Long Before Hungary, the Right Was Fixated on Another Country

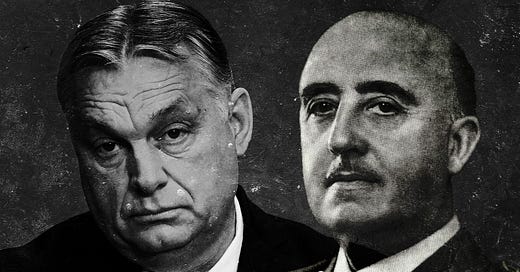

Just as they’re now doing with Viktor Orbán, conservatives once fell head over heels for Francisco Franco.

Prominent conservatives have discovered Hungary and its “twenty-first century dictator,” Viktor Orbán. This week, Tucker Carlson will be relocating his top-rated show to Hungary, as he did for a week last August, bringing Orbán into the homes of hundreds of thousands of Fox viewers.

Carlson may be the most high-profile conservative to alight on Hungary, but he’s far from the first. Christopher Caldwell profiled Orbán in the Claremont Review of Books in 2019; former National Review editor John O’Sullivan moved to Budapest, where he has run the Danube Institute, a think tank funded by Orbán’s government, since 2017; the American Conservative’s Rod Dreher spent four months last year in Budapest under the auspices of the Danube Institute, largely singing its praises; while a number of others, including Patrick Deneen, Chris DeMuth, Sohrab Ahmari, Yoram Hazony, and Jordan Peterson have made pilgrimages, in several cases meeting with Orbán himself. Early this year, Donald Trump endorsed Orbán for re-election.

Hungary’s appeal to the American right is straightforward. Among the world’s leaders, Tucker Carlson pronounced, only Orbán identifies as a Western conservative. He takes pride in standing athwart European Union integration, internationalism, immigration, and “wokeism.” He champions the Hungarian nation and the Christian West.

While Republican politicians like Ted Cruz and Josh Hawley muse that “the left hates America” and its “grand ambition is to deconstruct the United States of America,” Hungary suggests another path—one where the right, apparently harnessing popular energies, wields the state against the cultural left, evidenced by Hungary’s anti-LGBTQ law and its defunding of gender studies programs in Hungarian universities. For American national conservatives already abandoning small-government positions, Orbán fuels dreams of an American right brandishing the power of the federal government. Others may see in Hungary a hint of “integralism”—the possibility of a Christian state integrated under the governance of the Catholic Church.

Sometimes Orbánphilia on the American right is accompanied by modest finger-wagging about his corruption or overreach, such as his use of surveillance technology against journalists. But the American right is at minimum anti-anti-Orbán, and frequently celebratory. His admirers contrast his use of Hungarian state power positively with the perceived coercive power of progressivism. If we “are going to mount an effective political resistance to the soft totalitarianism taking over our country,” writes Dreher,

then we are going to have to have aggressive, competent, national conservative leadership, one that is not averse to intervening in the economy for the sake of the common good. The best example of that now on the world stage is Viktor Orbán.

Despite his obvious enthusiasm, Dreher played somewhat coy when interviewed for an October New York Times magazine article on Orbán and his American admirers. Dreher portrayed his interest in Hungary as intellectual or journalistic, assessing the “extent politics can be a bulwark against cultural disintegration,” asking “what is the cost, and is the cost worth it?”

Since these questions coincide with a recent broader curiosity about historic right-wing strongmen, it is worth taking a moment to reflect on the American right’s relationship with another dictatorship—a story that has largely been forgotten with the passing of the generations.

For a relative European backwater, Francoist Spain figures prominently in the history of American intellectual conservatism. National Review, the conservative journal of ideas that emerged from both right-wing and Catholic circles in the mid-1950s, reflexively defended both the Franco of the contemporary 1950s and the victory of the Nationalists over the secular Republican government in the Spanish Civil War in the 1930s.

