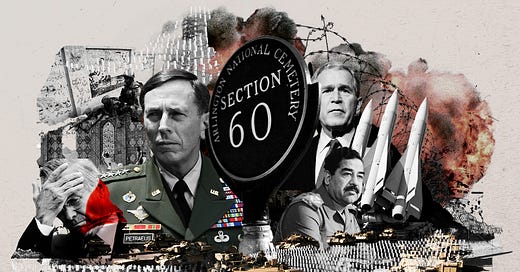

“Shock and awe.” Twenty years ago today, that was the phrase everyone kept saying as America invaded Iraq. There will be lots of analysis on this anniversary, discussions about what happened, why, and whether or not it was worth the cost.

But this is something different.

I spent nearly 1,500 days downrange in Iraq and Afghanistan, and I am still unpacking my own experience. Those memories are not pleasant, especially those from the Summer of Death in Baghdad, when destruction, futility, and defeat hung in the air. For me, there is no way to get over it until I go back through it.

June 2006

The second Iraq War produced a handful of legendary battles: the initial invasion (2003), the first and second battles of Fallujah (2004), the Siege of Sadr City (2004), the Battle of Najaf, (2004), and the overall Anbar campaign. The Summer of Death in Baghdad in 2006 wasn’t one of these historically notable campaigns. It was simply hell on earth.

This was before General David Petraeus’s vaunted surge, the Anbar Awakening, and the mythical Sons of Iraq. But it was after Al Qaeda in Iraq hit the Samarra Mosque, one of Shia Islam’s holiest sites, with multiple car bombs, triggering a Sunni-Shia civil war that would nearly break the country.

Amid this internecine fight, my unit was tasked with “training” the Iraqi Police (IP) because 2006 was dubbed the “Year of the Police” in an effort to refocus the coalition’s attention on Iraq’s neglected paramilitary force. Like in Afghanistan, the IPs would be focused on fighting insurgents, not crime. Training the Iraqi Police would come to be known as “The Air Force’s most dangerous mission.” And it would be a nightmare.

Initially, we had been slotted for our unit’s steady-state deployment providing Air Base Defense at Kirkuk Regional Airport. That changed in the spring of 2006, as the Army, stretched thin with wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, asked the Air Force for assistance in manning Police Transition Teams (PTT) for Iraq.

Initially, we were assigned to Tikrit, Salah ad Din—an overwhelmingly Sunni area in Saddam Hussein’s hometown. This wasn’t paradise, but neither was it an especially kinetic locale. However, while we were in Kuwait, finishing our last-minute quals for the job, we were reassigned to Baghdad due to that city’s deteriorating security.

After learning of our reassignment, I decided to inform my family.

My father, who would pass away during my fifth deployment, followed the war like a seasoned defense analyst. He kept detailed knowledge about the various insurgent groups, their improvised explosive device (IED) methods, and their ideological makeups. So when I called him on a hot June night on a USO phone to tell him about my new destination, an uncomfortable silence enveloped our conversation.

He knew.

There was nothing to discuss, really. My father understood that our unit would be thrust into the inferno. He was a pragmatic man of very few words, so he asked a question most fathers never ask of their sons: “Where do you want to be buried?”

So, connected by phone in the scorching night heat on the edges of the empire, we planned my funeral.

A memorial would be held in Austin, Texas. Then, I would be buried in Arlington Cemetery, Section 60, alongside my comrades-in-arms.

July 2006

What awaited us in Baghdad was carnage. Not of the fast-paced variety. It was nothing like the storming of Normandy, the Tet offensive, or the initial invasion of Iraq. It was a slow simmer, punctuated by mass atrocities. During those six months, we saw all of the insurgency’s tricks: snipers; Iranian-designed explosively formed penetrators (EFPs); complex attacks using multiple suicide bombers; and extrajudicial killings, or EJKs—which is just a euphemistic acronym for murders, a term that saps humanity out of barbaric acts and is a necessity for militaries the world over.

