into the native homelands of western tribes. After the war, national policy fluctuated for another century between efforts to assimilate, dilute, or terminate the tribes and efforts to reinvigorate their authority and independence (and thus reduce the need for federal spending on their behalf). Only in the last decades of the twentieth century did momentum appear to shift in more meaningful ways toward a reaffirmation of tribal treaty rights and an effort to recognize Indians both as members of sovereign nations and also as equal American citizens. Much work remains to be done, however, as will be evident to anyone who looks up current statistics for problems like crime, sexual abuse, poverty, or suicide on Indian reservations. The harms suffered over centuries will not be so quickly undone.

READERS OF THE REDISCOVERY OF AMERICA are likely to feel conflicting emotions. On the one hand, any American patriot will inevitably feel considerable guilt at the stain on the country’s honor left by centuries of mistreatment of Native Americans. On the other hand, there is something invigorating and hopeful both in fresh efforts at cooperation and reconciliation and in enriching our understanding of American history by weaving into its tapestry the threads of the encounters that Blackhawk recounts.

Whether he would endorse the language I just used, however—of incorporating these stories into our national narrative by weaving them into its tapestry—is unclear. His title suggests something slightly different. It speaks of the rediscovery of “America,” a broader concept than the United States, and his story relies at important moments both on ignoring national borders with Canada to the north or Mexico to the south, and on imagining new ones among (settler) Americans and the many native peoples living on the continent. Similarly, his subtitle refers to the “unmaking of U.S. history.” He nowhere comments on either the title or subtitle, but that wording implies a kind of deconstruction of the United States and a shift away from the nation-state as the primary subject of historical analysis. In a couple of spots, Blackhawk associates his work with what is called “borderlands” history, which, at the risk of oversimplifying, explores movements across frontier spaces. While it frequently generates useful and provocative insights, borderlands history also suggests an alternative to—or even a replacement for—traditional national history.

My own instinct is less to oppose these two historical approaches than to read them together. A student, for example, might wish to pair Blackhawk’s volume with a more unabashedly national history like Wilfred M. McClay’s Land of Hope: An Invitation to the Great American Story. In some contexts we need to focus on the ideals of liberty, equality, and justice that the American Founders, for all their faults, boldly articulated, and that have inspired countless people all across the globe ever since. In other contexts we need a clear-eyed reckoning with the tragic ways in which we have fallen short of those ideals. By the same token, there will be some moments that call for an appreciation of American unity and shared culture, and others that warrant a focus on the rich plurality of cultures and histories that have shaped our collective experience—among them, those of the many Native American peoples who, as Blackhawk reminds us, have so often been absent from our country’s self-portrayal.

Regardless of whether Blackhawk would accept that proposal for an irenic historical eclecticism, readers will learn a great deal from his “rediscovery” of American history. In a way that is indeed profoundly American, he summons us to be touched once again, in Lincoln’s words, by the better angels of our nature. And he invites those of us whose education paid little attention to the original inhabitants of these lands to enrich our understanding of their lives and histories beyond that third-grade image of Thanksgiving.