Judi Dench: Repaying Shakespeare

The legendary actress on why his work is timeless (and which play she can’t stand).

Shakespeare: The Man Who Pays the Rent

by Judi Dench with Brendan O’Hea

St. Martin’s, 375 pages, $32

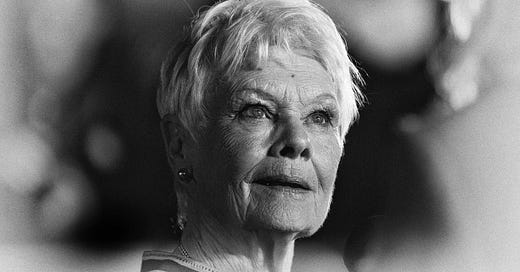

THIS BOOK IS A TROVE OF INSTRUCTION, amusement, lore, and wisdom. Originally, it was not intended to be a book at all, but a recording of conversations destined for everlasting obscurity in the archives of the Globe Theatre. The change of plan, triggered by the curiosity of a grandson’s friend, should be welcomed by all. Over the course of four years, Dame Judi Dench was interviewed about her career as Shakespearean actress with several distinguished theatre troupes and in three films, not counting her Oscar-winning turn as Queen Elizabeth in Shakespeare in Love. Her friend the actor and director Brendan O’Hea asked the questions, and the answers flowed copiously and often charmingly from the well-stocked mind of Dench, who will turn 90 next year, and who began her professional career as Ophelia at London’s Old Vic in the early 1950s.

Dench remembers damn near everything about the twenty Shakespeare plays in which she has appeared: She can recite whole scenes by heart; the apt quotation springs nimbly to mind to illustrate a point about language or character; the demeanor and antics of her colleagues, and sometimes even of audience members, vividly color her reminiscences; the hue and fabric of the costumes she wore remain permanently present to her powers of recall.

She knows Shakespeare intimately inside-out as surely as any scholar, but from an actor’s point of view. The best scholars deal mostly in analysis of themes, mining and sifting the language for big ideas, which Shakespeare undeniably supplied in abundance. Allan Bloom, who wrote excellent books about Shakespeare’s politics (with Harry V. Jaffa) and Shakespeare’s lovers, and who taught me more about how to read Shakespeare than any other teacher, went so far as to suggest that Shakespeare addressed and perhaps even answered every important human question. But as Dench says, “You can’t act a theme.” She has her own awed appraisal of Shakespeare’s wisdom. Of Mistress Quickly in Henry V feeling her way up Falstaff’s dead body (“and all was as cold as any stone”), Dench observes, “You just know Shakespeare’s been there—that he’s watched somebody die. Although he seems to have experienced everything, doesn’t he: what didn’t he know about?”

Bloom once said to me that actors are stupid, meaning that they don’t understand what the plays they are presenting are really about (largely because they tend to subscribe to the fashionable politics, and to pronounce correctly the cultural shibboleths, of the day), but they can do this marvelous thing that the rest of us can’t—give life to human beings who never existed except in a poet’s mind. At least in this case, Bloom was wrong: Dench used her uncanny instinct to embody Shakespeare’s women, and uses her ample intelligence to explain years later what she has done onstage.

The usual pressure of contemporary politics on the performing artist’s mind is often deleterious, but occasionally it can provoke a startling and useful insight. When the director Trevor Nunn was asked about a 1970s Royal Shakespeare Company production whether the Macbeths were the Nixons (the epitome, no right-thinking person can doubt, of crass ambition and ruthless grasping), the shrewdness of his reply brilliantly illuminated the play: “He said, ‘No, they’re the Kennedys.’ They’re the golden couple. They adore each other. And she’ll do anything for him. If he wants to be king, it will come to pass.” Dench perceives how this conjugal perfection with its erotic glamour at the outset prepares the way for Lady Macbeth’s shattering swift descent into loneliness, madness, and suicide. “She enabled Macbeth to murder Duncan because she thought that’s all it would require. But that wasn’t enough for him, and she can’t go any further with it. So he goes on and on and on, getting more voracious and ambitious, and she remains behind—alone. All’s spent.

