Is Christmas Gift Inflation Real?

A century of Christmas commercialism, as observed in old magazine ads.

HAS CHRISTMAS BECOME MORE COMMERCIALIZED than ever before? It can be tempting to think so when getting buffeted with ads for gifts months before you’d actually give them. But let’s push past the recency bias—after all, it was way back in 1965 that Charlie Brown lamented the commercialization of Christmas.1

To gain some perspective on the shifting ways in which Americans have approached the material aspect of the holiday over the decades, I plumbed Google’s repository of old Life magazines to see what Christmas advertising and gifts looked like almost a century ago.

Using this digital archive, you can track the first issue in which Christmas or holiday advertising appeared. You can get a sense of what was considered “gift-worthy.” It’s interesting to note that many inexpensive, ordinary products appeared in print as gift ideas—at least, that’s how those ads would read today. One possible side effect of being richer is that affluence puts an inflationary pressure on gift-giving: Gifts have to be “more” than the regular run of things you might pick up without any occasion, which means the things we’re buying each other are becoming ever more expensive as the regular standard of living rises.

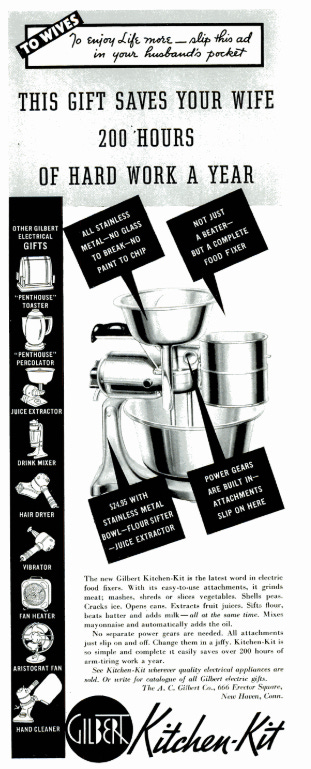

I browsed issues ranging from the archive’s earliest year, 1936, to 1966, a period that includes the release years of many of what we now consider classic Christmas tunes—the canonization, as it were, of our modern secular Christmas, and a marker of the postwar boom. It quickly became apparent that despite the well-documented phenomenon of “Christmas creep” that pushes Christmas advertising earlier and earlier each year, in that very first archived Life issue in 1936—published November 23, three days before that year’s Thanksgiving—there’s already an ad for a gift that “saves your wife 200 hours of hard work a year,” as the copy for the Gilbert Kitchen-Kit electric mixer claims.

The idea that Thanksgiving marks the proper beginning of Christmastime, then, has not strictly been true for nearly a century—if it ever was. Things like this are always shifting. The lyrics of “We Need a Little Christmas,” written for the 1966 Broadway show Mame, were apparently slightly altered over the years to account for perceived shifts in the timeline of the Christmas season:

In the stage production, the song is set after Mame has lost her fortune in the stock market crash of 1929 and she sings it to bring a little cheer to her nephew and household servants. In response they say, “But, Auntie Mame, it’s one week past Thanksgiving Day now!” The modern advent of Christmas creep has caused some to change those lyrics now to say “But, Auntie Mame, it’s one week from Thanksgiving Day now!”

People have been concerned with the holiday’s over-commercialization for decades. In 1956, science-fiction author Frederik Pohl wrote “Happy Birthday, Dear Jesus,” a speculative short story poking fun at Christmas consumerism. (It can be read online in this short story collection courtesy of the Internet Archive.) In Pohl’s tale, September is the month for “last-minute” Christmas shopping, and “O Come, All Ye Faithful” has been sped up and secularized as “Christmas Tree Mambo.”

And yet, as early as 1936—despite, or perhaps because of, the ongoing Great Depression—Christmastime already began before Thanksgiving.

Apropos of nothing—but fun to observe while we’re doing this—in between the ad for the kitchen mixer is an ad for a journey on a grand Southern Pacific passenger train and a Thanksgiving dinner–themed ad for Camel smokes (“By all means, enjoy a second helping. But before you do—smoke another Camel. Camels ease tension. Speed up the flow of digestive fluids. Increase alkalinity.”).

On December 7, 1936, an ad for Tablecraft cloths and napkins urged women to give them as gifts, of course, but it also recommended that they “make themselves a present of these fine cloths that look expensive but really are surprisingly economical.” And there’s an ad for Ingersoll watches, starting at $1.25—less than $30 in today’s money. Are watches that inexpensive still advertised in print publications these days?