With their own Spanish-language skills, and with Spain’s low cost of living, Catholic culture, and right-wing government, important conservative writers—L. Brent Bozell, Willmoore Kendall, and Frederick Wilhelmsen—lived in Spain during critical periods of intellectual development. Likewise, conservative luminaries William F. Buckley, Jeffrey Hart, James Burnham, Erik Kuehnelt-Leddihn, and Russell Kirk all ventured to the dictatorship. Buckley’s brother Reid spent fifteen years in Spain writing novels as well as romantic accounts of life in Madrid for National Review under the pseudonym Peter Crumpet.

These intellectuals were never as close to Franco as contemporary conservatives are to Orbán. In fact, hardly born democrats, they frequently called for a restored monarchy to succeed Franco, scoffing at the idea of democracy in Spain.

Nevertheless, there are striking parallels. As with the current relationship with Hungary, the conservative experience of Spain was characterized by celebrations of the Nationalist victory against leftist “aggression,” anti-anti-Franco apologia, and rethinking conservative dogmas in the shade of Spanish cathedrals.

Sketches of Spain

“General Franco is an authentic national hero,” William F. Buckley wrote from Spain in 1957. Franco wrested the country “from the hands of the visionaries, ideologues, Marxists, and nihilists that were imposing upon her, in the thirties, a regime so grotesque as to do violence to the Spanish soul, to deny, even, Spain’s historical identity.” Unsurprising sentiment from the devout Buckley. But he criticized the Franco regime for outliving its welcome and failing to establish true legitimacy.

National Review walked a careful line of critiquing and justifying Franco, while celebrating the conservative Spanish character and the wartime Nationalists.

The stark terms of the Cold War overshadowed everything. Conservatives understood the Spanish Civil War—the defining question for Franco’s legacy—as an existential conflict between communism and Christendom. “What would have happened had Communism won in Spain?” asked one pro-Nationalist writer in National Review, reducing the complex conflict to a binary choice. Another concluded in the mid-1960s that, however much Franco lacked in magnanimity, the Communist coup would mean the “merciless, imposed rigidity of another neo-Stalinist state.” “It was better that Franco won.”

Others tightly linked Spanish liberalism with communism. Francis Wilson endorsed the thought of a Spanish rightist intellectual who argued that liberalism inevitably paved the way to communism. Russell Kirk wrote that “one cannot really understand the Spanish Civil War without knowing something about liberalism.” Numinously, Buckley updated a medieval myth: Rumors in Spain claimed its patron saint, James the Apostle, had manned a Nationalist gun post as the “Republican juggernaut” sought to relieve the siege of Madrid. Less piously, hardnosed editor Jeffrey Hart in 1966 described Spain’s Civil War as the “prototype of a new style” of “internationalized civil war” that saw Yugoslavia, Greece, Cuba, and Vietnam—and American responses to them—divide along the same cultural and intellectual lines.

Likewise, National Review defended Franco’s Spain from “World Opinion” (“merely the expression of the dogmas of the Libintern, the international apparatus of the Establishment,” joked historian Jefferson Davis Futch III). Elsewhere, the magazine cheered Franco’s foreign minister Fernando María Castiella’s 1960 visit to America where the Spaniard shot down media critics. NR waved away Castiella’s service in the Blue Legion—a Spanish volunteer force fighting alongside Nazi Germany in the Second World War—as “a disquieting partnership, heaven knows.” But, wrote the editors, he acquitted himself well in New York, reminding the press that “more than half my generation died in Spain twenty years ago defending the ideas of the Christian Faith in a Civil War which to us was a Crusade.”

It wasn’t just Franco’s Spain itself that conservatives lauded, but even glowing depictions of it. Russell Kirk in 1964 depicted the popular Spanish Pavilion at the New York World’s Fair as “a triumph of traditionalism alive in the modern age” and a “symbol of Liberalism’s decay.”

More broadly, NR routinely rejected charges of Francoist fascism, touted Spain as a NATO ally, and responded to criticism of the regime. Could Spain catch a break, NR wondered, for the “sin” of “opposing a Communist takeover” a quarter century earlier?

