1. Group Therapy

Last week Sarah invited me onto The Focus Group. The episode is out. You can subscribe on Apple Podcasts here or listen to it here.

We watched a group of nine Democratic voters in Pennsylvania who ran the gamut—from Bernie-stans to a lady who had voted for Trump in 2016.

Every single one of them thought Biden was doing a bad job.

But that’s not the bad news.

Every single one of them thought things were crappy in America right now.

Still not the bad news.

Not one of them liked Biden personally. They all viewed him as a normal, lying politician.

Now we’re there. Here’s the really bad news:

None of them believed that Republicans were to blame for the administration’s failures.

If you are a Democrat, this should scare the living death out of you. Because it means that your own voters:

Think the environment is bad.

Blame you for it being bad.

Don’t like you in the first place.

Aren’t even seeing you as the lesser evil.

No happy talk. No wish-casting. No both-sides-ing.

2. Wrong Track

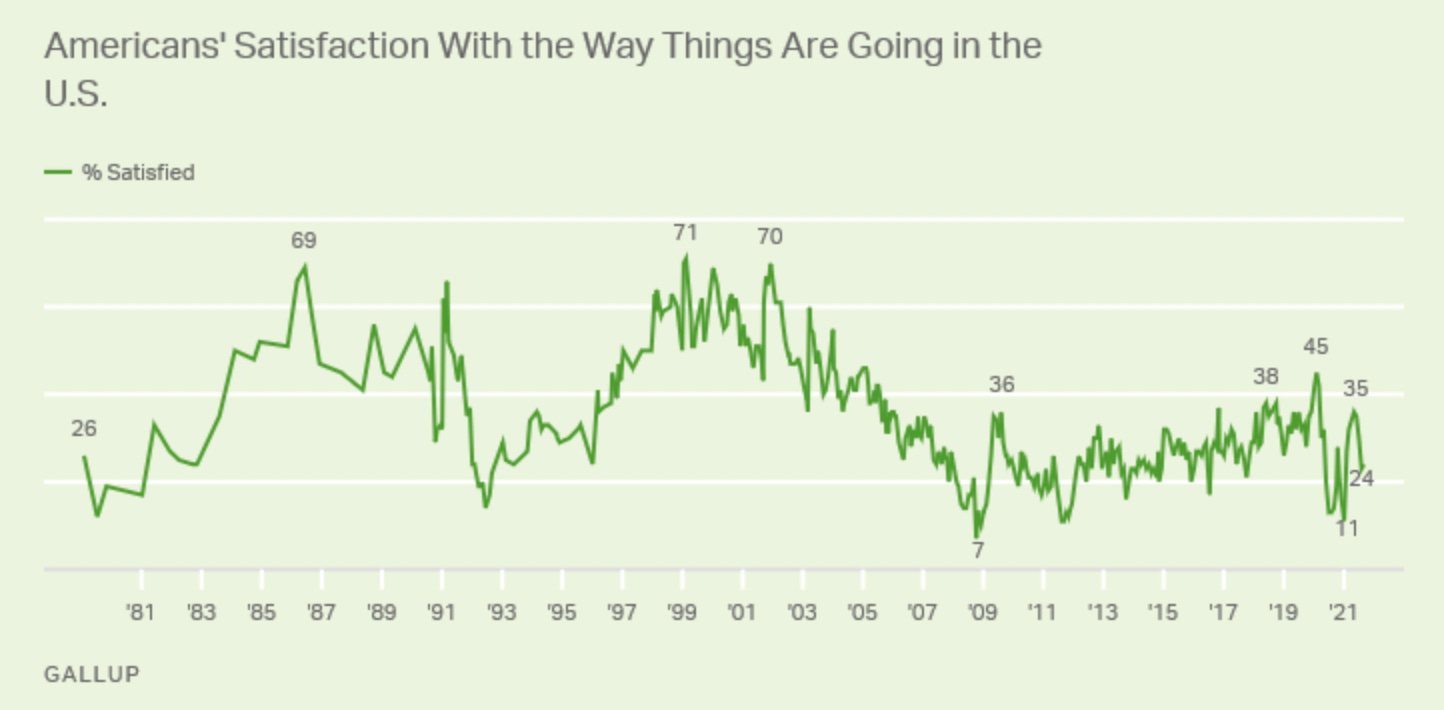

You know the venerable right track / wrong track question Gallup has been asking since the dawn of time?

