One reason for Netflix’s massive success in the streaming wars—arguably the biggest reason it generates some $31 to $32 billion a year, give or take a hundred million bucks here and there—is its first-mover advantage. Basically: Netflix was the first standalone streaming company most people signed up for, either because they already had Netflix’s DVD-by-mail service and the online component was just a bonus or because it was pretty cheap and convenient to sign up for streaming.

Netflix generated huge subscriber numbers at least in part because it threw tons of money at studios for their libraries at a time when DVD revenue was collapsing and executives needed to hit revenue marks to ensure they got their bonuses. I believe I’ve highlighted this before, but it’s one of the key little nuggets of information in Dade Hayes and Dawn Chmielewski’s Binge Times so I’ll highlight it again:

“[Netflix CEO Reed] Hastings and company deftly exploited the studios’ compensation structure, which paid rich bonuses when executives hit their financial targets. Netflix flashed enough cash to exploit this short-term focus on profits. Some studio executives would brag about picking the novice’s pockets. The true toll of these deals would only be apparent years later, as Netflix achieved a seemingly insurmountable lead over the hidebound entertainment establishment.”

It's a real capitalists-will-sell-us-the-rope sort of moment, and one that every studio exec has kept in the back of their minds these last few years. (At least until David Zaslav realized he could send portions of the HBO library to Netflix for cash that would help him lower Warner Bros.-Discovery’s debt load, which in turn would net him huge paydays, which is definitely not a sign that history is repeating itself in its farce phase.)

Anyway, I’m getting sidetracked: Netflix used this enormous film and television library to entice audiences and, as a result, Netflix became part of the average home’s entertainment complex. Whether a supplement to cable or the cornerstone of the cord-cutters' rebuilt TV package, familiarity with Netflix grew until it became an invisible line item on a credit card every month, right up there with car insurance or grocery bills. And for a while—when the competition was light and the price was right—audiences loved it.

But they may be falling out of love, judging by the trendlines from Whip Media’s survey of customer satisfaction, which you can access here. First look at the downward slide of the three biggest players in the field, Netflix, Disney+, and Max/HBO Max:

