I know you want to talk about the January 6 commission stuff. But there’s a lot of that out there already and I’ll have stuff to say about it tomorrow.

Instead, I want to swerve. So bear with me.

And if you’re new here and this sort of thing interests you, I hope you’ll sign up to get more from The Bulwark.

1. Little Green Men

Here is a true story: Once upon a time the sitting governor of the Great State of Georgia talked about seeing a UFO. This man would go on to be elected president of these United States, because no one thought UFO talk was crazy. It was firmly within the cultural mainstream.

People forget that. In the 1960s and 1970s, the subject of UFOs was totally acceptable. Chariots of the Gods sold 70 million copies. In Search Of was a societal touchstone. Project Blue Book and Area 51 and SETI were part of the lexicon.

The responsible, grown-up view was that UFOs were real, in the sense that what people were seeing were actual things that we could not identify. Maybe they were test aircraft. Maybe they were visual phenomena. Some of them were surely hoaxes. But not all of them. And that eventually, some day, as science advanced and government files were declassified, we’d be able to put labels on these things.

The more fanciful view was, well . . .

Somewhere along the way—probably starting in the mid-1980s—the subject of UFOs moved decidedly outside the mainstream. So much so that in 2005, if you were talking about UFOs then the world basically assumed you were that guy.

I have lots of theories for why this shift took place. The big one is: the Internet.

You might have thought that the internet would be a cultural accelerant for ufology. That it would bring UFO people together and help them share information. But in practice, it turned out to have a different effect. The internet siloed off UFO interest from the rest of the culture.

And on a bigger, societal scale, the internet turned our gaze inward.

For decades, all of the big, interesting stuff was out there. The moon. The stars. Rocketry. The space race. The Apollo missions. The Voyager project. Space was our frontier.

But with the advent of the internet, we turned inward. All of the interesting stuff was small terrestrial. Today, all of the interesting stuff is literally on your phone. The frontier is us.

Which made all of that UFO business exotic. And exotic is another word for weird.

2. We Stopped Looking; But They Never Went Away

Here is another true story: Ten years ago I was going to write a piece about this phenomenon—how the internet had displaced space in the popular imagination and the effect this shift had on ufology in the culture.

I was introduced to a gentleman as a source. Incredibly smart man. A psychiatrist. I was told that he knew a great deal about UFO culture. I took him to lunch to see what he could tell me about the kind of people who believe in UFOs.

It turned out that he believed in UFOs. And not just believed in them, but had seen one. He described the experience to me in great detail.

My friend was not part of the Little Green Men caucus. He explained that, yes, many sightings were hoaxes. And that many sightings could be explained by available information. He wouldn’t rule out alien technology as an explanation, but he believed the more likely answer was that it was advanced human technology that had not yet been made public.

Talking with him was like jumping back in time to 1975, when discussing UFOs didn’t automatically mark you as a nutter.

It’s possible that today we’re entering a new phase of ufology.

I know there’s a lot going on in the world. Global pandemic. Political turmoil. The long march to the universal DH.

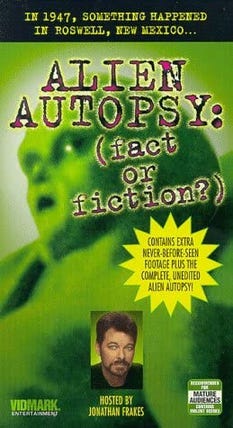

But the Pentagon is close to issuing a new report on UFOs and you don’t have to be Jonathan Frakes to see it as a BFD.

Look, I can quote you the Fermi Paradox backwards and forwards. If you want to nerd really hard, we can talk about the technological challenges of interstellar travel. In order to travel between the stars, a civilization would need to either:

Master FTL technology, or

Be able to warp space/time

(Or possibly do some sort of magic with quantum entanglement, though this is a much longer shot. Don’t @ me Peter Hamilton.)

Which is to say that I view the alien explanation with a great deal of skepticism and I am not prepared to go full Little Green Men.

But on the other hand, we only have a couple options here. The decision tree goes like this:

There’s nothing there; all of these sightings are hoaxes, or tricks of light, or explicable by natural phenomena; or

There’s something there.

And if you take the something branch, then you have to pick from a list of highly unlikely explanations:

Secret technology being run by the American government.

Secret technology from a foreign government.

Secret technology from a non-state actor.

Aliens.

I don’t know about you, but of those four, it’s not clear to me which explanation would be the most worrisome.