Like today’s right and Hungary, the conservative mainstream had criticisms of Franco and his government, while remaining anti-anti-Franco. “Spain has the most elaborate system of social security outside of New Zealand,” chided NR’s roving European contributor Erik Kuehnelt-Leddihn. Like Orbán, Franco permitted enormous corruption; the biggest threat to Franco’s rule was “his misgovernment, his laziness, his socialistic paternalism, his indifference not to freedom but to corruption,” reported Buckley. The New Conservative Francis Wilson suggested that the Francoist Falange Party had become more Tammany Hall than transformative.

To be sure, these were conservative critiques, focused on Spain’s economics, foreign policy, and corruption. In 1959, Kuehnelt-Leddihn bemoaned Franco’s “insufficient appreciation of the free economy,” calling him “rightist in politics” but “leftist in economics.” But NR happily touted Spain’s economic liberalization and modernization—led by the Catholic conservative lay group Opus Dei—as its economy boomed in the 1960s, only passingly worrying about the “subtle danger” of economic growth to the Spanish soul.

Likewise conservatives downplayed Franco’s repression and the possibility of Spanish democracy. Kuehnelt-Leddihn repeatedly highlighted Spain’s relative freedom. “Franco, personally a pious man, conducted a dictatorship under which anything was possible—short of anti-Catholicism.” Kuehnelt-Leddihn also praised Franco for emancipating women and allowing the masses to achieve “a modicum of well-being.” On the contrary, as historians have documented, Franco’s Nationalists considerably reversed women’s rights and violently reasserted the viciously unequal oligarchy of pre-Republican Spain. Ultimately, tourism and aid money lifted landless farmers out of poverty under Franco, but that disruption to the ancien economic régime was hardly intentional.

“The next step, more freedom of expression, will come unless the organized Left makes a last, desperate attempt to unbalance the liberalizing process,” remarked the aristocratic Kuehnelt-Leddihn. Anti-democratic fears and monarchist sympathies ran through conservatives’ analysis of Spain from the mid-1950s through the mid-1970s. “Would ‘free elections’ truly benefit the cause of liberty? Or would they set the country back—back to 1936?” Kuehnelt-Leddihn asked rhetorically. In the traditionalist journal Modern Age, Francis Wilson claimed, “It seems impossible to introduce the more extreme form of parliamentary democracy into Spain.” Instead, “Spain is a monarchy.” Another National Review writer concluded that “political freedom, American style, is not, in Spain, compatible with order.” It is “Spain’s authoritarian monarchists who alone can create order in Spain.” In the mid-1970s, Buckley, partly walking back earlier criticism of Franco, claimed to understand the Generalissimo’s reluctance to give up the dictatorship, and praised how his “intuitive grasp of the incompatibility of Spanish culture and John Stuart Mill democracy” had tempered his successors.

What American conservative intellectuals thought they understood was the traditionalist heart of the Spanish character. They applauded it against leftism of all kinds. Reid Buckley described how “781 years of uninterrupted fighting for one’s land and faith does something to a people.” The Spanish became “fierce followers of Christ” with a “racial and religious self-consciousness” forged by Moorish domination. He waxed that “Spain is an idea, a dream and—always—a crusade.”

In Francoist terms, it was a struggle of “Spain” against “Anti-Spain” (language echoed in present-day America by both the Claremont Institute and National Conservatives). In 1961, Lev Lednak acknowledged in National Review that these terms were not conciliatory, and that Francoists overstated the claim all liberals were Reds. But still he concluded the Anti-Spain side destabilized the nation by refusing to accept their defeat. Managing, impressively, to mangle both Spanish and American history, Lednak claimed “It isn’t that the Spanish victors since the Civil War have behaved so differently from the American victors [in the American Civil War], but that the Spanish vanquished have behaved so differently from the Southerners” by not accepting Nationalist victory. In the conservative view, left-wing refusal to pack up and concede all to Franco made democracy untenable in Spain.

