Lenin Is Still Dead—or Is He?

One hundred years later, Leninism is alive and kicking.

SUNDAY MARKED THE HUNDREDTH ANNIVERSARY of a death that, in its time, reverberated through the world: that of Vladimir Ilyich Lenin (né Ulyanov), the leader of the second Russian Revolution of 1917—the “October Revolution”— and the founder and first leader of the Soviet Union. “Lenin is dead, but his cause lives on” was one of the slogans plastered all over Soviet public spaces for much of the twentieth century. The Soviet Union ceased to exist in 1991, but Lenin’s ghost still haunts the world, much as the specter of communism haunted Europe in the famous opening lines of the Communist Manifesto. Today, Lenin’s open admirers are limited to marginal groups like the Young Communist League of Britain (whose house organ’s Twitter thread in praise of Lenin over the weekend was met with both outrage and derision). Yet far more mainstream leftwing publications such as Jacobin are still urging us to consider Lenin’s “complex legacy”—and over at the left/right hybrid Compact, Michael Cuenco argues that this legacy remains surprisingly relevant, and that Lenin’s ideological children may yet inherit the earth.

So, what is the legacy we are being asked to consider?

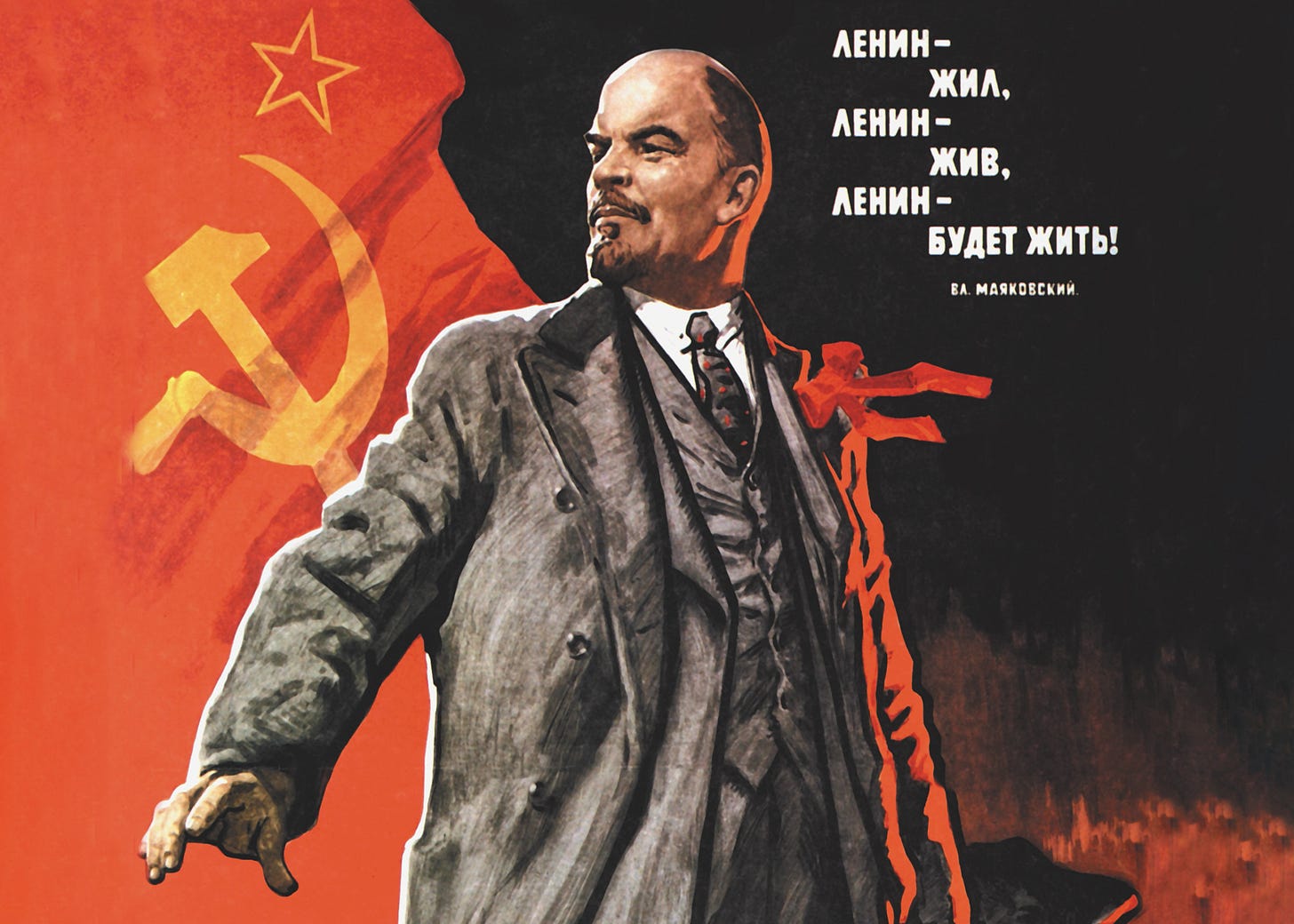

I GREW UP IN THE SOVIET UNION in the 1970s, when the Lenin cult, officially, was still in full force. I escaped the earliest influence of this cult because, unlike the vast majority of Soviet children, I never attended daycare; but once I was in school, “Grandpa Lenin” was everywhere. He was hailed as “the most humane of men”—an amalgam, in American terms, of George Washington and Jesus, with Jesus-like iconography that showed him surrounded by adoring children. (All the children in the world love Lenin/Because Lenin truly loved them all, said the lyrics of a Soviet song.) His dicta (Learn, learn, and learn!; Communism is Soviet power plus the electrification of the entire country; etc.) festooned the walls of every classroom, along with “Lenin forever” slogans such as the Christian-inspired Lenin lived, Lenin lives, Lenin will live. Even the music education classroom had a Lenin quote, from the memoirs of Russian-Soviet writer Maxim Gorky, praising Beethoven’s Appassionata as “amazing, superhuman music” (but leaving out the next part in which “the most humane of men” reflected that such music was a problem because it made you want to “pat people on the head” when the moment called for whacking them on the head—hard).