Although my unit responded to car bombs and other high-profile attacks, we spent most of our time tracking the dead bodies dumped casually on the side of the road. Every day, we chronicled the remains of Iraq’s civil war. We tried to identify these bodies, determine their ethnicity, and find out where they were from. Often these efforts were futile. Eventually, it became dangerous. After watching us stop and try to identify the remains, insurgents began emplacing IEDs into the carved-out stomachs of their victims, killing scores of American soldiers.

We did this every day. Rinse. Repeat.

We watched in horror as Iraqi society devolved around us. Al Qaeda in Iraq would conduct a suicide bombing in a Shia neighborhood. Shia militants who had infiltrated the police would go into predominantly Sunni communities and kill people at will. It was common to find the dead bodies of children on the side of the road. Shia militias, almost always tied to Muqtada al-Sadr’s Jaysh al-Mahdi, often raped children or other loved ones in front of parents and family members before killing them. Finding children raped, gagged, and killed in this manner is an indescribable horror. No training in the world can prepare you to deal with it.

And we saw it too often to forget.

August 2006

I’ve partnered with murderers, rapists, pedophiles, torturers, and mass killers. I learned to look past their barbaric acts out of professional obligation. Years later, in Afghanistan, I would befriend a former midlevel Taliban commander turned district governor who had American blood on his hands. At the level of the nation-state, yesterday’s enemies become tomorrow’s allies with no regard for how individuals might feel.

I say this because, in all honesty, I was forced to work with so many monsters that I’ve forgotten many (most?) of them. But the monsters we partnered with during the Summer of Death were different. Those monsters I will never be able to forget, as much as I wish I could.

The Iraqi Police officers, whom we were ostensibly training, would come back to their station from patrol with dead bodies in the back of their trucks. Often, the IPs were the ones who had murdered them. My troops routinely remarked that we were training insurgents to kill us, and that wasn’t too far from the truth. We often had to confiscate our police officers’ phones before patrols because we found that some of these “partners” were calling out our movements to the enemy. Many policemen had pictures of insurgent leader Muqtada al-Sadr in their official vehicles or wore black t-shirts underneath their uniforms with his image emblazoned on them.

They were not trying to hide their affiliation. Instead, they were proud of it. It was common for an Iraqi Police officer to show you his Sadr t-shirt and ask, “Why do you hate him?”

How do you ask young American service members to partner with people trying to kill them? How can you ask American families to send their sons and daughters into harm’s way to befriend mass murderers?

But with years of hindsight, I realize that we weren’t the best partners either. We often viewed the IPs as expendable. It was a common adage that when responding to a mass casualty event, it was prudent to let the IPs go first, so they could soak up the inevitable follow-on attacks—either from car bombs or snipers—targeting first responders.

Truthfully, we were both simply trying to survive.

In our unit, we were just trying to get back home to our friends and families. Yes, the mission mattered. However, it was apparent from our mission’s first months that some of our Iraqi partners were trying to kill us. This paradox was evident even to the most junior enlisted. And when a unit’s fundamental mission is in tension with reality, it undermines almost everything it touches. Accordingly, while we did what we could to “train” the IPs, we chiefly tried to survive and care for one another.

But the Iraqis were also just trying to survive. A young Iraqi Police officer once told me, “You have six months of this. I have this for my entire life. You go back to the base at night. My home is around the corner from the station.” Their country had been shattered. Jobs were scarce. Violence and death were everywhere. During the Summer of Death, even being neutral was picking a side, and being on the wrong side at the wrong time meant death.

That young officer was a good guy. Not every man who wore an IP uniform was, though.

The Airmen assigned to Amil District knew they were in one of the most dangerous areas of Baghdad. The insurgency lurked around every corner. Iranian-supplied EFPs—which cut through our armor like a knife through butter—littered the streets. Many troops pre-positioned tourniquets on their legs and arms before going out.

