RFK Jr. Stands in the Way of Polio Eradication

For just the second time in history, we have the opportunity to conquer a human virus—if we use the vaccines.

THE COVID PANDEMIC THAT REACHED our shores in winter of 2020 has taken more than 1.2 million American lives thus far—a staggering loss, on the one hand, and a tribute to modern medicine on the other. Until well into the twentieth century, the arrival and spread of infectious disease was met with panic, confusion, blame, flight, and ultimately resignation. A significant change occurred following the Second World War, with the development of antibiotics and vaccines for the treatment and prevention of everything from polio to measles, mumps, and tuberculosis. What made the COVID pandemic unique was the “warp speed” with which medical researchers and federal officials responded, working hand-in-hand to develop and manufacture safe and effective vaccines that revolutionized the field while saving untold millions of lives.

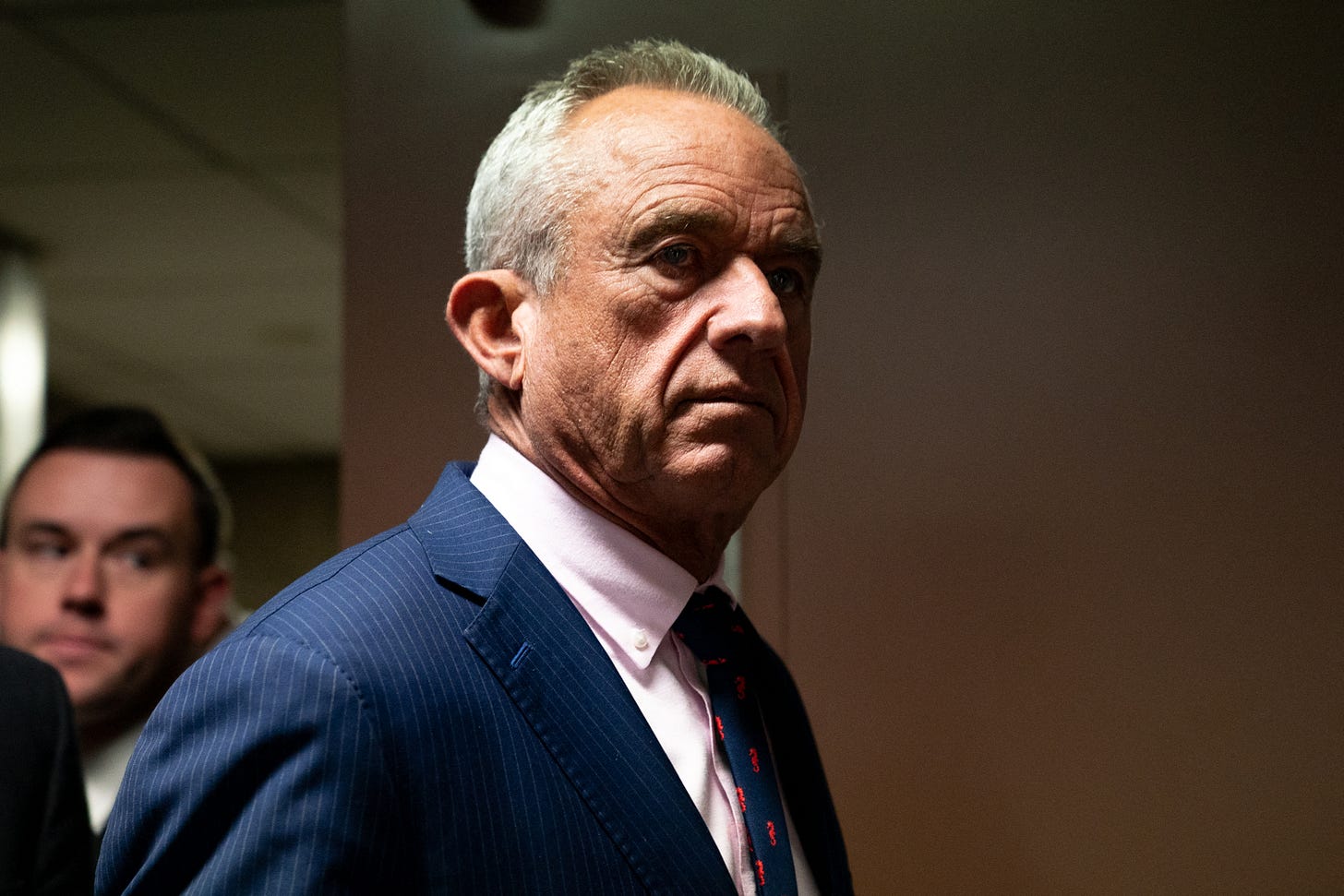

That’s what makes the confirmation of anti-vaccine activist Robert F. Kennedy Jr. for secretary of health and human services so troubling. Americans should be celebrating these milestones and demanding additional resources for the battles ahead. Instead, intense media scrutiny has provided a haul of previously unknown information about Kennedy and his organizations, including reports that a Kennedy confidant helping to vet candidates for high-ranking HHS positions had petitioned the Federal Drug Administration to withdraw its approval of the inactivated polio vaccine, which has stood for seventy years as the gold standard in the battle against infectious disease. Kennedy has called for a years-long “pause” on infectious disease research, and Elon Musk’s DOGE has frozen billions of dollars in federal grants for basic scientific and medical research.

Things could still get worse. Will junk science gain a serious foothold in decision-making bodies like HHS and its affiliated agencies? Will childhood vaccines now mandated by law become voluntary, or removed from circulation altogether? Putting a bullseye on the polio vaccine is a clear warning that even the safest, most proven vaccines aren’t safe from Kennedy.