It’s hard to say how many people took the Lenin worship seriously. Lenin jokes were as ubiquitous as the Lenin cult, and often made fun of that cult—as in the joke in which a competition for the best monument to the great Russian poet Alexander Pushkin awards the third prize to a statue of Pushkin reading Lenin, the second prize to a statue of Lenin reading Pushkin, and the first prize to “just Lenin.” (This joke was almost literally reenacted at my school in 1974 when a poetry reading for Pushkin’s 175th birthday featured “poems about Lenin” along with poems by Pushkin, and the top overall honor naturally went to a girl who recited a poem from the first category.) Nonetheless, even many people with dissident leanings were inclined to see Lenin as the “good” Bolshevik, in contrast to bad Joseph Stalin. When Mikhail Gorbachev’s glasnost opened up the discourse on Soviet history, Lenin was the last to lose his halo.

Today, no one regards Lenin as “the most humane of men”; but progressive folks like those at Jacobin still cling to the myth that Lenin was essentially a democratic socialist. Jacobin’s interview with La Roche University historian Paul Le Blanc published for the anniversary of Lenin’s death includes the claim that Lenin “wanted a genuine democracy, not a phony democracy” and “felt that a lot of what passed for democracy was democracy for the rich at the expense of the poor.” Le Blanc suggests that the Soviet revolution’s “undemocratic swerve” was the result of the “devastating” experience of the Russian Civil War—which is another way of saying that the Bolsheviks only became violent because some people dared to oppose their coup. Seven years ago, an article in Jacobin commemorating the centennial of Lenin’s revolution likewise challenged those who depict Lenin as “authoritarian,” pointing out that after the Bolshevik takeover in November 1917, he initially allowed “legal rival parties” and “promoted the idea that workers’ and peasants’ organizations should be entitled to free press resources.”