Here is a question for you: When is the last time that > 50 percent of the country said America was on the right track? Go ahead and think on this for a minute.

You ready for the answer?

And even that month was an aberration. Gallup asks this question every month and since July of 2002, we’ve been over the 50 percent mark on right track exactly six times.

This graph is telling a story. But which story?

We are in the middle of a generation-long national malaise.

Political polarization has made it so that at least half the country believes we are on the wrong track simply because of which party is in power.

We have been genuinely on the wrong track for a generation due to systemic failures (income inequality, declining middle-class, institutional collapse, etc.).

The real answer is probably a combination of all three stories, mixed with some other factors.

And we’ll interrogate this question later in the week.

But as a matter of practical politics, it means that candidates need to organize their campaigns—and their governance—around the understanding that voters are (and will continue to be) dissatisfied with the world around them.

Trying to convince voters that things are actually on the right track is a mug’s game.

Now tell me: Which of our political parties is built around an understanding of this basic fact of modern politics?

3. This Is a Real Thing That Happened in America

Read this investigation from ProPublica. All of it. No matter how sick it makes you.

Three police officers were crowded into the assistant principal’s office at Hobgood Elementary School, and Tammy Garrett, the school’s principal, had no idea what to do. One officer, wearing a tactical vest, was telling her: Go get the kids. A second officer was telling her: Don’t go get the kids. The third officer wasn’t saying anything.

Garrett knew the police had been sent to arrest some children, although exactly which children, it would turn out, was unclear to everyone, even to these officers. The names police had given the principal included four girls, now sitting in classrooms throughout the school. All four girls were Black. There was a sixth grader, two fourth graders and a third grader. The youngest was 8. On this sunny Friday afternoon in spring, she wore her hair in pigtails.

A few weeks before, a video had appeared on YouTube. It showed two small boys, 5 and 6 years old, throwing feeble punches at a larger boy as he walked away, while other kids tagged along, some yelling. The scuffle took place off school grounds, after a game of pickup basketball. One kid insulted another kid’s mother, is what started it all.

The police were at Hobgood because of that video. But they hadn’t come for the boys who threw punches. They were here for the children who looked on. The police in Murfreesboro, a fast-growing city about 30 miles southeast of Nashville, had secured juvenile petitions for 10 children in all who were accused of failing to stop the fight. Officers were now rounding up kids, even though the department couldn’t identify a single one in the video, which was posted with a filter that made faces fuzzy. What was clear were the voices, including that of one girl trying to break up the fight, saying: “Stop, Tay-Tay. Stop, Tay-Tay. Stop, Tay-Tay.” She was a fourth grader at Hobgood. Her initials were E.J.

The confusion at Hobgood — one officer saying this, another saying that — could be traced in part to absence. A police officer regularly assigned to Hobgood, who knew the students and staff, had bailed that morning after learning about the planned arrests. The thought of arresting these children caused him such stress that he feared he might cry in front of them. Or have a heart attack. He wanted nothing to do with it, so he complained of chest pains and went home, with no warning to his fill-in about what was in store.

Also absent was the police officer who had investigated the video and instigated these arrests, Chrystal Templeton. She had assured the principal she would be there. She had also told Garrett there would be no handcuffs, that police would be discreet. But Templeton was a no-show. Garrett even texted her — “How’s timing?” — but got no answer.

Instead of going to Hobgood, Templeton had spent the afternoon gathering the petitions, then heading to the Rutherford County Juvenile Detention Center, a two-tiered jail for children with dozens of surveillance cameras, 48 cells and 64 beds. There, she waited for the kids to be brought to her.

In Rutherford County, a juvenile court judge had been directing police on what she called “our process” for arresting children, and she appointed the jailer, who employed a “filter system” to determine which children to hold.

The judge was proud of what she had helped build, despite some alarming numbers buried in state reports.

Among cases referred to juvenile court, the statewide average for how often children were locked up was 5%.

In Rutherford County, it was 48%.