Iran’s Celebrities Finally Break Their Silence

For the first time, Iranian athletes and artists have been criticizing the regime.

Something new is happening in Iran: For the first time, the anti-regime protests there include the participation of Iranian celebrities. The ranks of the country’s superstars are filled with actors and actresses, singers, and soccer players. Like their American counterparts, these figures are significantly more progressive than their average compatriots. Because of blackmail and blacklisting, however, they have customarily reserved their criticisms, tempered them by speaking generally about perennial issues, or even been forced to voice support for the regime.

Now, remarkably, many of big Iranian celebrities are treating the protests as their hour of decision, arriving at last. The stakes are high for them, but also for the regime: In response to this development, the country’s chief justice threatened the nation’s celebrities with the growing bill for the damages from the riots.

Soccer players, especially those on the national team, play a major role in the nation’s culture, and through participation in international competitions, Iran’s teams, under close governmental supervision, are essential to the regime’s interface with the larger world. It’s therefore significant that some of the most prominent celebrities to take an explicit stand against the government have been prominent soccer players—especially the legendary Ali Karimi.

Karimi is arguably the most talented soccer player to emerge from Iran: He capped (appeared in an international match for) the national team 127 times, captained Persepolis F.C.—the most popular club in Iran by far—and played for European powerhouse F.C. Bayern Munich. Karimi could have gone even further as a player, but the received wisdom is that his rebellious character ultimately limited his prospects: After coaching a handful of clubs, he’s recently taken a yearslong break from the sport while living in Dubai.

