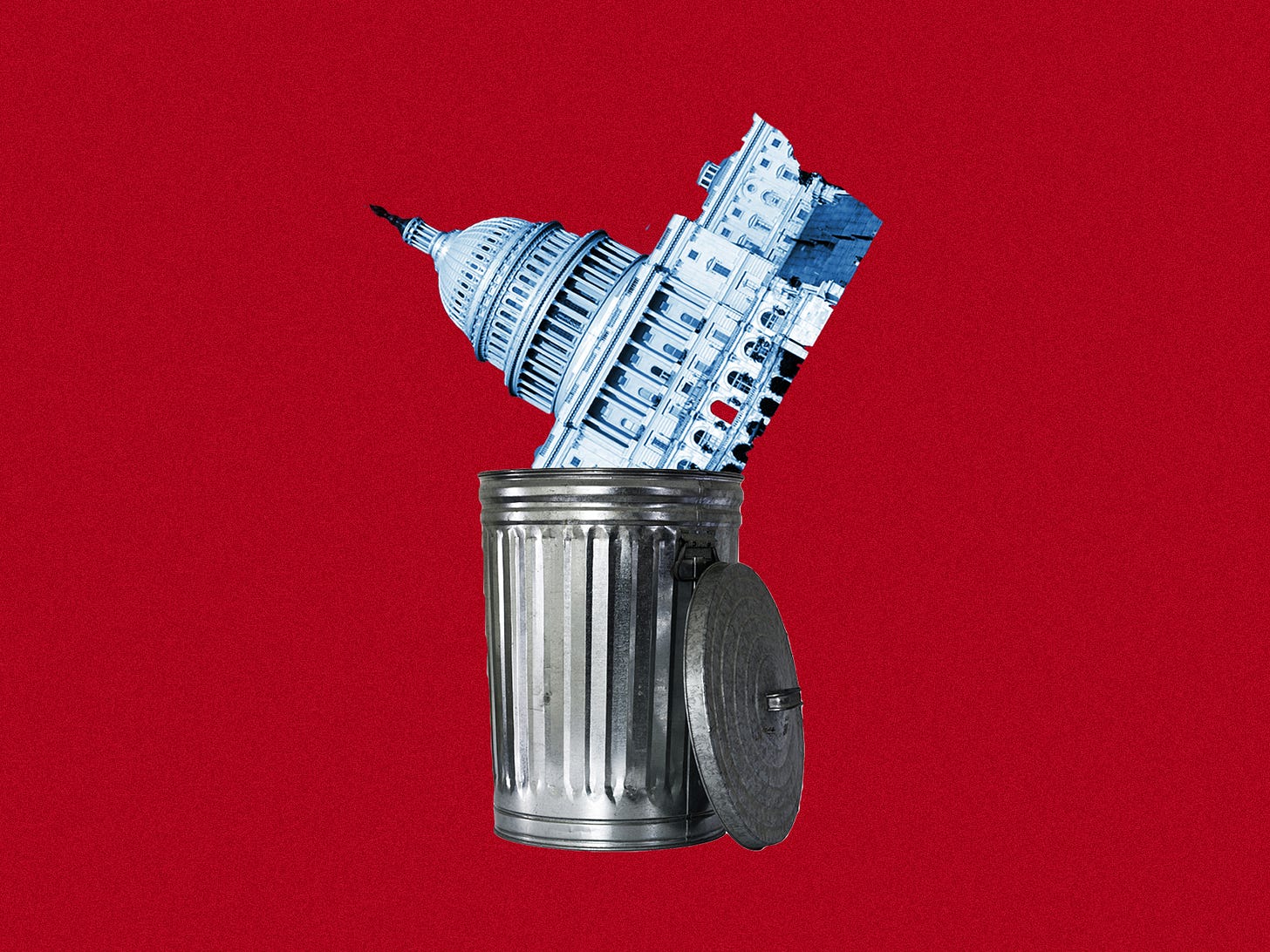

Let’s Maybe Not Trash the ‘Establishment,’ OK?

Trump promised to drain the swamp, but he's only made it worse. And now Democrats are running against the establishment, too. That’s a bad idea.