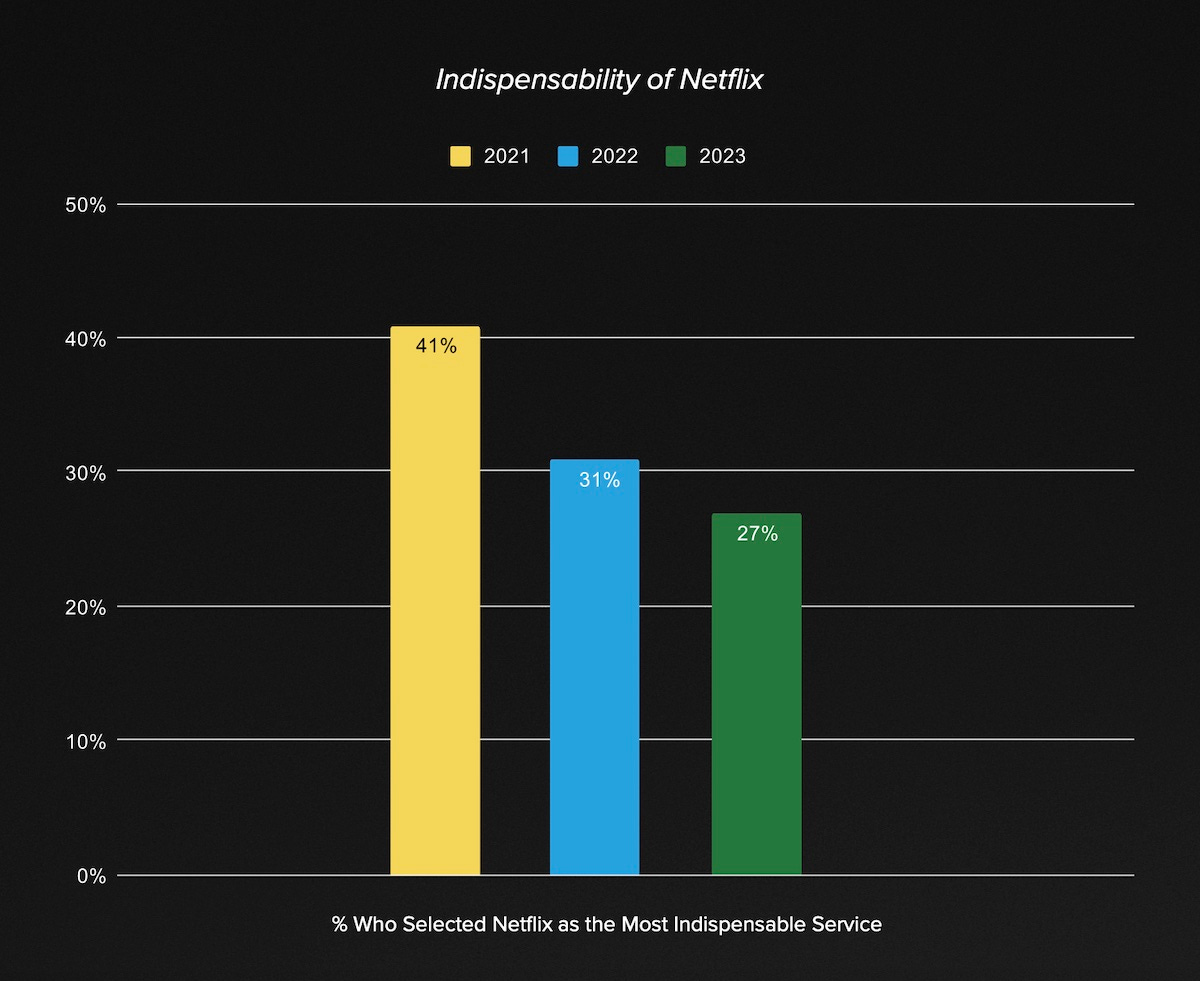

The volatility of Max/HBO Max is interesting but to be expected, given that the average consumer has been jerked around from one platform to another with little to no heads up about what’s happening. But that trendline for Netflix is pretty shocking: a 13 percentage point decline between 2021 and 2023. This next chart may be even more troubling:

This chart reflects the percent of respondents who answered “Netflix” when asked “If you could only have one streaming service, which would it be?” A 14 percentage point dip from 2021 to 2023 reflecting a loss of nearly one-third of their most loyal supporters is … probably not ideal.

Now look: none of this seems to have resulted in actual cancellations. Yet. Netflix hit 247 million subscribers worldwide at the end of the last quarter, at least in part thanks to a crackdown in password sharing prompting new signups. But first-mover advantage only really holds so long as people don’t start questioning the value of their subscription. And with more price hikes, a greater effort to shift customers to ad-supported tiers, a notable slowing in the creation of viral phenomena like Stranger Things and Tiger King, and the rise of cheaper services like Peacock and AppleTV+ alongside the so-called FAST (free ad-supported streamers) channels, Netflix is, for the first time in its history as the streaming leader, facing real questions of whether or not it is worth what it costs to subscribe.

Subscribing to Bulwark+ is almost certainly worth your hard-earned dollars, given the enormous amount of stuff to which it grants you access: bonus episodes of Across the Movie Aisle (this Friday’s breakdown of SAG-AFTRA’s AI-oriented concerns is a doozy); daily newsletters by JVL and Charlie; ad-free versions of Charlie’s pod, The Next Level, and Beg to Differ; Joe Perticone’s must-read Capitol Hill dispatches; and so much more. All for just $8.33 a month if you sign up at the annual rate.

Links!

Tip of the hat to the Entertainment Strategy Guy, which is where I first saw the Whip Media survey. Read him! He’s smart, smarter than me, even.

This week I reviewed Dream Scenario, the movie where Nic Cage starts showing up in people’s dreams. As a metaphor for viral fame and the Kafkaesque nature of cancel culture, I think it mostly (though not quite entirely) succeeds, but as a character study of a guy who thinks he deserves more than he has even when he has everything anyone should want, it’s pretty great. Cage is doing wonderful and weird work here. Check it out if it’s playing near you now; it goes wide Thanksgiving week.

One of the fun things about my podcast, The Bulwark Goes to Hollywood, is that I’m never entirely sure where it’s going to go. So I was excited to get Terri Davies on to talk about efforts by the Motion Picture Association to stop piracy before a movie is even released, which led to a discussion about Sony’s efforts to manage the analog-to-digital transformation of the 2000s, how the 2011 tsunami crippled the manufacturing of physical tapes used to transmit media, and how business continuity planning plays a key role in keeping piracy under control.

There’s some lingering controversy about the artistic choices made in Killers of the Flower Moon, specifically the decision to “center” the story of Ernest Burkhart (Leonardo DiCaprio) rather than that of the Osage people he and his uncle killed over the years. I guess I can’t help but look at this and kind of shrug because if you’re making a $200 million movie based on David Grann’s book of the same name and you’re paying DiCaprio $40 million to star in it the center of the film is either going to be on Burkhart or the FBI agent who caught Burkhart, as those are the two roles DiCaprio can play.