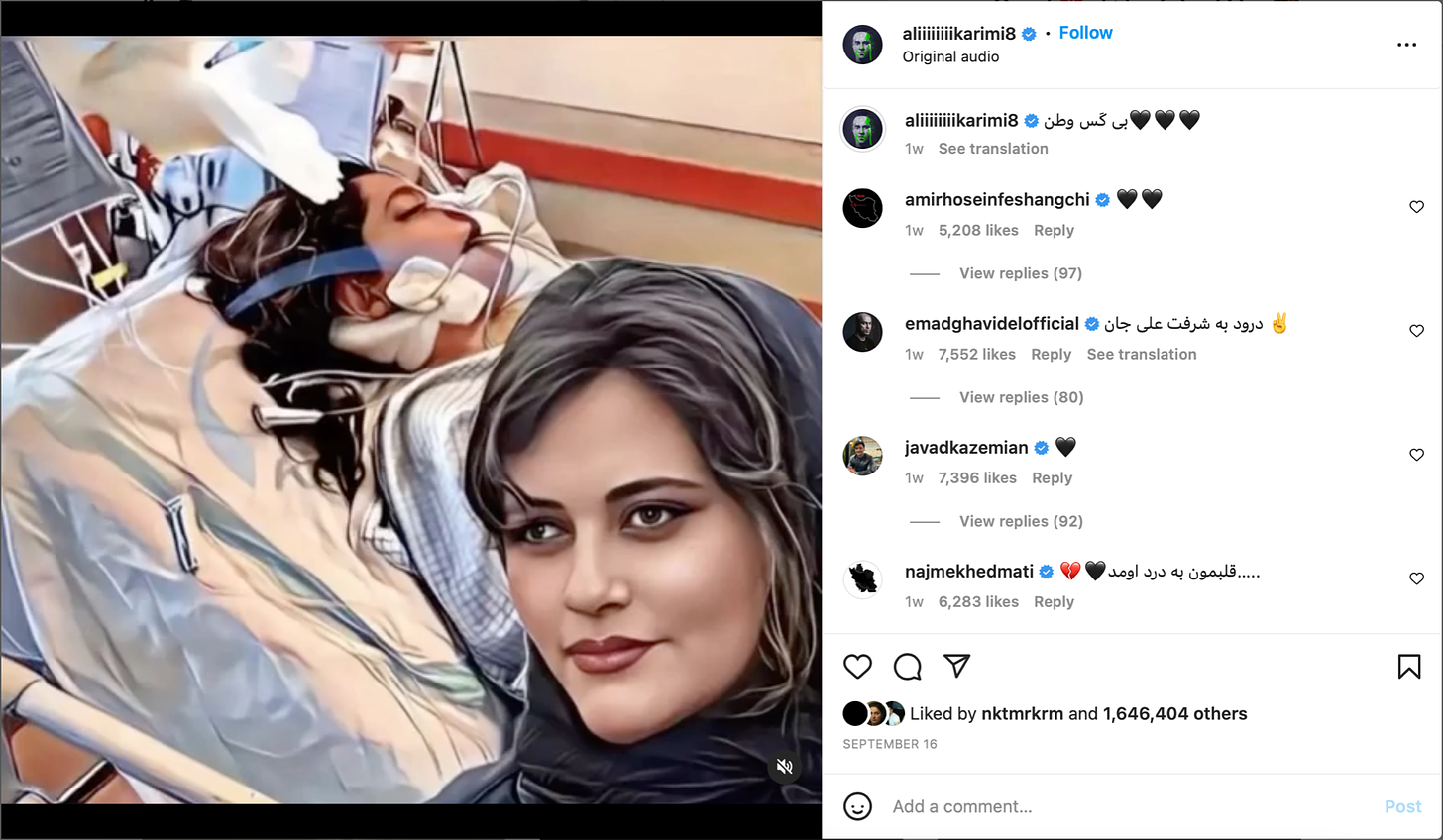

But the 43-year-old has started putting his rebellious character at the service of his nation. Over the past several years, Karimi has openly criticized the regime for the downing of Ukraine International Airlines Flight 752, rampant inflation, and other issues, which has turned him into a pariah back home. And now he’s upped his game: After Mahsa Amini’s murder—the catalyst for the current demonstrations—he posted on Instagram that Iran is an “orphan”; he has since used his social media accounts to energize the protests and keep morale among protesters high.