But this is nonsense, easily refuted by a look at Lenin’s own writings—including many antedating the revolution. A 1906 Lenin article, “The Victory of the Cadets [Constitutional Democrats] and the Tasks of the Workers’ Party,” explicitly called for a revolutionary dictatorship, defined as “authority untrammeled by any laws, absolutely unrestricted by any rules whatever, and based directly on force,” exercised by “the revolutionary people.” In a 1908 article on the “lessons” of the 1870 Paris Commune, he wrote that one of its fatal mistakes was “excessive magnanimity on the part of the proletariat: instead of exterminating its enemies it sought to exert moral influence on them.” A 1903 Lenin essay titled “Revolutionary Adventurism” explicitly endorses “violence and terrorism in principle” as long as they are conducted in a way that guarantees “the direct participation of the masses.” (Lenin disapproved of nineteenth-century revolutionary terrorism—one acolyte of which had been his older brother, Alexander Ulyanov, hanged in 1887 for his role in a failed attempt on the life of Tsar Alexander III—because he considered it too isolated and inefficient.)

There are also some chilling accounts of Lenin telling political opponents, in pre-revolutionary days, exactly what he planned to do once he gained power. The Russian writer and activist Ariadna Tyrkova (later Tyrkova-Williams), who went to school with Lenin’s wife Nadezhda Krupskaya and visited her and Lenin in exile in Geneva in 1904, recalled one such moment in her memoirs. Lenin, then an ascendant leader in the Russian Social Democratic Labor Party (the Communist Party’s precursor), walked Tyrkova to a streetcar stop. On the way, he mocked her “liberalism” while she “teased” him about the Marxists’ desire to “force everyone into army barracks.” As they were parting, the future Soviet founder said with a nasty chuckle, “Just you wait, someday we’ll be hanging people like you from lampposts.” Tyrkova laughed it off, replying, “I won’t let you catch me”; Lenin retorted, “We’ll see about that.” Viktor Chernov, a leader in a rival leftist party, the Socialist Revolutionaries or “SRs”, had a somewhat similar anecdote from a few years later: When Chernov jokingly remarked that Lenin would start hanging Mensheviks (the rival Social Democratic Labor Party bloc) if he ever came to power, Lenin responded, “We’ll hang the first Menshevik after we’ve hanged the last SR.” (“Then he squinted and laughed.”)

Two recent definitive Lenin biographies, the one by British historian Robert Service published in 2000 and the one by Russian historian Dmitry Volkogonov published in 2013 and based on declassified Soviet archives, offer numerous examples of Lenin’s orders to carry out mass executions of “class enemies” such as priests and affluent peasants for purposes of intimidation. It was Lenin who created the Soviet state’s machinery of repression and terror that Stalin later perfected. As for press freedoms, Lenin’s 1921 letter to fellow revolutionary Grigory Myasnikov, who had called for a general liberalization of the Soviet regime and specifically for a free press, leaves no doubt as to where he stood. “We do not believe in ‘absolutes.’ We laugh at ‘pure democracy,’” wrote Lenin, explaining that “freedom of the press” was a great slogan when it enabled the struggle of the “progressive bourgeoisie” against “kings and priests, feudal lords and landowners.” On the other hand,

Freedom of the press in [Soviet Russia], which is surrounded by the bourgeois enemies of the whole world, means freedom of political organization for the bourgeoisie and its most loyal servants, the Mensheviks and Socialist Revolutionaries. [It] means facilitating the enemy’s task, means helping the class enemy.

We have no wish to commit suicide, and therefore, we will not do this.