When Steve Bannon explains the “populist revolt” he helped launch in the United States (in this debate with David Frum, for instance, or in this address to the Oxford Union), he points to what he regards as the most egregious elite failures in the 21st century. From a “financial crisis brought about by a financial elite that’s never been held accountable” to “wars that we didn’t win” in Afghanistan and Iraq, Bannon thinks the political establishment in the United States has a lot to answer for, and Donald Trump is its reckoning.

That leaves him in interesting company. Noam Chomsky was interviewed by The Nation in the summer of 2017, and he argued that Trump, Brexit, and the rise of nationalist movements around the world were all symptoms of much larger problems: “When you impose socioeconomic policies that lead to stagnation or decline for the majority of the population, undermine democracy, remove decision-making out of popular hands, you’re going to get anger, discontent, fear...” Even though Chomsky says this phenomenon is “misleadingly called ‘populism,’” those observations could have been lifted straight out of one of Bannon’s speeches.

While Bannon and Chomsky have radically different ideologies, their diagnoses of the anger, discontent, and fear that have crept into Western politics are remarkably similar. They both talk constantly about working and middle class wage stagnation. They both condemn an economic system increasingly dominated by finance—what Bannon describes as the maximization of shareholder value instead of citizenship value. They both accuse a small ruling class of disregarding the interests of the majority of the population in pursuit of ever-increasing concentrations of wealth and power. And most of all, they despise what they regard as the guiding ideology of the postwar political establishment.

For Chomsky, that ideology is “neoliberalism,” which he describes as “an array of market oriented principles designed by the government of the United States and the international financial institutions that it largely dominates”—principles that “undermine education and health, increase inequality, and reduce labor’s share in income.”

According to Chomsky, neoliberalism even threatens the survival of our species. In his conversation with The Nation, he points to the “two existential threats that we’ve created” (nuclear weapons and climate change) and blames neoliberalism for “eliminating, or at least weakening, the main barrier against these threats.” This barrier is “an engaged public, an informed, engaged public acting together to develop means to confront the threat and respond to it.” But the establishment wants people to “become more passive and apathetic and not to disturb things too much, and that’s what the neoliberal programs do.”

While Chomsky uses “neoliberal” to describe what he sees as the worst elements of the political and economic status quo, Bannon uses equally vague epithets like “Party of Davos.” Here’s a typical Bannonism: “What we’ve become with this permanent political class … this Party of Davos has turned us into an expeditionary humanitarian force.” From the overextension of American power to the “fetish” of the “post-war international rules-based order,” the Party of Davos is always the culprit. Like Chomsky, Bannon has managed to fit everything he doesn’t like under a single neat little heading.

“Neoliberal” is one of those words, like “globalist” or “elite,” that’s almost always used as a sneer. How many politicians and intellectuals actually call themselves “neoliberals”? How many consciously pursue or defend what they would describe as neoliberal policies? The looseness of the word is what makes it so useful for anyone who advocates a radical departure from the status quo, whether on the right or the left. By condemning the “system” or the “Washington consensus”—intentionally amorphous terms that encompass just about everything—ideologues can make a case that sweeping, fundamental change is necessary.

It’s useful to have someone to blame for virtually every political and social problem. As Trump’s campaign demonstrated, scapegoating can be a powerful tool—immigrants were sneaking into the country, stealing jobs, and committing crimes; other countries were “laughing” at the United States and undermining the American workforce with one-sided trade deals and exploitative international agreements; and the elites had nothing but contempt for the working class. We’re seeing a similar phenomenon with the rise of the populist left, but the scapegoats are wealthy Americans and a political establishment that has become too friendly with influence-peddling oligarchs. As Elizabeth Warren put it in her announcement speech, she’s fighting against a “rigged system that props up the rich and the powerful and kicks dirt on everyone else.”

There’s a reason words like “system,” “consensus,” “establishment,” “elite,” “political class,” “status quo,” etc. are so politically effective. For one thing, they include both major parties. One of the reasons Trump was so successful in the primaries was the fact that he seemed to reject the Republican consensus on so many issues—particularly trade and foreign policy.