In all of this madness it seemed a small blessing when a few puppies came to play near the IP station. Our Airmen brought the puppies food and toys. It was a little decency and purity amid the barbarism.

Jaysh al-Madi insurgents masquerading as IPs observed this decency. One day in July, our Humvees pulled into their assigned spaces at the IP station. In our parking spots were our puppies. The insurgents/IPs had killed them by tossing them from the roof of the station.

Their not-so-subtle message to us, their partners: You are not welcome here.

September 2006

Every deployed area has its hotspot; the location where the pucker factor rockets up. Dora, in southern Baghdad below the Karrada Peninsula, was our hotspot. Dora was a predominantly Sunni neighborhood seething with sectarian resentment toward the IPs. It housed a significant Al Qaeda in Iraq (AQI) cell that allied with Sunni national insurgent groups and was teeming with former elements of the Hussein regime. Their alliance acted as a bulwark against a predatory government bent on sectarian revenge for the Samarra Mosque bombing (and for the last fifty years of Sunni domination).

Moving into Dora was part of Operation Together Forward II. This operation would be General George Casey’s last gasp before he was supplanted by General David Petraeus, and while it mimicked many of the tenets Petraeus made famous—clear, hold, build—it failed to squelch violence because American forces did not stay in these neighborhoods.

Instead, as always, we returned to our megabases at night.

By August, everyone knew the operation was failing. It was evident in the continued rise in disfigured bodies on the road, car bombs, and IEDs. It was failing everywhere, but most spectacularly in Dora. Nevertheless, every day we made our pilgrimage to Dora to partner with the Iraqi Police. This group would be disbanded years later for ineffectiveness and corruption, and for acting as Muqtada al-Sadr's designated hit squads.

For the last twenty years, Americans have been fed a steady diet of dramatic stories about bearded special forces soldiers, from the raid on bin Laden to the killing of Baghdadi. But the special forces didn’t do all the fighting in Iraq. Not even close. Most of it was done by regular joes who did not have ubiquitous surveillance overhead, the latest high-tech gear, or an unlimited budget. For regular joes, our time was spent the old-fashioned way: movement to contact. Translation: Go find the enemy by making yourself a target.

We were big, juicy targets, but that was the point. A procession of Americans, both dismounted and mounted in their Humvees, were joined by Iraqis both dismounted and mounted in their Ford Rangers. We stretched out nearly 50 yards long and eked our way through the empty streets of Dora.

No Iraqi dared venture outside. The markets were empty. The stores were closed. Everyone was holed up, trying to survive. Nobody wanted to talk with us. Everyone feared the repercussions. It was futile. And we all knew it.

I often found myself dismounted in the rear of our parade. Scanning. Smoking my cigarette. Scanning. Smoking. The war was boredom punctuated by acts of pulsating violence. But the monotony could kill you if you didn’t stay alert. Snipers thrived in Dora. And we were their wet dream. I only hoped the shot that felled me would be quick and painless. We all shared the same hope. We feared becoming paraplegics. Or worse, losing our genitals in an IED strike—every man’s secret fear. It was the first thing you checked after an explosion.

I first saw him duck down from the corner of my eye. I dismissed it at first, but then it happened again.

As I wheeled my body and my M4 to the target, my heart raced, and my jaw clenched. I turned to the left but saw nothing. Then again, a figure stood up and quickly dropped.

“You see something, sir?” my turret gunner queried.

“I don’t know. I can’t tell,” I angrily responded.

The turret gunner moved to mirror my stance, and the object stood up and down again.

“I saw him!” my turret gunner exclaimed.

As we waited for him to stand up again, the adrenaline rushed through my body, slowing time to a crawl. My whole body focused on one spot.

Then he reappeared 15 meters to our right on the same rooftop.

“Shit, he moved,” I said.

“Tracking.”

