Love and Libertinism: The Endless Fascination of ‘Dangerous Liaisons’

Written in 1782, the scandalous, repeatedly banned novel lives on, generating ever-new adaptations—and an infinite variety of readings.

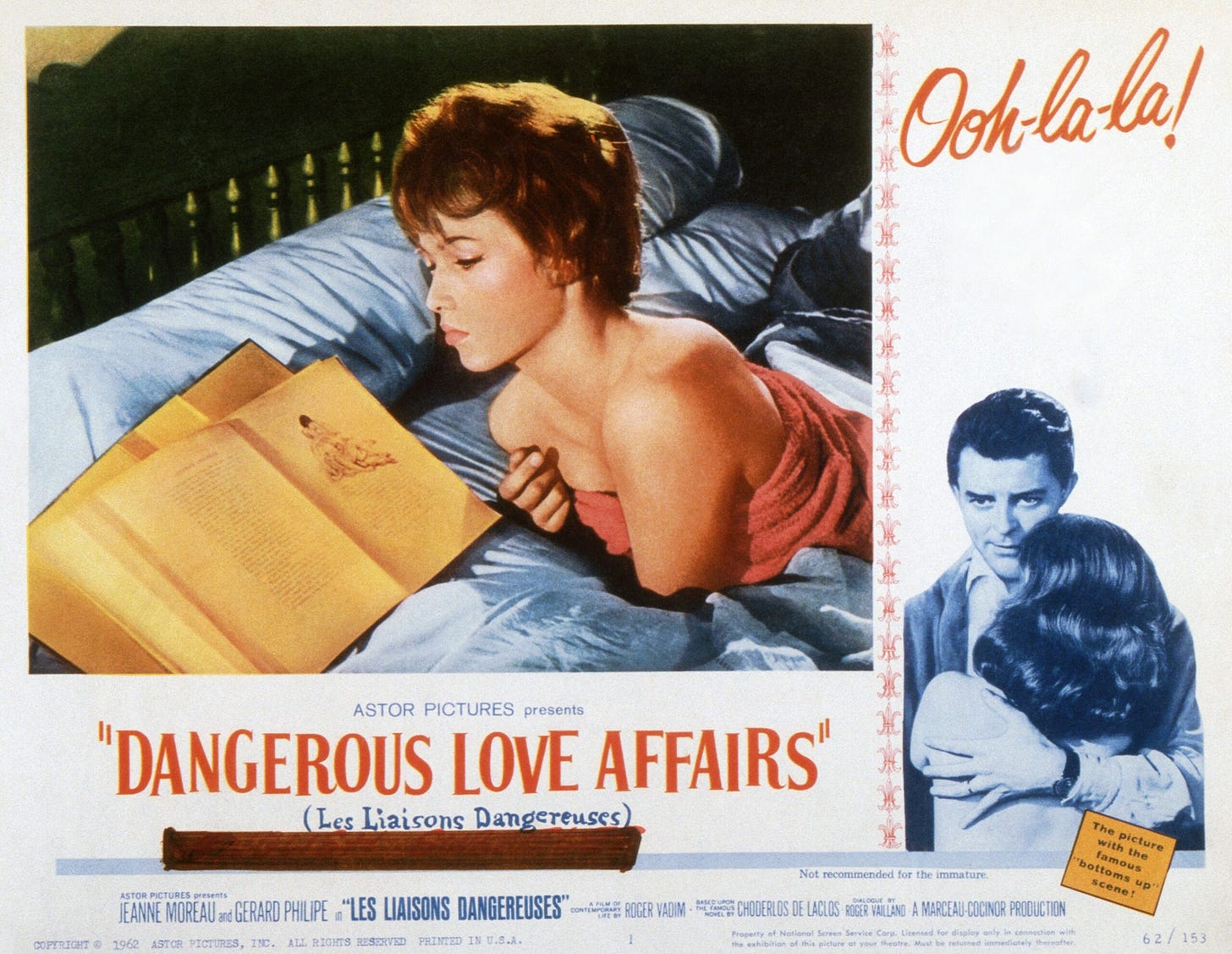

THE EIGHT-EPISODE MINISERIES Dangerous Liaisons, which ran in November and December on the STARZ cable channel and was billed as a “prequel” to the original 1782 novel and the renowned 1988 film, was—remarkably—the second new Liaisons adaptation to appear on the small screen in the last year. (The first one, a French film that came to Netflix in July, reincarnated the eighteenth-century aristocrats as modern-day high-school-age Instagram influencers.) And these are just the latest entries in a long list of the novel’s retellings and reimaginings over the past 40 years. The Oscar-winning Stephen Frears film, based on Christopher Hampton’s 1985 hit play Les Liaisons Dangereuses, was followed by several other screen and stage versions as well as an opera, at least four musicals, and a ballet. For an almost quarter-millennium-old book written in a practically extinct epistolary genre and set in a world that ceased to exist less than a decade after its publication, Les Liaisons Dangereuses has astonishing vitality.