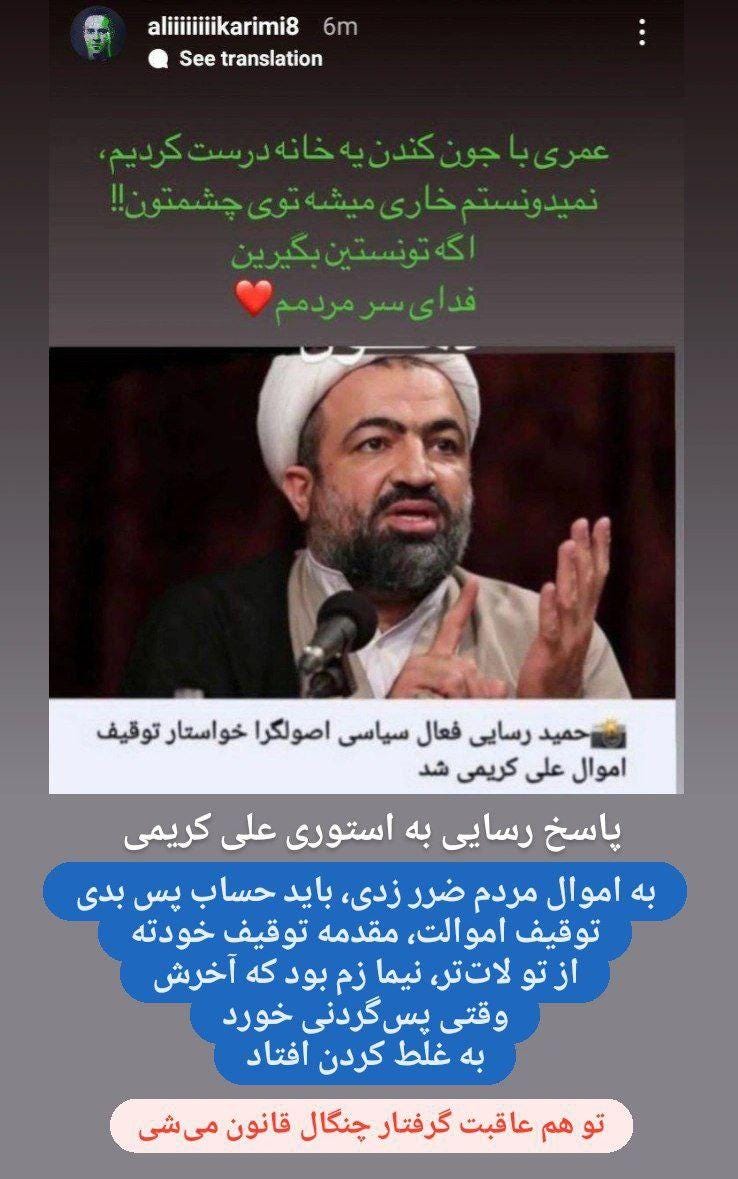

Being relatively young and far away has helped position Karimi as a moral leader in exile. The regime cannot silence him—though regime affiliates such as the Fars News Agency have made noises about asking Interpol to arrest him, a futile dream—and Karimi can legitimately claim to be making patriotic sacrifices. Back in Iran, his palatial villa has been confiscated—a loss he called “a sacrifice for the people”—and whatever assets he has left will doubtlessly be similarly expropriated. He will never be able to return to Iran so long as the Islamic Republic remains intact, meaning he’ll never be able to partake of the money the Iranian soccer industry makes so amply available to most former superstars through coaching and executive contracts.

Ali Daei is another prominent soccer player who has come out in support of the hijab protests. Until a year ago, he was the world’s all-time top scorer in international games and the captain of Team Melli, Iran’s national team. An older contemporary of Karimi, the two had their share of acrimony on and off the field. Now they are brothers in arms. Daei, also a former Bayern player, is wealthy and gives generously to charitable causes. After a devastating earthquake in 2018 and an inept government response, he made a stunningly large donation to the victims—and it earned him the wrath of the regime. He too is now voicing criticism of the system. Most recently, he posted an animation celebrating the “Free the Hair” movement, telling the protesters, “I will forever be by your side.” It is a risky message: Daei is not aligning with a reform movement but a revolutionary one whose members chant “Death to Khamenei” and call for the overthrow of the regime.

Other soccer players, retired and active, are also beginning to come out in support of the protests: Karim Bagheri; Mehdi Mahdavikia, a former Asian Football Player of the Year; and Farhad Majidi, a former captain of Iran’s second most popular team (and my favorite). Though not known for his political courage, Majidi posted a video of guards beating women, adding, “you can’t see these scenes anywhere in the world. How do you call yourselves humans while you [don’t know what it means to be one], that you beat your compatriots like this? Fear the oppressed.”

Some active players have spoken out as well, even though the risk to their careers is greater. In less than two months, Iran will compete at the World Cup in Qatar. It’s a setting in which players customarily try to make a name for themselves to get a lucrative transfer abroad. The national team is a symbol of national unity, but rumors have been circulating that since the team assembled in person for its run of pre-Cup friendly matches, it has been riven by internal conflict over how to respond to the recent unrest, with the regime pressuring the team to offer no comment even as the public pressures them to speak. Some players purportedly want to remain silent until the World Cup—perhaps in the hope of getting out—while others are running out of patience.

Sardar Azmoun, already playing in Germany and perhaps Iran’s best active player, broke his silence last week. Blaming his prior hesitation on the soccer federation’s rules, he continued:

I ran out of patience. Worst comes to worst, I’ll be kicked out [of the team], a sacrifice for one strain of hair of Iranian women. This [Instagram story] won’t be deleted whatsoever. They can do whatever they want. Shame on you who kill people so easily. Long live the Iranian women.

A day later, he scored for the national team and refused to celebrate. His Instagram profile was scrubbed of posts going back almost a decade shortly after. (The posts have since been restored.) The rest of the team has changed its profile to a black map of Iran, a symbol of protest and grief. Two days ago, starting players on the field covered the Islamic Republic’s logos on their jackets during the national anthem as a gesture of solidarity before a match with Senegal. Security forces are putting pressure on the team to delete their social media.

