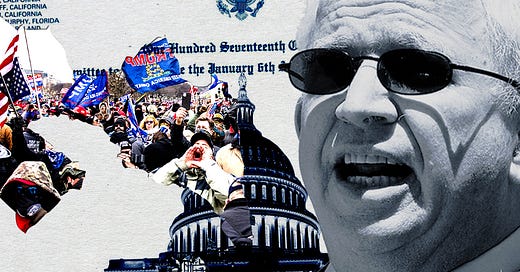

John Eastman’s Phony “Plenary Authority” Theory

How the Trump lawyer and Claremont scholar tried to convince Republicans they could overturn the 2020 election.

A curious and damning phrase has surfaced in the Jan. 6th hearings. The phrase is “plenary authority.”

Last Thursday, we learned that John Eastman, the law professor who conspired with Donald Trump to overturn the 2020 election, used this phrase to describe the vice president’s power in counting electoral votes. And at a hearing on Tuesday, we learned that Eastman used the same phrase to describe the power of state officials to choose electors.

“Plenary authority” means unlimited power. It means that Eastman was telling Vice President Mike Pence and Republican state legislators they could do whatever they wanted. It means that all the talk we heard over the years from Eastman and other Trumpists about respecting the Constitution was a complete joke.

Eastman has been preaching this faux humility his whole career. Three years ago, when the Heritage Foundation hosted a debate on originalism, he was brought in to present the affirmative case. He called for a strict reading of the Constitution, and he defended the standard conservative position, rebuking judges who “fill in” gaps in the Constitution “with whatever they want.” “The power to regulate commerce among the states meant it’s got to be commerce and it’s got to be among the states,” he argued. “It doesn’t mean I get to regulate the entire economy.” He warned that such loose, self-serving interpretations could lead not only to judges overstepping their roles, but also to “the legislature usurping their authorities.”

Eastman was right. In fact, he turned out to be the usurper.

At Thursday’s hearing, Greg Jacob, Pence’s former legal counsel, testified that in the days leading up to Jan. 6th, Eastman had lobbied him to overturn the election. “I started out with our points of commonality, or what I thought were our points of commonality,” said Jacob. “We’re conservatives. We’re small-government people. We believe in originalism.”

But Eastman wanted Jacob to betray those principles. He wanted Pence to abuse his ceremonial role in the electoral vote-counting process to reject many of Joe Biden’s electors. “He was pushing [a] robust unilateral power theory,” Jacob testified.

Jacob said that in their conversations, he reminded Eastman that the Constitution’s text gave the vice president no power over the electoral count. The Twelfth Amendment says only that the vice president, acting in his capacity as the president of the Senate, “shall . . . open all the certificates and the votes shall then be counted.” Jacob also pointed out that Eastman’s plan would violate the Electoral Count Act. But according to Jacob, Eastman replied “that we could do so because, in his view, the Electoral Count Act was unconstitutional.”

In short, Eastman wanted Pence to invent a power that wasn’t in the Constitution and, in the style of a judicial activist, assert that the Constitution overrode an act of Congress that stood in Trump’s way. All of this was fine, according to Eastman, because the vice president had the requisite “plenary authorities.”

That was bad enough. But on Tuesday, we learned that Eastman gave the same pep talk to Rusty Bowers, the Republican speaker of the Arizona House of Representatives. Bowers testified that in a phone call leading up to Jan. 6th, Eastman pressed him to “decertify” Biden’s electors in that state “because we had plenary authority to do so.”

Bowers said he couldn’t do that. He said that to claim such power would violate his oath of office. But according to his testimony, Eastman told him “that the authority of the legislature was plenary and that you can do it.”

This echoes the long version of Eastman’s coup memo to Trump: “Article II, § 1, cl. 2 of the U.S. Constitution assigns to the legislatures of the states the plenary power to determine the manner for choosing presidential electors.” According to that constitutional clause, “Each State shall appoint, in such Manner as the Legislature thereof may direct, a Number of Electors” who then select the president.

Of course, every state already has a process for selecting electors. What Eastman wanted Bowers and certain other GOP state legislators to do was to claim that the 2020 election was tainted, to halt their states’ electoral processes (which were complete except for the formalities), and to unilaterally override their states’ election results. This could be done by Republican majorities in state legislatures, Eastman asserted, since those legislatures had “plenary authority.”

When a politician wants to seize power, there’s always some legal theorist or would-be adviser who will tell him what he wants to hear. Trump found that voice in Eastman. And he used Eastman’s rationalizations to pressure others.

In their book, Peril, Bob Woodward and Robert Costa describe a meeting between Trump and Pence in the Oval Office on the eve of Jan. 6th. Trump wanted Pence to use his role in the electoral ceremony the next day to block the transfer of power. He asked Pence: “If these people say you had the power, wouldn’t you want to?” According to the book, Pence replied: “I wouldn’t want any one person to have that authority.” And Trump responded: "But wouldn’t it be almost cool to have that power?”

Many scholars and lawyers who talk about originalism are sincere. When they say that the Constitution limits the power of government and that it’s dangerous to expand that power through creative constitutional interpretations, they mean it. Jacob meant it. So did Michael Luttig, the revered former appellate judge who testified on Thursday that Trump’s attempted coup was an unconstitutional monstrosity.

But Eastman was never sincere. When the Constitution stood between him and power, all he cared about was power.