The secret of its appeal is a much-discussed subject. The most common explanation is that Les Liaisons Dangereuses offers an unflinching, timelessly incisive look at the sexual battlefield and its vagaries of love, hate, desire, and deceit—as well as an irresistible opportunity to get inside the heads of two depraved but dazzling protagonists. Yet the multitudes of readers, critics, and scholars who have been fascinated by Choderlos de Laclos’s novel over the years have seen radically different things in it: from social critique to transgressive cynicism, from the triumph of cold intelligence to the affirmation of love. Few novels, noted French literary scholar Caroline Fischer in a 2003 essay, lend themselves to such a range of often-contradictory interpretations: “The only certainty among critics is that this work is enigmatic, ‘undecidable,’ polyphonic and polysemic.” This multiplicity of readings and meanings, based on the tantalizing ambiguities of the text, is itself a key to the fascination.

Notes on a Scandal

THANKS IN PART to the proliferation of modern adaptations, the basic story of Les Liaisons Dangereuses is by now familiar. The central characters, the vicomte de Valmont and the marquise de Merteuil—wealthy, glamorous, amoral French aristocrats living in the twilight of the ancien régime—are former lovers and secret allies in sexual gamesmanship. In this case, the games begin when Merteuil seeks to recruit Valmont to seduce her teenage cousin Cécile de Volanges as revenge against her fiancé, who once left Merteuil for another woman. (The man is very particular about avoiding cuckoldry, so cuckolding him before the wedding would be, as it were, the cherry on top.) Valmont refuses, both because the seduction of a convent-bred innocent is an insultingly easy task and because he has a more ambitious project: the pious Madame de Tourvel, she of strict morals and wifely devotion. After some verbal jousting during which Valmont tries to coax Merteuil into an infidelity to her insipid boyfriend du jour, the duo makes a deal: if Valmont succeeds with Tourvel, Merteuil will spend a night with him.

At first, the story unfolds as a nasty and cynical but also sparklingly funny comedy of manners and sex. Valmont pursues Tourvel during a summer vacation at his aunt’s château, playing a penitent libertine awakened to true love while indulging in occasional romps with other women—notably a courtesan on whose naked back he writes Tourvel a love letter, one of numerous smutty gags. Merteuil embarks on Plan B for Cécile, encouraging her secret romance with the young chevalier Danceny. (Tourvel’s husband, a président or head of a regional court, and Cécile’s fiancé, the comte de Gercourt, a regimental commander, are both conveniently away on business.)

Of course, it’s all fun and games until someone loses a heart, a life, or, later, an eye. After many twists—which include Valmont having his way with Cécile while ostensibly acting as Danceny’s emissary—comes the tragic denouement. Tourvel yields to Valmont, with whom she is by now passionately in love. Merteuil, stung by Valmont’s apparently genuine feelings for his conquest, goads him into brutally discarding Tourvel, then reneges on their agreement by rejecting him; she adds insult to injury by taking up with Danceny. The libertines’ partnership dissolves into war, and Valmont is killed in a Merteuil-engineered duel with Danceny mere hours before a shattered Tourvel dies in a convent. Merteuil is ruined in multiple ways after Danceny publicizes her scandalous letters—a poisonous gift to him from the dying vicomte—and flees France; a bitter Danceny goes away to join the quasi-monastic Knights of Malta, and Cécile takes the veil. (Those last details are omitted from the Frears film.)

But those are the bare facts; what really happens is profoundly ambiguous. Does Valmont “really” come to love the virtuous Tourvel, or does he always see her as his “project”? Does Merteuil love Valmont, or only want to win their battle of wills? Does she seek his death in provoking his duel with Danceny? Does he seek death? The list could go on and on.