And Zobeir Niknafs, a midfielder for Esteghlal, posted a video of himself shaving his head in solidarity with women who can’t show their hair.

Iran’s arts community has enthralled audiences across the world, and members of that community have also rallied to the women’s cause. Homayoun Shajarian, the son of the late maestro Mohammad-Reza Shajarian and a popular musician in his own right, projected a portrait of Amini during a concert abroad in Germany. The crowd chanted “Death to [every] dictator!” in response. He won’t be performing in Iran anytime soon. Ehsan Khajeh-Amiri, another popular singer, posted on Instagram, “the knife has reached the bone [a Persian expression for absolute misery]; end this injustice; we die every day to live a moment; recall these Brainless Shabans [the late strongman infamous for beating up Shah’s critics].”

Another musician, Mohsen Chavoshi, posted a video of guards beating female bystanders apparently at random and wrote that

Today and all these years, wherever I spoke from Khuzestan to Kurdistan [both minority-majority provinces] and everywhere in this homeland it has been out of love for these people—full stop. These very people who are being beaten up cowardly and innocently.” He continued, “I, Mohsen Chavoshi, in full mental and physical health, announce that I end all my work with the Ministry of Guidance [Iran’s culture/censorship ministry], etc. for work permits and like always will sing for people's will and love. Silence is no longer permitted.