The figure popped back up and appeared to have something in his hand. I couldn’t tell, and neither could my turret gunner.

While the streets were barren, it was not unusual for Iraqis to hang out at dusk on their rooftops to escape the heat.

The figure stood up again and appeared to be carrying a gun.

“Was that a weapon?” I asked nervously.

“Can’t tell, sir. You have a better vantage point.”

I flipped my weapon to fire and tried to calm myself down. Breathe. Relax.

Then she came out. A middle-aged woman in black and white. She began yelling on the rooftop, her arms waving excitedly. The boy stood up and dropped his toy gun. The mother grabbed him by the arm and yanked him along. She screamed at him as they hurried inside.

Insurgents had been handing out toy guns to kids throughout Baghdad, hoping to score propaganda victories—which they inevitably did, each tragedy wrecking an Iraqi family and causing lifelong heartache for an unlucky service member.

Then the woman came out of the building, wailing. She was hysterical, speaking rapidly. I yelled for an interpreter, and one quickly scurried to our patrol’s back. He struggled to understand her because he didn’t speak Iraqi Arabic fluently, a common problem for American forces even three years after the invasion. He picked up that the woman’s husband had been kidnapped the day before, but the details were hard to decipher.

As I waited impatiently for my interpreter to do his work with pen and paper in hand, a federal policeman hurried forward to join me. The woman's face and demeanor changed immediately as soon as he arrived. Her eyes met mine, and in an instant, she scurried away.

I knew instantly that the federal police were responsible for her husband's kidnapping.

Somewhere in a Shia mosque, her husband was probably being tortured to death. Someone would find his body on the side of the road in a few days, handcuffed, blindfolded, and with a hole in his forehead from a drill bit. A technique we referred to as “the full option.”

We became intimately familiar with our partners’ barbarism. Iraqi women often came to the station to identify their loved ones, who had been killed by the Iraqi Police. They would ululate upon identifying their sons or husbands. Many would curse us for partnering with their loved one’s killers.

At night, when I’m alone and the demons come, I see that woman’s face in Dora. It haunts me. I remember her look of disgust and I am ashamed.

October 2006

Visiting Section 60 in Arlington National Cemetery is emotionally draining for me, a journey full of guilt, shame, and remorse.

During a recent trip to Washington, I made the journey to see him. I walked alone to his final resting place, on a beautiful and windy day.

Nobody else was visiting Section 60 that afternoon, so I was able to mourn alone. I saw the stones his family had recently put at his grave. They read Strength, Believe, and Friends. I took a step back and looked at his tombstone.

LeeBernard Emmanuel Chavis

AIC US Air Force

Feb 23 1985 - Oct 14 2006

Bronze Star, Purple Heart

Operation Iraqi Freedom

I knelt before Chavis’s marker, touched his gravestone, and remembered. The last time I had spoken to him, he had told me to thank my mother for the care packages she sent to the entire unit. I remembered his mischievous smile. He had gotten into a bit of trouble before we deployed. Nothing serious. Every unit encounters these problems, especially those with first-term service members.

Even so, our unit’s commander had entrusted him with our guidon. Chavis led the way into Baghdad’s cauldron.

He had dreams beyond the Air Force. Perhaps he would join the FBI or the CIA. He was set to propose to his girlfriend.

Those dreams died on the Karrada Peninsula.

The IPs had called for support for a suspected IED. Chavis’s squad responded dutifully, providing security to keep women and children back. As he raised above his turret to push them back, a sniper was waiting patiently. He killed Chavis on a beautiful October day.

On a dark, quiet tarmac, we marched onto the C-130. It was my first patriot ceremony. The first of too many.

These ceremonies are only seen by those in uniform. Not by family members, congressmen, or even the president. They belong only to us.

We all took turns saluting Chavis’s coffin, which was draped in an American flag. Some knelt before it. Others touched the flag. Most were stoic. A few wept uncontrollably. Then Chavis flew off for his final resting place.