The inherent, Rashomon-like subjectivity of the epistolary format is compounded by the fact that, more often than not, words can’t be trusted. When Merteuil writes wistfully to Valmont, “In the days when we loved each other, for I do believe it was love, I was happy; and you, vicomte…?”, is it a sincere emotion, or well-placed bait, or both? Even Valmont’s apparent cri de coeur to Danceny while lamenting Tourvel’s loss, often regarded as the novel’s key line—“Believe me, there is no happiness except in love!”—is interpretable as a tactical move to coax Danceny away from Merteuil and back to his earlier love, Cécile.

Add self-deception to deception, and things grow even more complicated. For instance, if Valmont is some sense in love with Tourvel all along—and the text can certainly support that reading—then his declarations of love are a hopelessly tangled web of truths and lies, and even the letter written on the courtesan’s back is ultimately a joke on Valmont himself.

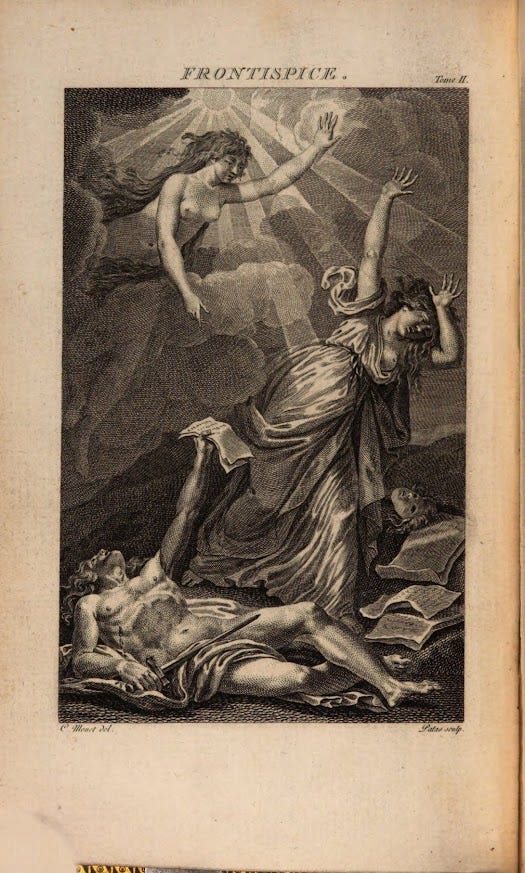

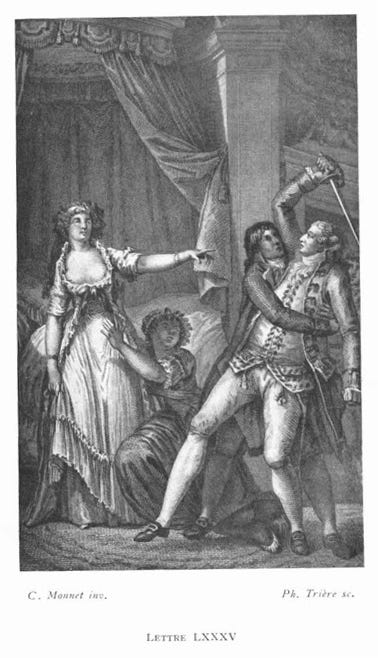

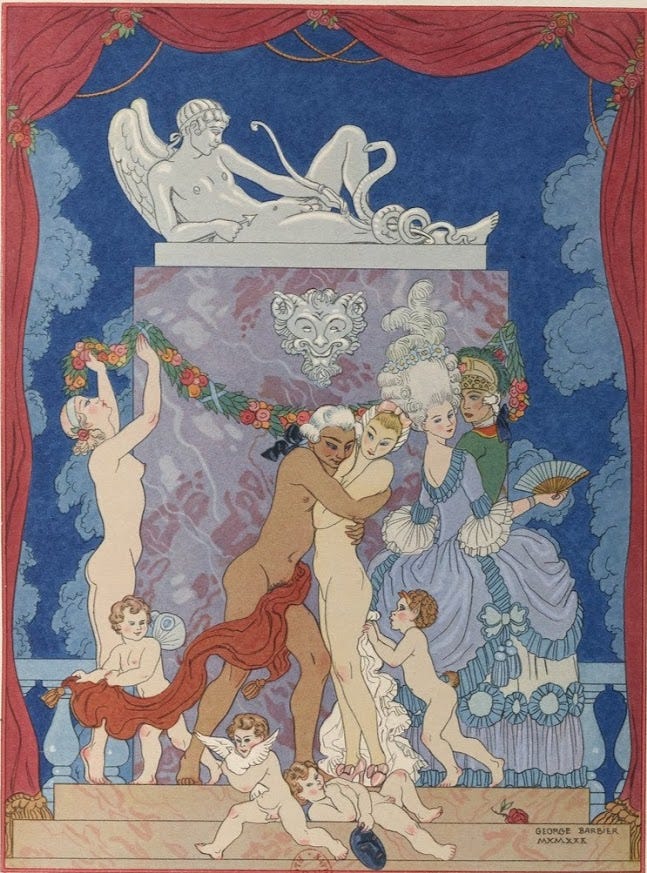

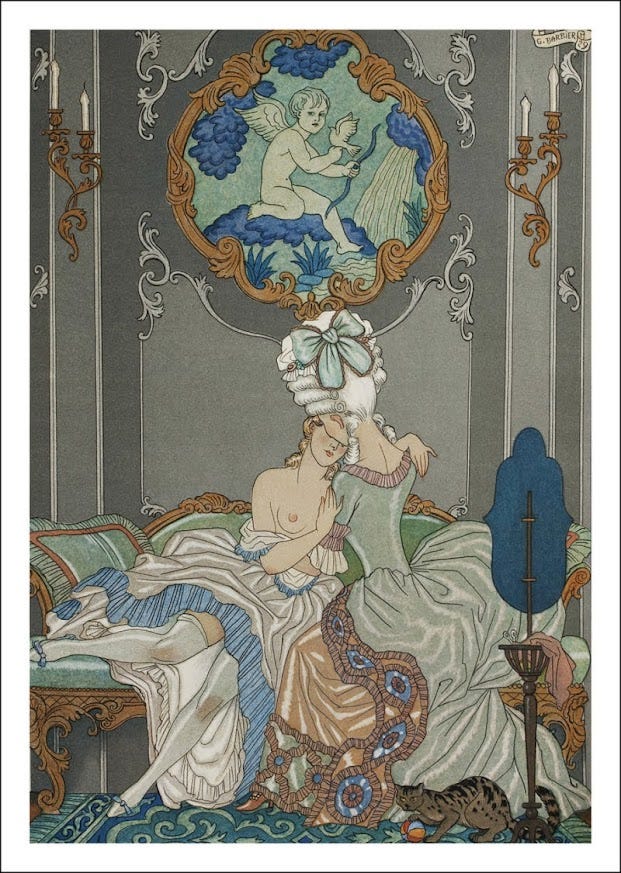

The unanswered questions extend to the whole of the novel. Is Les Liaisons Dangereuses a work of icy intellect, or of hot passion beneath the cerebral surface? A moral tale in which libertinism is exposed and condemned, as Laclos claimed—or a “diabolical” book that makes sin so fascinating that its wages are easily forgotten? (In the nineteenth century, the novel was repeatedly banned for obscenity, despite the lack of almost any explicit content; while its pornographic reputation was due partly to racy illustrations, it was also a matter of both perceived immorality and its power of imaginative insinuation.) A feminist work that critiques women’s oppression and offers a brilliant female protagonist in rebellion against male dominance, or a misogynistic tract in which a powerful woman is depicted as a “power-hungry, castrating female” and accorded far less sympathy than the male sexual predator?