It is also worth noting that Lenin took inspiration from the French Revolution’s most radical phase: the Reign of Terror. (Terror ideologues Jean-Paul Marat and Maximilien Robespierre were both treated as revolutionary icons in the Soviet Union from its earliest days.) But Lenin’s revolution raised terror to a whole new level of obscenity. While his eighteenth-century French idols executed the king and queen of France after public trials with at least a semblance of due process, the Russian royal family was gunned down in a basement, in an orgy of slaughter that included the tsar and tsarina’s five children, family doctor, three personal attendants, and pet spaniel. Historians disagree on whether Lenin personally gave the order for the execution of the royal family and retinue, but Volkogonov points to some of the evidence suggesting that he did: “The object of ‘exterminating the entire Romanov kin’ is confirmed by the almost simultaneous murders” of six other nobles of the Romanov house, “all of them in Alapaevsk, a hundred miles from Yekaterinburg,” where the royal family was murdered.

Unlike Stalin, Lenin was not a sadist; he saw terror as a pragmatic instrument, not a dark comedy for his enjoyment. (It’s difficult to imagine him laughing uproariously at a henchman’s reenactment of a condemned former ally’s last-minute pleas for mercy, as Stalin is said to have done at the report of Grigory Zinoviev’s execution.) But Lenin was the walking trope of the “friend of humanity” for whom actual human compassion matters only when convenient. He manifested this in both action and inaction: Service reports that in 1891–92, when famine, cholera, and typhus struck the Volga region of Russia, Vladimir Ulyanov—then a barrister, small landowner, and budding revolutionary—not only staunchly opposed all famine relief efforts but refused to reduce rents for the tenants on his estate there. His own devoted sisters were shocked. For Lenin, however, the answer was clear: compassion could only retard revolution and undercut the essential task of discrediting both tsarism and capitalism.

IN VLADIMIR PUTIN’S RUSSIA, Lenin is viewed through the same schizophrenic lens as the rest of Russian and Soviet history: He is both blamed for undermining the Russian Empire and defended against critics of the Soviet empire. This paradox is exemplified by the fact that, while Putin has blamed Lenin and his Bolsheviks for creating an independent Ukraine and for planting a “time bomb” under Russia’s foundations, Ukrainian cities occupied by Russian troops have seen previously removed Lenin monuments restored and street names reverting to Soviet-era ones honoring Lenin.)

Outside Russia, Lenin’s legacy is similarly confused. Cuenco’s Compact article argues that Xi Jinping’s China, which combines aggressive ideological control with a quasi-capitalist economy, represents the flourishing of Lenin’s “New Economic Policy,” designed to harness market forces in the service of the Soviet state. One could even view China’s conquest of Western markets in light of Lenin’s reported (though unauthenticated) prediction that “the capitalists will sell us the rope with which to hang them.”

Meanwhile, some Western progressives are still reluctant to cut Lenin loose, even though he represents left-wing radicalism at its worst. According to Russian historian Nikita Sokolov, his only consistent conviction was a fundamental belief in “violence as the solution to any problem.” He was a man who regarded freedom as a nuisance and human suffering as an abstraction, who advocated for “the masses” but argued that only an elite revolutionary “vanguard” could properly express those masses’ interests, who was very much in favor of bourgeois comforts for himself and his friends, and preached equality for women but relied on the self-abnegating devotion of female family members to fuel his career.

Lenin also has his rightwing admirers of sorts. In his Compact article, Cuenco mentions such “American Leninists” as Steve Bannon and Christopher Rufo—that is, Leninists of “style and temperament rather than ideology.” Bannon has reportedly likened himself to Lenin in wanting to “bring everything crashing down and destroy all of today’s establishment.” Rufo hasn’t explicitly invoked Lenin but, in the view of conservative commentator Mary Harrington, borrows from “the Leninist idea of ‘vanguardism’” in advocating a conservative crusade to seize control of “woke” institutions.

Perhaps, in the most fundamental sense, a “Leninism of style and temperament” means an outlook that reduces politics to Lenin’s famous “who, whom?”—i.e., who will prevail in a power struggle—and treats the “other side” as an enemy to be destroyed or subjugated. In that case, Leninism is a clear and present danger in American life, and Lenin’s ghost still haunts the world a hundred years after his death.