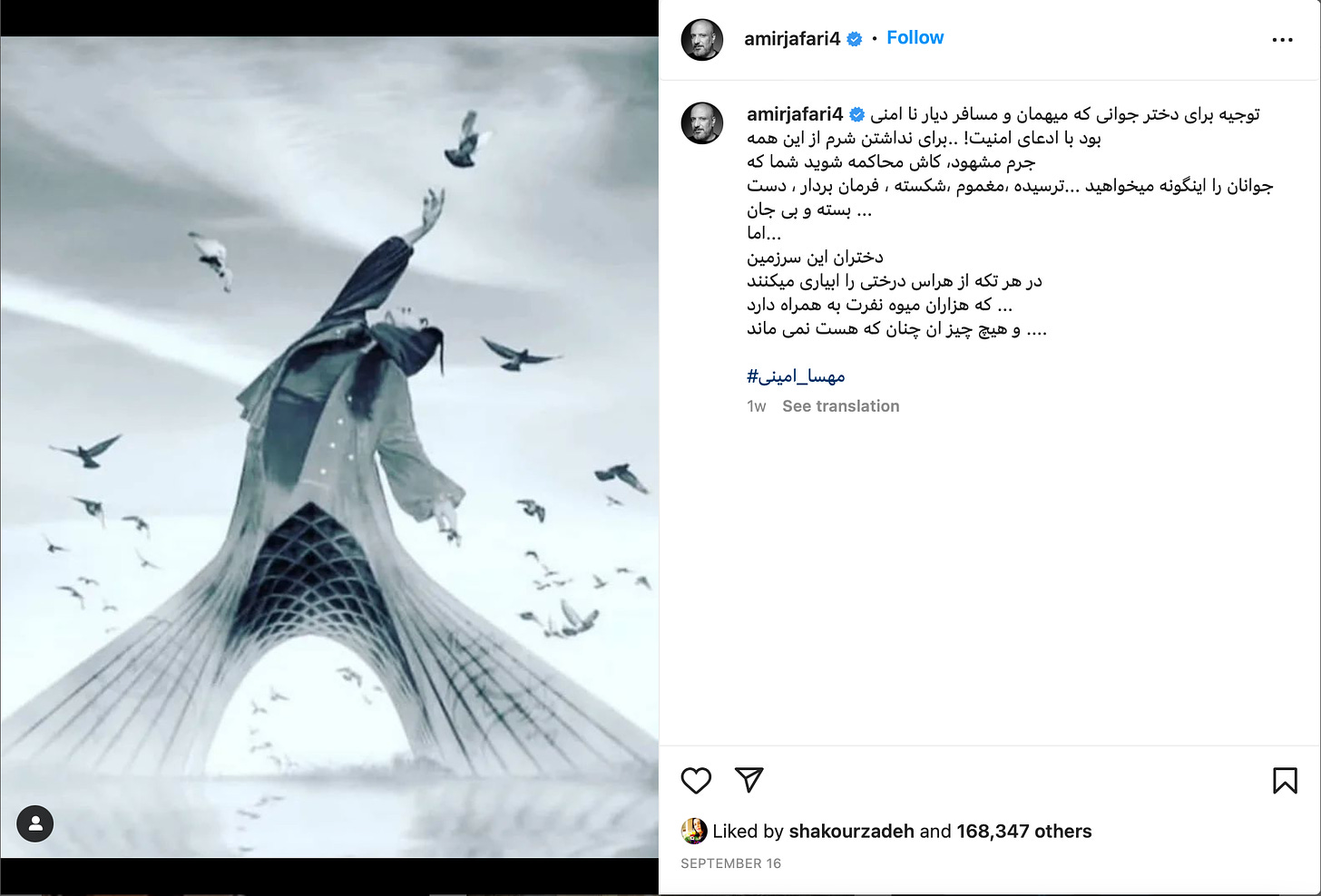

Oscar winner Asghar Farhadi has urged international solidarity with protesters. Although the regime has in the past blacklisted stars for adverse political speech and prevented them from continuing to work in the country’s entertainment industry—like soccer, one of the few remaining places in Iran where it is possible to make real money without working directly for the regime—other filmmakers and actors have shared similar sentiments. Amir Jafari, a nationally beloved comic actor, posted on Instagram an uncharacteristically dark message:

Amir Jafari: “For not having shame for all these crimes, I hope you . . . stand trials, you who want the youth like this, afraid, grieved, broken, obedient, with their hands tied, and lifeless. But the daughters of this country in every part will water a tree by fear that bears the fruit of hate, and nothing stays the way it is now.”

Reza Attaran, an actor-director, commented that “we have been dead for a long time.”