The mystery is heightened by the enigmatic figure of the author, Pierre-Ambroise-François Choderlos de Laclos, an artillery officer and engineer for whom writing was a side hobby. Before Les Liaisons Dangereuses, Laclos, the son of a recently ennobled government official, had published some minor poetry and penned a libretto for an unsuccessful opera; after it, he drafted three unfinished essays on women’s education, unpublished until the twentieth century. He was also a pamphletist during the French Revolution, when he served as personal secretary to the liberal Duc d’Orléans. Having narrowly survived the Reign of Terror, Laclos later became a general in Napoleon’s army and contributed to some important innovations in artillery before dying of malaria in Italy in 1803, aged 62.

Les Liaisons Dangereuses, an instant and scandalous bestseller, made Laclos not only famous but infamous; some even suspected him of being the anonymous author of the Marquis de Sade’s grotesquely pornographic Justine. This sulphurous reputation also played into a loopy conspiracy theory—concocted in 1796 by a royalist journalist and eventually recycled by twentieth-century reactionaries—in which Laclos, supposedly a “monster of immorality” like his creations, was the evil genius of an Orléanist/Masonic plot behind the French Revolution. But the real Laclos was no Valmont-like immoralist: While he did have an illegitimate child in 1784, he promptly married the mother, Marie-Soulange Duperré, and was a faithful, loving husband and devoted father. Late in life, he contemplated a second novel, intended to convey “the verity that there is no happiness except in family life”; perhaps luckily for his literary legacy, he never got around to writing it.