National Review and American conservative intellectuals broadly celebrated the Nationalists and sympathetically, if sometimes critically, covered for Franco. They reported Royalist gossip and occasional scoops, including a bizarre claim that President Kennedy met with Spanish dissidents. Conservative sympathy for Francoist Spain was clear not only in how many conservatives lived in or visited Spain, but also in the personnel Buckley published on the subject—like Sir Arnold Lunn, an English fascist sympathizer and Franco supporter who wrote several articles on Spain for the magazine. But as with Hungary and the American right today, for some of these writers Spain offered much more: a chance to reimagine right-wing politics.

Traditionalism, Spanish-style

“The American Right has shown itself alarmingly naïve” of conservatism “outside the Anglo-Saxon diaspora of Western civilization,” noted Detroit native Frederick “Fritz” Wilhelmsen in National Review in 1966. This sentiment is echoed today as traditionalist conservatives, buffeted by changing social mores and laws, look abroad for something more robust than free markets, originalist jurisprudence, and small government.

Like today’s conspicuously Roman Catholic (or Eastern Orthodox, in Dreher’s case) pro-Orbán crowd, what attracted traditionalists to Spain in the 1960s was, above all, religion. Figures like Wilhelmsen, Francis Wilson, and Buckley’s brother-in-law Brent Bozell approved of Spain’s state-backed religiosity. To Bozell, Spain came to represent “an ideal, integral Catholicism”; to Wilhelmsen, a tantalizing glimpse of a “res publica Christiana.”

Catholicism appeared richly embedded in Spain. Francis Wilson, a political scientist at the University of Illinois and convert to the Catholic Church, became fascinated by the “commitments of the Latin mind”—more “profound” and its “conflicts more demanding” than those of Anglo-American conservatives. He admired the rightist thinker Ramiro di Maeztu, co-founder of the far-right monarchist journal Acción Española and theorist of Hispanidad, the belief that Catholicism and the Spanish language were the core of a “colonizing achievement” of historical proportions. Wilson hoped to blend the thick commitments of the Spanish right with the best elements of Anglo-American conservatism.

More romantic than Wilson, Wilhelmsen became enamored of Carlism, what he called “the most purely lyrical and militant response to Liberalism that has come out of Catholic Europe.” Carlism began as a dynastic dispute among Spain’s monarchs in the 1830s, but became intertwined with ultratraditionalist politics. Under the slogan “Dios, Patria, Fueros, Rey,” Carlism was a latent, alternative right to the oligarchic constitutional monarchy. It seemed to have slipped into terminal decline during the early twentieth century before the anti-clericalism of the Spanish Republic revivified it. Tens of thousands of men joined its red-bereted militia, the Requeté, especially in northeastern Spain, and received training from Fascist Italy and fought as Nationalist shock troops. The anti-modernist Wilhelmsen took a summer professorship in Pamplona, the heart of Carlist country, and embraced “the permanent protest to the Revolution.”

Likewise, the politics of Bozell, who was also a convert to Catholicism, transformed in Spain from run-of-the-mill, if hardline, Republican conservatism into something far more mystical. Living by El Escorial, the palace-monastery symbolic of Spanish imperial grandeur, informed Bozell’s vision of a magnified Christian West. Returning stateside to speak at a Young Americans for Freedom rally at Madison Square Garden in March 1962, Bozell gave a stirring—and esoteric—address on Western Civilization to 18,000 conservative youth. He began by proclaiming, “We of the Christian West owe our identity to the central fact of history—the entry of God onto the human stage” and concluded with an unequivocal defense of colonialism and a call to cleanse the West of secularizing elements and a roll back communism.

Back in Spain two months later, Wilhelmsen took Bozell and his family to an enormous Carlist celebration in Montejurra—the site of a historic battle. Bozell’s biographer, quoting Bozell’s wife, notes that “this kind of thing—simple peasants with improvised weapons defending their religion and their way of life—‘always got Brent and Fritz going.’” At the celebration, the Requeté’s national secretary celebrated the crusading ideals of the Nationalist alliance between Carlism, the Falange, and Franco’s army.