BUT THERE’S MORE TO THE STORY. While the public health community is understandably fearful of attempts to undermine vaccination, there is, in fact, no consensus regarding the global campaign to eradicate polio. Some see it as an impossible task; others view it as a poor use of limited resources; still others believe that containment, rather than eradication, is the proper course.

There are two types of vaccines used to protect against polio: the injected killed poliovirus vaccine developed by Jonas Salk in the early 1950s, and the live oral poliovirus vaccine pioneered by Albert Sabin a decade later. In tandem, they have eliminated the disease in the developed world and come extremely close in the developing world. Reported cases of paralytic polio in the latter dipped from tens of thousands per year in the 1980s to fewer than two thousand by the early 2000s. Today that number is lower still, but global eradication remains elusive.

The campaign has been marred by a seemingly endless series of missed deadlines. In 1988, the World Health Organization and Rotary International, a remarkably generous private funder, resolved to end polio before the new century arrived. But problems arose that are yet to be fully solved. It had been known from the outset that the Sabin vaccine could revert to virulence in an infinitesimally small number of cases—about one in 750,000—primarily involving children with weakened immune systems. For that reason, the United States and most of the developed world went back to a more powerful version of the Salk vaccine in the 1990s, even though Sabin’s was cheaper and simpler to deliver.

By the early 2000s, the Sabin vaccine appeared to be causing more cases of paralytic polio in the developing world than the wild poliovirus still circulating there. But the numbers were so low, and the vaccine so vital for mass-vaccination campaigns in hard-to-reach places, that it remained the vaccine of choice. The compromise strategy was to use the live poliovirus vaccine, along with a robust surveillance system, to eliminate the transmission of wild poliovirus, at which point the inactivated poliovirus vaccine would be phased in to safely maintain immunity.

A sense of cautious optimism took hold by the first years of the millennium. Two prestigious journals, Nature and Science, ran article articles under the headlines “Polio’s Last Stand” and “Polio: The Final Assault?” In 2007, the Gates Foundation joined the cause, contributing more than $5 billion to the Global Polio Eradication Initiative over time. Each succeeding year began with the promise that “Polio eradication is within reach.” But fighting the disease became akin to a game of whack-a-mole: As soon as one area became polio-free, the virus would pop up in another. One observer described the effort as “trying to squeeze Jell-O to death.”

In 2011, Bill Gates called for a “final push” to eradicate polio during an event at the Manhattan townhouse of Franklin D. Roosevelt, a polio survivor, which I attended with great pride. A decade after promises of imminent victory, however, a sense of weariness and defeat had overtaken parts of the public health community. Donald A. Henderson, an iconic figure who had led the successful global campaign to eradicate smallpox in the 1970s, was not immune. Not only did Henderson portray the polio campaign as stuck in neutral, he also saw it as a zero-sum game in which the effort was sapping resources better spent elsewhere. “Fighting polio has always had an emotional factor—the children in braces, the March of Dimes posters,” he noted. “But it doesn’t kill as many as measles. It’s not in the top 20.”

Henderson’s complaints were echoed by others. “It’s theoretically possible to eradicate polio,” a WHO official declared. “Whether or not we can do it is an entirely another matter.” Bioethicist Arthur Caplan, a polio survivor, went a step further, saying that eradication was neither feasible nor essential: “We ought to admit that the best we can achieve is control.” And Richard Horton, long-time editor-in-chief of the Lancet, a leading medical journal, directed some withering criticism in Bill Gates’ direction. “[His] obsession with polio is distorting other priorities,” Horton said , adding: “Global health does not depend on polio eradication.”

Gates and his allies responded that any slowdown in the campaign would surely cause polio to spread, paralyzing and killing thousands of unvaccinated children. And Henderson did change his mind following conversations with his close friend, Dr. Ciro de Quadros, who had helped to eliminate smallpox and measles (temporarily) in parts of Africa and much of Latin America. What most impressed Henderson, he publicly admitted, was the ironclad commitment of Rotary International and especially the Gates Foundation to keep working and funding until the job was finished.

With the twenty-first century now entering its second quarter, the battle to eradicate polio is still in flux. There have been some major victories—India has been polio-free for almost a decade, a monumental task—but civil strife, religious zealotry, the murder of vaccinators, and fear of Western motives and medicine in remote areas have continued to impede mass vaccination programs. To compound matters, the Sabin vaccine requires a minimum of four doses to confer adequate immunity.

I FULLY UNDERSTAND THE SKEPTICISM toward eradication and the feeling that too much time, effort, and money have been directed toward a disease that pales, numerically, in comparison to other afflictions and public health problems. The global campaign to eradicate polio began with a burst of optimism that minimized or ignored dangerous hurdles, no doubt undermining its credibility. Over-promising is rarely a good idea, especially when that promise involves the elimination of an insidious childhood disease.

How close we are to fulfilling the mission remains in dispute. What is remarkable, however, is the tireless pursuit of the end game. Funding remains strong, the campaign continues to recruit millions of volunteers, and international cooperation, especially among Middle East and African nations, is clearly on the rise.

Trump’s decision to withdraw from the World Health Organization, coupled with his elevation of RFK Jr., has no doubt hurt the global eradication cause. But Trump himself has sent mixed signals. He recently spoke of friends who have battled polio, while describing the Salk vaccine as “the greatest thing ever,” akin to a miracle.

The battle must continue. Giving up on eradication would be a sign of defeat virtually guaranteed to increase the number of worldwide polio cases while conceding to the arguments of anti-vaxxers that the disease is unworthy of mandatory vaccination anywhere, including the United States. For those of us old enough to remember the scourge of polio before Salk and Sabin, it’s a sobering thought.