“And that’s why I think she dies. Nothing exists of their marriage, which is why you have to establish how wonderful it is at the beginning.”

Dench is keenly aware how Shakespeare’s language can suggest with the utmost subtlety the hidden motions of a character’s mind. In Twelfth Night, Viola, a shipwreck survivor in an alien land, who for safety’s sake is pretending to be the young man Cesario, runs a romantic errand for Duke Orsino, trying to help convince the Countess Olivia to return his love. Viola has prepared a speech, but when Olivia removes her veil, the sight of her beauty suddenly rouses Viola to anger on Orsino’s behalf. Now when Viola speaks, it is no longer in witty prose but in foursquare blank verse:

’Tis beauty truly blent, whose red and white

Nature’s own sweet and cunning hand laid on.

Lady, you are the cruell’st she alive,

If you will lead these graces to the grave

And leave the world no copy.

Dench comments, “Yes, we’ve moved on from the repartee and verbal swordplay, and on to a bit of off-the-cuff truth. The words are no longer considered and rehearsed as they were before, but blurted out. She didn’t prepare that ‘’Tis beauty truly blent’ speech on the way there.” Dench agrees with O’Hea’s remark that blank verse possesses “the sound of sincerity,” and she dilates on that observation: “it’s plain speaking, straight from the heart, unfiltered. And Viola’s sincerity forces Olivia to open up.” Speaking confidentially, as if to a friend, Olivia insists there is no way for her to love Orsino. Olivia goes on to ask Viola how she herself would woo her beloved, and in her reply, Viola gets carried away by resounding ardor addressed explicitly to Olivia, but testifying whether she knows it clearly or not to “her own yearning for Orsino, which unwittingly bursts out of her. Because how else would you answer in that way? It’s so poetic and passionate, it’s such a ravishing speech.”

Like most performing artists, Dench takes pains to display her liberal good will. Sometimes Shakespeare riles her with the spectacle of human ugliness—most disturbing when characters who are largely good and even wonderfully attractive prove clearly flawed, especially by modern standards. Such are Portia and Bassanio in what Dench calls “The Merchant of fucking Venice,” “a horrible play”—though when pressed she does discern some virtue in these creatures of Shakespeare’s art. “One minute you’re delighting in their wit and rooting for them and the next you’re repelled by their racism and obsession with money. But maybe that’s what Shakespeare intended—for the audience to be conflicted, their sympathies forever shifting. I suppose it makes the characters more three-dimensional, complex and human, I just don’t want to be around them night after night, that’s all.”

DESPITE DENCH’S ROBUST EGALITARIAN STREAK—she professes herself baffled when a fellow movie actor finds it strange that she would eat lunch with her driver—her long Shakespearean immersion has made her an elitist in some crucial respects, and in the best way. The debasement of common parlance is cause for distress; where Shakespeare cavorted with the English language and enriched it many times over, coining words and memorable phrases in abundance, today many people find it next to impossible to get a coherent thought out. “My concern is how our language is becoming increasingly traduced, with the use of acronyms and emojis and people being incapable of uttering a sentence without using the word ‘like’ or ‘literally.’” The dumbing-down of Shakespeare’s own language by directors striving to leave no audience behind does not sit well with Dench: She wants no part of performing Shakespeare’s plays littered with some modern editor’s words.

Beauty matters, it matters immensely, and if beauty of this rarefied order is sometimes difficult to seize hold of, the performer and the audience will benefit from the effort. Dench closes her book with a democratically unexceptionable word of encouragement, which might seem anodyne and watery on its own but possesses moral gravity as the peroration to this series of conversations:

Shakespeare belongs to everybody. And we must allow who we are as individuals to colour our interpretation of his words: everybody’s upbringing and life experiences are different, and that needs celebrating and bringing to the plays. You’ve got to find out what his words mean for you.

Dame Judi Dench has spent much of her life making Shakespeare her own, and shaping her soul in the company of the Master; the result has been extremely gratifying to herself and to her audiences and readers.