Days later, the video came out. In a disgusting video montage, Chavis appeared third. “Juba,” the Islamic Army of Iraq’s infamous/mythical sniper, had filmed a string of recent sniper kills—and Chavis was the third. His death became insurgent propaganda.

We saw it, just once. But I still see it most days. No matter how much I wish I didn’t.

November 2006

I have lots of regrets, but it’s the choices you make that haunt you the most.

He was so happy to see us. That is what sticks in my mind. Because very few Iraqis expressed joy in our presence.

The IP commander informed us that they had arrested a man who spoke fluent English, and claimed to be an interpreter. He had been picked up at a checkpoint without an ID.

I asked to speak with him.

Upon entering the holding area, his eyes lit up and he exclaimed, “Americans!”

Relief. It was written all over his face.

He spoke a mile a minute in near-perfect English. He had been working with American forces in a nearby province. He was on vacation, visiting his family in Baghdad, when he was rolled up by the IPs. He pleaded for us to intervene. All of his badges and IDs were at home.

His story seemed plausible. You never knew what you’d find in an IP cell. Often, they arrested the “usual suspects.” Translation: Men who looked guilty. Or who were Sunnis walking in a Shia neighborhood. It was hard to tell. We didn’t have the granular level of knowledge to second-guess their arrests.

However, we could check out his story rather easily. After speaking with higher headquarters, they agreed to bring him into the Green Zone and dig into his past.

He was pleased with this decision because an American detention facility was better than the Iraqis’. Yes, Abu Ghraib was a permanent stain, but that was the exception, not the norm.

In contrast, Iraqi cells were always overcrowded. They reeked of urine and feces. The IPs often tortured prisoners to elicit confessions. The IP commander at this particular station was notorious for sodomizing his prisoners.

The English-speaking man remained in handcuffs and blindfolded (for our safety) for the trip to the Green Zone. Regardless, he thanked us profusely.

However, before we got there, someone higher up at headquarters changed their minds. This guy’s name was linked to an insurgent group. They didn’t want to bring him in, for supposed “operational security” reasons. Someone quipped that he even resembled a picture of a High-Value Individual (HVI)—which he did not.

I pushed back, arguing that we could check out his story pretty easily by calling the base he supposedly worked at.

The higher-ups didn’t budge. “The decision had been made.”

But nobody wanted to traverse the route back to the IP station, especially at night when it was nearly impossible to detect EFPs.

So we were told to just . . . drop him off somewhere.

I wish I could tell you that I pushed back harder. That I used all the levers available to me to ensure this didn’t happen. But I didn’t. I was tired. Exhausted.

So we drove a few miles. Stopped in the middle of a neighborhood. Uncuffed him. Took off his blindfold. And got him out of the vehicle.

As we drove off, he screamed for us not to leave him.

Some days, I can convince myself that he survived.

But the entire neighborhood probably saw him exit an American Humvee. It was an insurgent hotspot where collaborators were killed without mercy.

I’d like to think that he survived and that some other unit didn’t find him a few days later, his body dumped casually on the side of the road.

December 2006

Coming home is the hardest part. Harder than combat. Even harder than losing a friend.

How do you come home to your family after the Summer of Death? What do you say?

When I came home, I was utterly unprepared for reintegration. Nobody knew how to handle me. And I didn’t know how to talk to people about what I’d seen. I still don’t. Today, when I try to talk about that summer in Baghdad, my throat clinches, my jaw tightens, and the faces of the dead flash before my eyes.

It was a time before PTSD was ubiquitous. “Moral injury” was not in anyone’s vernacular. Hardly anyone spoke of reintegration. We just filled out a short form asking questions about your deployment. It was a mental health screener that everyone lied about so they wouldn’t get flagged as a potential problem.

Eventually, the Department of Defense started investing in mental health professionals. But for those who fought before PTSD became a household word, we had only each other—only our brothers-in-arms to try to make sense of a war on the precipice of disaster. We had seen the utter depravity of man. And it can’t be unseen.