Anyway, as I noted in my review, I think Scorsese made the right call for the story he was really trying to tell: one of a community blinded by greed that was easily corrupted by a charismatic leader into committing a series of stupidly obvious crimes they knew would go unpunished.

Alyssa’s piece about the AI toys at the Toy Fair is up! Read it, it’s fascinating.

RIP Roger Kastel, who painted the iconic posters for Jaws and The Empire Strikes Back.

I am pretty excited for the forthcoming 4K releases of The Abyss and True Lies.

Assigned Viewing: Sick of Myself (Showtime)

Rare assignment from me in that I haven’t actually seen this movie yet. So I can’t promise it’s great. I wanted to watch it last year but never found the time. But it’s by the same guy who directed Dream Scenario and my understanding is that it deals with similar territory about modern notions of fame, virality, etc. Should be interesting!

Two somewhat interrelated developments also contributed to what you are reporting

1. Netflix-as-Must-Have:

No one expected Netflix's streaming business to take off as quickly as it did, including Netflix. In retrospect it makes sense-- slow download speeds were preferable to frequently scratched and unwatchable DVDs, especially when that scratch announced itself an hour into a movie.

Stufios realized that streaming Netflix was going to cut deeply into DVD sales and so they put the screws on Starz, who supplied Netflix with most of its first-run movies for streaming and soon Netflix had no more first-run movies to stream.

Fortunately, Netflix had the bright idea to hit up the networks and studios for TV series that had not yet reached the 100-episode mark where they'd be eligible for syndication, but were already in Sesaon 3 or Season 4. That meant all those episodes were sitting on the shelf collecting and unmonetizable. Netflix offered them big bucks for the shows, which was sort of found money for the studios, and suddenly the conduit opened up and everyone was sellling their library TV shows to Netflix. *That* was when they became indispensible and a part of everyone's must-have list--when they had a major collection of TV series. The "proof" of how well this worked was AMC and "Breaking Bad" and "Walking Dead" - it is generally achknowledged that sellling older seasons of those shows to Netflix helped them find an audience, who then returned to AMC to watch new episodes. That was what really got everyone to sell to Netflix back in the day--the desire to be the next "Walking Dead."

2. Netflix's Troubles

You remember that scene from "South Park" where the Netflix executive is greenlighting every show anyone calls in? Once the networks and studios started launching their own SVOD services, they also started pulling back all their library content from Netflix. So Netflix went on a producing spree and also changed programming chiels to try and go more mass market. This hurt their reputation. People were used to Netflix standing for HBO-like shows like "Orange Is The New Black" and "Stranger Things", not remakes of "Full House" or the Marie Kondo show. (And those were actually two of the better ones.) So the buzz started to form that Netflix's quality had really gone down. At the same time, the other SVOD services (HBO in particular) managed to log some of those HBO-like hits. So suddenly Netflix looked a lot less necessary and a lot more like everyone else, and given they were one of the more expensive services, that did not help their cause either.

(Also, glad you called out Dawn and Dade's book. Granted they are friends so I am likely biased, but I thought the book was excellent and very well written, a really well-done snapshot of the era.)

Because Netflix had a fairly wide open field and had a big checkbook, it could take chances. In its endless appetite for more content, it look to foreign films and shows, many of which were much better than the average here, often the top shows from the countries producing them.

But, the insatiable demands for growth, let alone maintaining their market leadership, had the effect it always has -- diluting strength with spinoffs, copy-cats and one retread too many. We saw this with HBO; does anyone think that it would greenlight a quirky show like “John from Cincinnati” today?

Now, all of the streaming services are trying to compete from a defensive crouch, their lineups less and less differentiated. The whole streaming market is regressing to the audience taste mean, instead of something for everyone, its more like one thing for everyone. As production costs (not to mention debt service) mount and competition increases, the streaming services will continue to flounder through rounds of failure, divestment, consolidation and reinvention trying to recapture that magic of the early HBO and Netflix.

Netflix’s first mover advantage was always at risk, because there were no insurmountable barriers to entry; deep pocketed players, such as Apple and Amazon could throw vast amounts of money at establishing a market position, while other players, including the major networks, independent content, creators, such as Disney and Paramount, as well as delivery systems, such as major cellular and cable networks, have become too nervous to not jump in the game as well. As far as I can, tell, an extraordinary amount of money, attention and analysis is being applied to figuring out how to succeed in the long term, but no one has any idea what the long term is going to look like. my guess is that if Netflix wants to retain its first mover advantage, it should continue to pursue high quality content, whether in English or other languages, and avoid the trap of trying to look like everyone else. In five years or so, when the dust has settled Netflix good night only retain its position, but have exceptional assets, including a large library, a more distinct market identity and the reputation of backing content creators.