Okay, I lied. I know exactly which explanation would scare me most.

3. Taking UFOs Seriously

From the New Yorker:

On May 9, 2001, Steven M. Greer took the lectern at the National Press Club, in Washington, D.C., in pursuit of the truth about unidentified flying objects. Greer, an emergency-room physician in Virginia and an outspoken ufologist, believed that the government had long withheld from the American people its familiarity with alien visitations. He had founded the Disclosure Project in 1993 in an attempt to penetrate the sanctums of conspiracy. Greer’s reckoning that day featured some twenty speakers. He provided, in support of his claims, a four-hundred-and-ninety-two-page dossier called the “Disclosure Project Briefing Document.” For public officials too busy to absorb such a vast tract of suppressed knowledge, Greer had prepared a ninety-five-page “Executive Summary of the Disclosure Project Briefing Document.” After some throat-clearing, the “Executive Summary” began with “A Brief Summary,” which included a series of bullet points outlining what amounted to the greatest secret in human history.

Over several decades, according to Greer, untold numbers of alien craft had been observed in our planet’s airspace; they were able to reach extreme velocities with no visible means of lift or propulsion, and to perform stunning maneuvers at g-forces that would turn a human pilot to soup. Some of these extraterrestrial spaceships had been “downed, retrieved and studied since at least the 1940s and possibly as early as the 1930s.” Efforts to reverse engineer such extraordinary machines had led to “significant technological breakthroughs in energy generation.” These operations had mostly been classified as “cosmic top secret,” a tier of clearance “thirty-eight levels” above that typically granted to the Commander-in-Chief. Why, Greer asked, had such transformative technologies been hidden for so long? This was obvious. The “social, economic and geo-political order of the world” was at stake.

The idea that aliens had frequented our planet had been circulating among ufologists since the postwar years, when a Polish émigré, George Adamski, claimed to have rendezvoused with a race of kindly, Nordic-looking Venusians who were disturbed by the domestic and interplanetary effects of nuclear-bomb tests. In the summer of 1947, an alien spaceship was said to have crashed near Roswell, New Mexico. Conspiracy theorists believed that vaguely anthropomorphic bodies had been recovered there, and that the crash debris had been entrusted to private military contractors, who raced to unlock alien hardware before the Russians could. (Documents unearthed after the fall of the Soviet Union suggested that the anxiety about an arms race supercharged by alien technology was mutual.) All of this, ufologists claimed, had been covered up by Majestic 12, a clandestine, para-governmental organization convened under executive order by President Truman. President Kennedy was assassinated because he planned to level with Premier Khrushchev; Kennedy had confided in Marilyn Monroe, thereby sealing her fate. Representative Steven Schiff, of New Mexico, spent years trying to get to the bottom of the Roswell incident, only to die of “cancer.” . . .

The government may not have been in regular touch with exotic civilizations, but it had been keeping something from its citizens. By 2017, Kean was the author of a best-selling U.F.O. book and was known for what she has termed, borrowing from the political scientist Alexander Wendt, a “militantly agnostic” approach to the phenomenon. On December 16th of that year, in a front-page story in the Times, Kean, together with two Times journalists, revealed that the Pentagon had been running a surreptitious U.F.O. program for ten years. The article included two videos, recorded by the Navy, of what were being described in official channels as “unidentified aerial phenomena,” or U.A.P. In blogs and on podcasts, ufologists began referring to “December, 2017” as shorthand for the moment the taboo began to lift. Joe Rogan, the popular podcast host, has often mentioned the article, praising Kean’s work as having precipitated a cultural shift. “It’s a dangerous subject for someone, because you’re open to ridicule,” he said, in an episode this spring. But now “you could say, ‘Listen, this is not something to be mocked anymore—there’s something to this.’ ”

Since then, high-level officials have publicly conceded their bewilderment about U.A.P. without shame or apology. Last July, Senator Marco Rubio, the former acting chairman of the Select Committee on Intelligence, spoke on CBS News about mysterious flying objects in restricted airspace. “We don’t know what it is,” he said, “and it isn’t ours.” In December, in a video interview with the economist Tyler Cowen, the former C.I.A. director John Brennan admitted, somewhat tortuously, that he didn’t quite know what to think: “Some of the phenomena we’re going to be seeing continues to be unexplained and might, in fact, be some type of phenomenon that is the result of something that we don’t yet understand and that could involve some type of activity that some might say constitutes a different form of life.”