Many struggled. Some were admitted for intensive inpatient treatment. There were disciplinary issues across the formation. Some separated from the military. But mostly, nobody spoke about what went wrong. Mostly, we just buried it deep inside ourselves.

For me, the nightmares began a month or so after coming home. They were—they are—always filled with the sounds of women ululating. Despite being home, I remained alert at all times. I sat with my back to the wall in every room. I drove like I did in Baghdad: Always scanning; always on alert.

Like many young service members, I sought refuge at the bar, partying with friends. Eventually, my relationship with a beautiful, kind woman buckled under the weight of Iraq’s civil war. It was the first of many failed relationships.

I buried the anger, angst, and grief deep inside. I refused to reflect on that summer in Baghdad. Instead, I chased another deployment. The rush of combat. The allure of purpose. The intoxication of finding a “good” mission.

Less than eight months after returning from Baghdad, I started training for my first Afghanistan deployment.

I had become addicted to the war. I craved the cycle. From 2006 to 2014, I deployed every other year. Deploy. Redeploy home. Train for another deployment. Deploy again.

Rinse. Repeat.

Anything so that I wouldn’t have to stay home and deal with what I had seen.

Today

In the coming years, tens of thousands of Afghan and Iraq veterans will join me as we transition to the civilian world. My brothers- and sisters-in-arms carry the weight of multiple deployments and years away from their families.

The majority of us will succeed in this transition. Our skill sets make us attractive candidates for employers. With military pensions in tow, most will live at least semi-comfortable lives.

Yet for many of us the transition will be daunting. Many service members suffer from PTSD, traumatic brain injuries, and moral injuries. Most of those who carry these invisible wounds have not received adequate treatment. The lack of sufficient mental health counselors at VA clinics and in our communities exacerbates these issues.

These wounded warriors, like their Vietnam War elders, are at increased risk of incarceration and substance abuse. Moreover, they remain targets for recruitment by far-right elements. The white power movement specifically targeted Vietnam vets with a narrative designed to prey on their feelings of betrayal, humiliation, and angst. Those same feelings exist among many of my brothers and sisters-in-arms.

Another complicating factor: While many service members deployed repeatedly, most of the civilian population remained detached from the wars. This disparity of sacrifice has caused a largely undetected amount of resentment among the active-duty and veteran population. And resentment, as many couples know, is one of the leading indicators of potential breakups.

American society must do something about this problem. The civ-mil divide must be bridged. Hearing our stories would be a welcome first step. These tales have burdened many of us for decades. By “communalizing our trauma,” we can start on the road to moral recovery.

Many veterans only give PG-13 stories when asked about their time downrange. We sanitize the truth for public consumption. After my first deployment in 2006, I met with friends over drinks. After a few too many, they asked me about my deployment and I told the truth. I told them about a dead, mutilated child we found on the road. Nobody spoke to me the rest of the night.

The lesson I took from that was that people generally don’t want to hear the truth about America’s wars. So I buried it.

But the only way to ensure a smooth transition for my comrades-in-arms is for us to be heard. Not just the stories of bravery, courage, and gallantry. But also the stories of shame, humiliation, and regret.

The discounts at stores are great. Boarding planes first is appreciated. But, after twenty years of war, many of us just want to share our stories with the people we fought for—without judgment and with your full, undivided attention.

So today, on the twentieth anniversary of the invasion of Iraq, resist the urge to dunk on your ideological opponents. Pause to reflect on the Iraqis who lost their lives. Remember our Gold Star families, whose grief is unimaginable. Pray for our service members still serving in Iraq.

Seek out an Iraq veteran and don’t just thank them for their service. Instead, ask them to share their stories.

Will Selber is a lieutenant colonel in the United States Air Force. The views expressed here are his own and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Air Force or the Department of Defense.