Finally, in September, Bozell took part in a foundational debate over the nature of conservatism. Sounding like today’s Hungary fans, Bozell doubted whether a libertarian right could be “responsive to the root causes of Western disintegration.” At best, freedom was a secondary principle to something greater.

Bozell dismissed libertarian claims that virtuous acts only counted if they were freely chosen. To demonstrate, he contrasted American and Spanish divorce laws, sarcastically suggesting that Spain’s traditions interfered with freedom, but that American divorce laws should also be made freer, the stigma removed and divorces financially subsidized to maximize moral heroism. Instead, Bozell wanted to “establish temporal conditions conducive to human virtue—that is, to build a Christian civilization.” This meant families, schools, and the government were subject to a public orthodoxy patterned on a transcendent order.

At the time, Bozell’s long essay seemed to some seemed like a possible framework for intellectual conservatism. It became very much a minority report. Bozell rightly perceived modern conservatism “invariably consists in borrowing from the libertarians their principles and programs, and from the traditionalists the divine imprimatur.”

Against this tendency, he and Wilhelmsen founded a traditionalist Catholic journal, Triumph. They began hosting a summer school in Spain for American students “bored with Western education,” and founded a small youth movement—the Sons of Thunder—who wore Carlist uniforms and protested abortion clinics.

Bozell’s pronouncements became increasingly radical. American conservatism had failed with Goldwater in 1964, he charged. Conservatism and liberalism were fundamentally the same, and politics would not survive the death of God. Hence, Bozell predicted, conservatives would “swell the ranks of a proto-fascist reaction to the collapse of secular liberalism.” Bozell even rejected his earlier view the West was a Christian society. He prayed instead for a “Politics of the Poor,” combining economic redistribution with Christian cultural orthodoxy, cautioning there were “no short cuts to making a new Christendom.”

Admittedly “a poor politician,” Bozell alienated friends and allies, becoming estranged from the American right as his health failed. He faded into relative obscurity. (One of his sons, L. Brent Bozell III, hewed closer to the conservative mainstream as a Conservatism, Inc. career apparatchik. His son, in turn, Brent Bozell IV, has been charged for his involvement in January 6.)

The Temptation of Strongmen

Franco’s conservative defenders fell prey to many myths. He was repressive; Spain successfully democratized after his death, while the institutional prestige of the Church collapsed. The Spanish Republic had been anti-clerical, but the government sought to moderate against opposition and prevent anti-clerical violence. Instead, the catastrophist right instigated violence to destabilize the Republic. Franco’s conduct in Spain’s Civil War, which began as a right-wing coup, was not heroic but brutal and methodical and supported by Mussolini and Hitler. They overstated the crimes of the Republicans, and buried the far greater crimes of the Nationalists, and misunderstood the role of the Soviet Union.

The fact that American conservatives were willing to overlook all this in a sympathetic strongman should give today’s Hungary enthusiasts pause.

The parallels are inexact, of course. Franco was a twentieth-century dictator, Orbán is a twenty-first, with all that entails. The Cold War-footing of the 1960s distorted judgement. Notwithstanding what talk radio might say, Spanish communism and modern progressivism are not the same. Yet the right-wing—and especially traditionalist—temptation toward dictatorship remains.

Deep down, Rod Dreher knows the answer to the question he poses—what is the cost of using politics as a bulwark? As he put it in response to his Catholic integralist critics, “If outward obedience to the law was sufficient to guarantee a Christian society, Spanish Catholicism wouldn’t have collapsed shortly after Franco died in 1975.”

Traditionalism is the most fantastical of right-wing outlooks. How can one force an imagined past into reality? Spain—and conservative enthusiasm for it—teaches that state-imposed traditionalism is a mirage. It is at best utopian, and more likely, repressive and self-defeating. Today’s admirers of Orbán’s Hungary should take note.