JD Vance Wants a Constitutional Crisis

But what he *needs* is to bone up on the separation of powers.

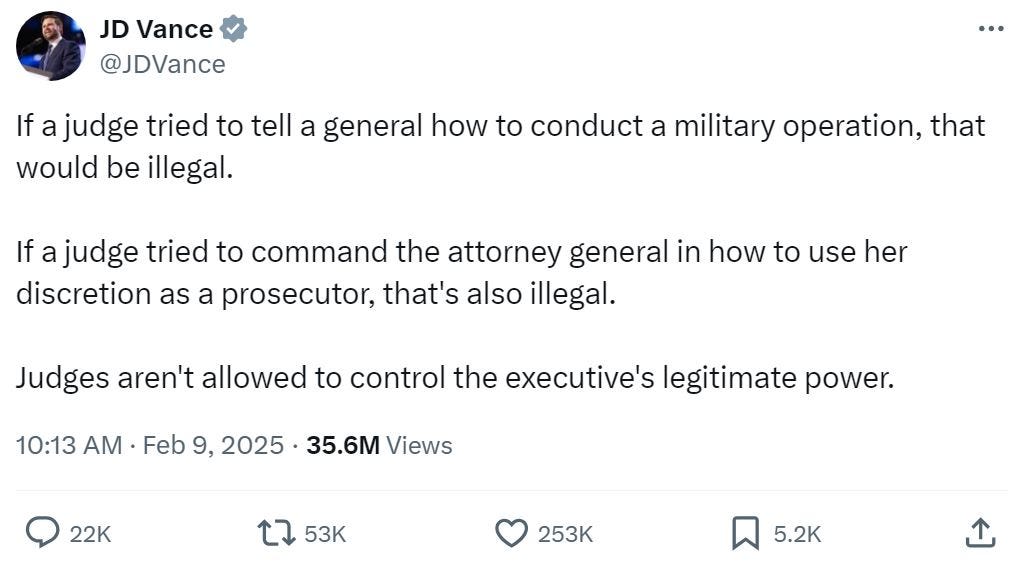

ON SUNDAY MORNING, Vice President JD Vance, a graduate of Yale Law School, posted the following on X:

Oy. Where even to begin with this?

Let’s start with the reason for Vance’s tweet. President Donald J. Trump had a rough week in the courts. As of Saturday, he had already been slapped with eight injunctions halting actions that he had taken since his second inauguration, including: his unconstitutional attempt to undo the Constitution’s guarantee of birthright citizenship; his attempt to freeze upwards of $3 trillion in government spending appropriated by Congress under its Article I authority; the “Fork in the Road” email sent to millions of federal employees, with its supposed offer of “deferred resignation”; his firing of inspectors general and other officers who are supposed to be legislatively protected from termination without cause; his coldhearted transfer of transgender women to men’s prison facilities in contravention of the Eighth Amendment’s protection against cruel and unusual punishment; and the threat of his making public the names of FBI agents associated with his retaliatory purge of those who participated in investigations of the crimes committed on January 6th. (And that’s not even counting the actions taken by courts to rein in Elon Musk and his DOGE crew.)

Vance is undoubtedly setting the stage for the inevitable: Trump’s flouting of federal court orders, which, given Congress’s obsequious fecklessness, is the last bulwark against Trump’s assaults on the rule of law and constitutional order.

FOR NON-LAWYERS, or for anyone else who hasn’t thought about high school civics for a while, the notion that courts shouldn’t butt into the president’s business might seem to make sense. Federal judges aren’t elected; they are appointed for life. The president, though, is the nation’s top law enforcement official, and appoints the attorney general, who decides which cases to prosecute and which to decline. Judges get to hear those cases when they make their way to court, but have no business telling prosecutors which people to prosecute and which should get a pass. To allow courts to interfere in such business, Vance cynically suggests, is intolerable and unconstitutional judicial overreach.

But given the context of what happened this week, Vance’s post is grossly misleading—if not patently false—and he knows it. He knows it because he learned about the proper role of the federal courts at Yale Law School in his first-year constitutional law class. (And if he didn’t learn it, he should ask Yale for a refund and maybe should mail back his diploma.)

As someone who teaches con-law to first-year law students, I can tell you that Vance, like every American law student, undoubtedly studied a landmark case called Marbury v. Madison.

In November 1800, Republican Thomas Jefferson was elected to succeed Federalist John Adams as president. Late in John Adams’s lame-duck stretch, as Jefferson’s inauguration drew near, the Federalist Congress passed the Judiciary Act of 1801. It sought to entrench Federalist control of the federal judiciary by creating sixteen circuit court judgeships and forty-two justice-of-the-peace positions. The idea was to facilitate last-minute court-packing by the Adams administration.

In the waning hours of his administration, Adams put forth names for these newly created positions and the Federalist-controlled Senate rapidly confirmed them. Among them was William Marbury, named a justice of the peace for the District of Columbia. Adams signed Marbury’s commission, and his outgoing secretary of state signed and sealed it.1

But a person ordered to deliver several commissions, including Marbury’s, before Jefferson’s inauguration failed to do so.2 Once in office, President Jefferson declined to recognize Marbury’s or any other undelivered commission. (In 1802, Congress, now dominated by Republicans, repealed the Judiciary Act of 1801, eliminating the new offices it had created.)

Marbury sought what’s called a “writ of mandamus” from the Supreme Court compelling Jefferson’s new secretary of state, James Madison, to deliver the commission. An earlier statute, the Judiciary Act of 1789, gave the federal courts the power to issue writs of mandamus.

Writing for the Court, Marshall held that the statute giving the court the power to issue mandamus was unconstitutional because the Constitution’s text did not contemplate that kind of power for federal judges. So the Court declined to issue the writ. Marshall presumably calculated that Madison would defy such an order anyway, thereby undermining the Court’s legitimacy. But in the same opinion, Marshall wrote that Marbury did have a vested right to his commission, meaning Jefferson should have recognized it. He also made clear that the question of whether Marbury had that right was a legal question, not a political one, and that it is up to the federal courts to decide whether the other branches act legally.

Vance’s tweet strikes at the very heart of the ruling in Marbury. It signals Trump’s likely intent to take the very action that Marshall feared: thumbing his nose at a court order. But the federal judges who have, so far, ruled against Trump did so after comparing his conduct against laws enacted by Congress and deciding that he has violated them. This is basic separation-of-powers stuff, and it’s a far cry from a judge directing Attorney General Pam Bondi to prosecute someone or ordering Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth to take troops in battle.

In short, Vance’s tweet is obfuscation and distraction, and a dark warning. And it’s not a one-off; remember that Vance has been suggesting since at least 2021 that a re-elected Donald Trump should defy the courts. It’s unconscionable for any lawyer to do this, let alone a lawyer who is the vice president of the United States.

A BRIEF FINAL NOTE: Article II the Constitution says that the president “shall take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed.”

And on January 20, Donald Trump for the second time took an oath to “faithfully execute” the office of president and to “preserve, protect and defend the Constitution.”

Faithfully executing means complying with the law. When a president fails to follow the law, he is failing in that responsibility. And if a president were to then disobey the courts that point out that failure, he would be failing to preserve, protect, and defend the Constitution.

Bizarrely, Adams’s secretary of state just happened to be John Marshall, who had recently been appointed to the Supreme Court as chief justice. He was simultaneously serving in both roles. And would end up writing the Supreme Court decision that emerged from the incident.

Also bizarre: The person who failed to deliver these commissions was John Marshall’s brother, James, who had himself just been made one of Adams’s last-minute judges.