Ambiguous Libertines

IT’S QUITE TRUE that Laclos’s charismatic libertines—sometimes known as “the infernal couple”—are as alluring as they are appalling. Their letters seduce us with their ironic intelligence and verbal virtuosity, their protean mimicry, their cynically astute observations on human behavior and equally cynical wit. (Valmont, after dictating Cécile’s latest letter to her unsuspecting would-be lover: “The things I do for this Danceny! I have now been his friend, his confidant, his rival, and his mistress!” Merteuil, after Valmont refrains from taking advantage of Tourvel’s moment of weakness only to be stunned by her departure from the château the next morning: “What do you expect a poor woman to do when she gives herself and the man doesn’t take her?”) We half-admire the brilliance of their human puppeteering, however malign. (Merteuil, a master of gaslighting over a decade before the gaslight was invented, not only persuades a distraught Cécile to see her deflowerment—a “seduction” somewhere between coercive manipulation and rape—as a welcome initiation into the joys of sex, but makes her apologize to Valmont for locking him out the next night.) We’re lured into enjoying the dark comedy of their twisted schemes—as when Valmont gets around Tourvel’s refusal to see him by persuading her confessor that he wants to return her letters and make amends before devoting himself to God—and even rooting for those schemes to work.

There is no question that Valmont and Merteuil are much smarter, funnier, more dynamic, and more interesting than the people they treat as dupes and playthings to their almost godlike powers. (“Fools walk this earth to keep us entertained,” observes Merteuil, quoting a comedy verse.) Their flouting of social and moral norms, moreover, is attenuated by the book’s unsparing critique of these norms: Conventional morality is exemplified by Cécile’s mother, Madame de Volanges, who congratulates herself on securing her daughter’s “advantageous marriage” to a much older stranger and fulminates against Valmont’s iniquities but still receives him in her circle, shrugging it off as one of society’s “inconsistencies.” Most people mindlessly obey the rules; Valmont and Merteuil—especially Merteuil—make their own.

And yet the idea that Les Liaisons Dangereuses is a thinly veiled glorification of libertinism can only be based on a superficial reading—almost as superficial as the pretend moralism of Laclos’s tongue-in-cheek “Editor’s Preface,” which praises the book as a useful lesson on the perils of friendships with immoral people.

For one thing, if Laclos gives his libertine protagonists a glamorous mystique, he also repeatedly demystifies them. This is especially true of Valmont, who fancies himself a proto-Nietzschean Übermensch of sorts—fully in control of himself and never at the mercy of fate like mere mortals—but is in fact easily manipulated by his partner in crime and ruled by his passions in ways he rarely admits. For all his charm, he can be ridiculously smug and vain, a man who deftly plays on others’ weaknesses but is clueless about his own. Valmont is further deflated by constant needling from the marquise, who even suggests that some of his vaunted conquests are fictitious. On the flip side, more sympathetic moments in which he shows a capacity to be genuinely moved—not only by Tourvel, but by the needy villagers he helps as a stunt to impress her—further undercut his pretensions to be above sentiment.

Merteuil, who is not only a libertine but a liberated woman, is in a very different position than Valmont and far more impressive; but her quasi-heroic aura, too, sometimes slips to reveal petty and pointless cruelty, and her game also spins out of control with disastrous results. What’s more, Les Liaisons Dangereuses leaves little doubt that in the end, the libertine “system” that treats love as an illusion and sex as a battlefield is deeply unsatisfying to its true believers. Valmont is surprisingly explicit about it in an early letter to Merteuil:

Let’s be honest: in our affairs, as cold as they are easy, what we call happiness is hardly even pleasure. Shall I tell you? I thought my heart had withered away, and with nothing left but the senses, I complained of a premature old age. Madame de Tourvel has given me back the enchanting illusions of youth.