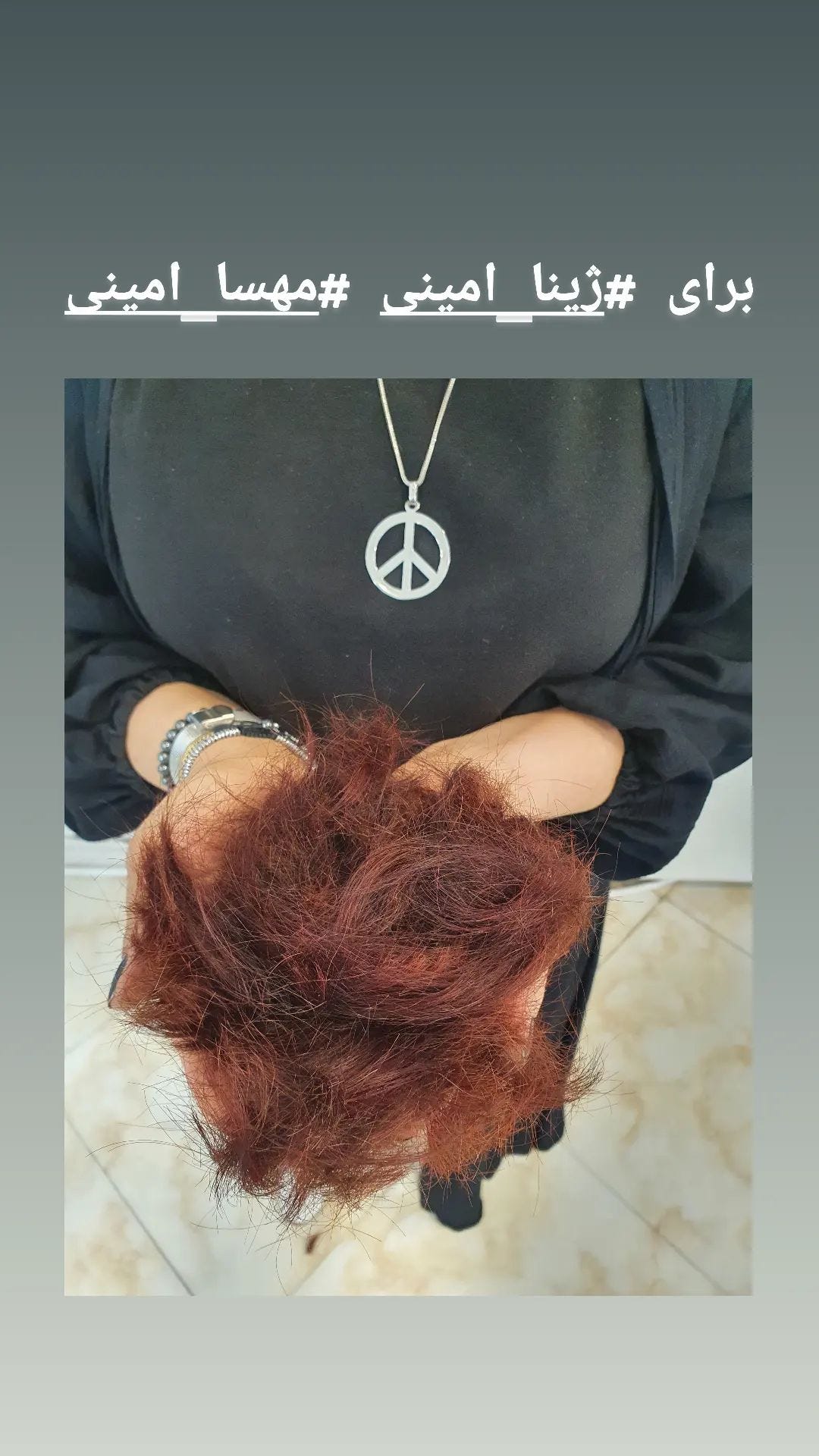

Anahita Hemmati, an actress, cut her hair in protest:

Fellow actress Maryam Boobani posted a picture of herself without hijab, her silver hair free, with a caption that began, “40 and something years of pain has whitened my hair”:

And a few days ago, high-profile figures from across the industry signed an open letter of support for the protests.

This is a major shift in the way Iranian celebrities make use of their fame; each day, the examples continue not simply to accumulate, but to multiply. Even as aligning with the protests becomes more popular, these statements, posts, and gestures of solidarity continue to surprise observers because for now, the dangers to life and career remain as they have been. Some of these figures are risking their futures. Others appear to have simply written them off for the sake of seizing the moral moment.

The actor Reza Kianian, a giant in Iranian cinema and TV, reacted to the judiciary’s threat to force celebrities to pay for damages resulting from the demonstrations. His response captures the significance of the change of heart among the country’s most famous citizens:

You have been trying for years to slur the word “celebrity,” but you can’t. We know how much you like that celebrities were on your side and regret [that we aren’t]. You’re like flowing water, and the celebrity is like the rock. The celebrity will remain [while you will pass]. You are responsible for the protests in the streets. You are not the people's representative. Quite the opposite. People are demanding their rights against you. The rights you have denied them. . . . [The] celebrity's home is in the people's hearts. That you don't have it is why you resent it and are jealous. . . . You didn't hear the silent millions in 2009. You didn't hear the protest of the poor and the youth in 2019. . . . Now [the kids] whom you raised in your own schools and you educated and raised . . . yourselves [have taken the streets]. Again pretend that you can't hear. Celebrities are from the people and among the people. And this angers you.

This is a monumental event in the history of Iranian dissent, one that shows just how fragile the regime’s public support has become. Among other things, it signals that the betting odds have changed for those who stand to lose the most wealth if they place their money on the wrong outcome.

But there are less venal motives in play, too. Even those who are insulated by fame and money from the depredations of the regime have been moved to give what they can—their status—to oppose its unjust rule. May their investment yield a good return.