If anything, establishment opposition to Trump (whether in the form of open letters from GOP national security leaders or stern rebukes from Mitt Romney) helped him solidify his image as the agent of change Washington needed. When Trump was elected, only 32 percent of Americans thought the country was on the “right track”—a number that was even lower during the campaign. Bannon often cites this as the only measure he cared about—as long as Americans thought the country was on the “wrong track,” Trump’s message would continue to resonate.

During the general election, when Trump was running against someone who embodied the political establishment that so many Americans loathed, his outsider image helped him even more. Meanwhile, many left-wingers (particularly Sanders supporters) decided to stay home on Election Day instead of casting their votes for yet another corrupt neoliberal. According to FiveThirtyEight’s analysis of a SurveyMonkey poll of 100,000 registered voters, “Donald Trump probably would have lost to Hillary Clinton had Republican- and Democratic-leaning registered voters cast ballots at equal rates.” One of the reasons for this gap was the fact that a huge number of young minority voters didn’t go to the polls – including 46 percent of young black voters, who were more likely to support Sanders.

While it’s impossible to know exactly what accounts for the number of voters who didn’t turn out in 2016, it isn’t difficult to imagine that a general anti-establishment bias was one of the most important factors. Which brings up an obvious question: Shouldn’t this serve as a warning? No matter how justified the anger toward neoliberalism, the Party of Davos, etc. happens to be, isn’t there a risk that the countervailing forces of populism and ideology will create even bigger problems?

The establishment doesn’t have many fans these days. According to Pew data, public trust in government has been collapsing since the middle of the twentieth century. While there was a resurgence in trust throughout the 1990s and at the beginning of the 21st century, it fell from 54 percent in October 2001 to just 18 percent in December 2017. These numbers suggest that Bannon and Chomsky’s diagnosis is right – decade after decade of frustration with the establishment opened the way for a subversive candidate like Trump.

But Trump hasn’t been the transformative figure he promised to be. As Scott Sumner explained in a recent article for EconLog (titled “Is neoliberalism dead?”): “Neoliberalism is indeed rapidly losing support among intellectuals on both the left and the right. But there is almost no evidence that countries are going to actually walk away from neoliberal policy regimes.” He points to Trump’s support for the GOP’s tax plan, which is “about as neoliberal a policy as one could imagine.” It’s difficult to see how Bannon reconciles his anti-elitism with the fact that the Party of Davos is well represented in the Trump administration—Trump’s Cabinet is stuffed with more millionaires and billionaires than any Cabinet in modern history.

With Trump, we get a perpetuation of all the establishment’s problems with none of its stability – the Washington consensus with the added chaos of an erratic and corrupt demagogue in the Oval Office. It’s true that the political status quo in the United States has become more and more dysfunctional over the past few decades—just look at the fact that government shutdowns have become routine negotiating tools (the most recent one was the longest in American history) or the surging level of polarization in Congress. But all the anti-establishment fury on the Left and the Right didn’t give us revolution or reform —it just gave us Trump.

You’d think this outcome would occasion a little modesty, but it has had the opposite effect. To the people who hate the establishment, Trump is just more evidence that the establishment is rotten. Chomsky now describes the GOP as the “most dangerous organization in world history.” Bannon is running around Europe trying to start a continent-wide populist revolution. Trump’s presidency has only emboldened anti-establishment forces in the United States, which is why populist figures like Warren and Sanders launched their presidential campaigns with fiery denunciations of the “system” and the “powerful special interests that dominate our economic and political life.”

Sanders decries Trump as the “most dangerous president in modern American history … a president who is a pathological liar, a fraud, a racist, a sexist, a xenophobe, and someone who is undermining American democracy as he leads us in an authoritarian direction.” But if he hadn’t run for president in 2016, there’s a good chance that Democrats would have been more united around Clinton and Trump wouldn’t be in office right now. This isn’t to say Clinton’s brand of politics is attractive—it’s just an acknowledgment of political reality.

With well-known populist candidates like Sanders and Warren in the 2020 race, the broad outline of the Democratic primary is already clear: There will be another battle between the progressive and establishment wings of the party. This will hobble the victor going into the general election and may end up handing Trump a second term. Then we’ll all get another excruciating four-year reminder that there are worse things in the world than the establishment we’ve all learned to despise.