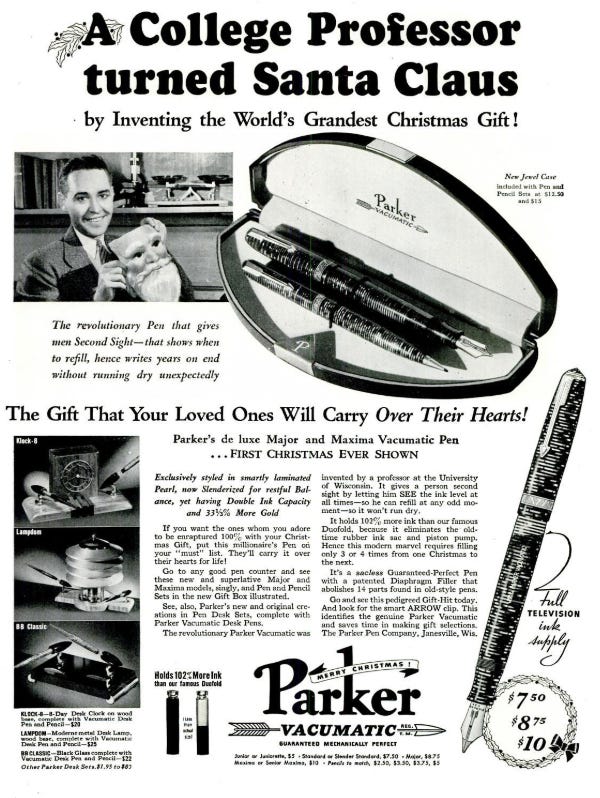

How about 1937? The November 8 issue features a Santa-adorned “Telechron for Christmas-time” ad, stating “It’s never too early, nor too late . . . plan now to give attractive Telechron clocks at Christmas-time.” Then there’s an ad for a fountain pen with a “full television ink supply” (?), which carries the headline, “A College Professor Turned Santa Claus by Inventing the World’s Grandest Christmas Gift!” One of those pens could have been yours for between $7.50 and $10—in 1937 dollars, mind you, so not nothing by any means. (Later in the issue, we learn that Czechoslovakia is a “Republic surrounded by dictators.” You know what came next.) A clothing company headquartered in the Empire State Building offers “Early Tips on Xmas Gifts.”

Going back a week, the November 1 issue has no true Christmas shopping ads, but it does have a travel ad for Jamaica—“Enjoy British colonial life in a tropical environment”—with the tagline “Come for our season of ‘Christmas flowers.’”

Let’s jump ahead to the postwar boom years. How about a full-color issue from 1956? Is there Christmas to be had on November 5? Flip past the Chrysler ad for the “Newest new cars in 20 years”—a sobering reminder of what happened to the American auto industry over the last 20 years—and there it is: “Truly . . . the gift of a lifetime” and “MERRY CHRISTMAS from mom and dad.” Every kid should be so lucky to get a Compton’s Pictured Encyclopedia! Then there’s a Four Roses whisky ad, also keyed to gift-giving and Christmas. (The liquor ads are predominantly for whiskeys and brandies—staid, respectable classics that suit the season.)

What about going still another week earlier to October 29? A couple days before Halloween wasn’t too early for Christmas either: “You give so much more when you give the year’s most advanced decanter and famous bonded Old Forester,” reads an ad illustrated with an image of miniature whisky bottles hanging on a Christmas tree bough.

Were liquor decanters a commercial field with innovations that could be tracked by individual years? Maybe Frederik Pohl was on to something.

Now let’s jump to the waning years of the postwar boom, the holiday season of 1966. October 21: Is the Polaroid ad that reads “It’s like opening a present” a hint at Christmas gift-giving? No such inferences are necessary to establish that year’s holiday window, because a few pages later, there’s an ad for a four-record compendium of newly recorded secular and sacred Christmas songs, Christmas at the Fireside. That issue also includes a feature on churches incorporating jazz and rock music into their worship, and an ad for a plain old Toastmaster-brand electric heater promising “instant heat.”

AFTER SPENDING TIME IN THE LIFE ARCHIVE, I’ve come to feel there’s something a bit strange about the consumerism of this period—but maybe it just looks that way from so many years in the future. The plainness and simplicity of many of the gifts—pens, clothes, countertop appliances, televisions and radios, electric shavers, fine whiskeys—seem at odds with the compositional intensity of the advertising. Quaintness and radicalism here go hand in hand.

But maybe “quaintness” is just a filter we lay over the past. What may have seemed extravagant in one era can seem pleasantly plain and old-fashioned in another. The color stereo TVs and the solid-state electronics were real innovations in their time. The past did not seem old-fashioned to those who lived it. One day, a smartphone may seem similarly quaint, a curious little reminder of the simplicity of life in earlier days.

Is Christmas more or less commercialized today? It’s hard to say. On the one hand, the big-box stores sometimes begin stocking Christmas merchandise as early as late August. On the other hand, explicitly Christmas-themed print-magazine ads in October, before Halloween, do feel like a bit much, even today.

Narratives always involve simplification, and it’s also possible to overinterpret bits and pieces of popular culture. But paging through these digitized old issues of Life is a fascinating exercise, and a window into a country that was very nearly, but not quite, our own. Merry Christmas!

Amazing to worry about the commercialization of Christmas in a cartoon originally sponsored by Coca-Cola.