Merteuil repeatedly mocks and chides Valmont for lapsing from his libertine “principles,” and yet her own are hedged with paradox. One of the novel’s standout passages is her mini-essay in Letter 131 reflecting that unless there is love at least on one side, pleasure quickly turns to revulsion. Later, as her conflict with Valmont escalates, her last full-length letter to him throws back in his face the same libertine code she had earlier claimed to enforce: “Isn’t one woman worth another? Those are your principles.” Both halves of the “infernal couple” may forswear love as a weakness, but they still crave it from others: Valmont from Tourvel, Merteuil from Valmont and from 20-year-old Danceny, whose appeal is that he will love her “as one loves at his age.”

Bourgeois Morality and Its Discontents

IF LES LIAISONS DANGEREUSES IS NOT an ode to libertinism, it is even less a victory of good over evil. Even the punishment of the wicked retains gray areas. Valmont’s end, many critics have argued, looks less like just deserts than an honorable, even heroic death. Merteuil’s comeuppance seems so extreme—social disgrace, loss of fortune to a lawsuit, loss of looks (and one eye) to a deus ex machina illness—that it’s widely regarded as contrived or even deliberately false, an ironic nod to moralism. But as usual with Laclos, things are not what they seem. The marquise’s financial ruin is mitigated by her flight to Holland—then a locus of intellectual and personal freedom—with a stash of jewelry, money, and other valuables. As for disfigurement by smallpox, it is at least worth considering that the news of Merteuil’s disease may be another strategic ploy (a possibility proposed by maverick scholar Roger Bayard and explored in several derivative fictional works, including Philippa Stockley’s well-received 2005 novel A Factory of Cunning). Laclos plotted his novel with an engineer’s precision, and it cannot be an accident that all the information about the marquise’s ravaged face and lost eye comes via the chronically “blind” Madame de Volanges—who has no knowledge beyond “I’ve been told she is truly hideous.” Obviously, this doesn’t disprove Merteuil’s disfigurement, to which some believe her name contains a coded allusion (mort d’oeuil, “death of the eye”). But it’s sufficiently unproved to leave room for doubt.

In any case, while the wrongdoers suffer, so do the wronged: Tourvel’s breakdown, illness, and death are harrowing; Cécile’s life is over before it has begun. The other “good guys”—Danceny, Madame de Volanges, and Valmont’s aunt Madame de Rosemonde—also face bleak prospects; what’s more, their “goodness” is itself plenty tinted with ambiguity.

The hollowness of Volanges’s social-credit-driven morality becomes fully apparent when her principal reaction to the disgrace of her cousin and friend the marquise is to sigh, “It’s awful to be related to this woman”—and, in her next letter, to stress that she is “a very distant relative.” The idealistic Danceny, ostensibly the novel’s instrument of justice, is self-righteously judgmental toward Cécile’s infidelity despite his own role in her ruin and his own affair with Merteuil. (He may also be a murderer: The account of Valmont’s death mentions “two stab wounds to the body,” suggesting a deliberate strike at a wounded opponent.)

The venerable Rosemonde, often regarded as the book’s moral center—at its conclusion, she is effectively given the dual role of arbiter/archivist as the depositary of nearly all the letters—has even more shades of gray. There’s a strong case, as Caroline Fischer demonstrates in the essay quoted earlier, that Valmont’s doting aunt more or less knowingly facilitates his seduction of Madame de Tourvel despite being fairly well aware of his character. And at the end, her benign wisdom may well mask a concern with protecting her nephew’s memory and her family’s good name above all, while shifting all the blame to the disgraced marquise, keeping Madame de Volanges in the dark about what happened to her daughter, and treating Cécile as unavoidable collateral damage.

A Triumph of Love—or a Victory Over It

IF GOOD DOES NOT WIN, is there in Les Liaisons Dangereuses, as some literary critics have claimed, a “triumph of love”? At first glance the idea may seem absurd, considering how its relationships not only end but begin and unfold. Valmont’s pursuit of Tourvel is a litany of reprehensible acts, from minor manipulations to spying and mail theft, and his anticipation of mutual pleasures alternates with creepy fantasies of making Tourvel’s virtue “expire in a slow agony.” The presence of sincere feeling even early on—for instance, in his rapturous paean to Tourvel in rejoinder to Merteuil’s putdowns—does not make this pursuit less disturbing; neither does the fact that his tactics work only because of Tourvel’s own feelings. In the end, his winning move is to convince her she must save him from suicide; moreover, his first “possession” of her takes place while she is either in a faint or a self-willed stupor (not surprisingly, its consensualness is hotly contested) and leaves her utterly distraught.

And yet after this, Laclos gives us a passionately lyrical scene that Swiss scholar Anne-Marie Jaton regards as the book’s crucial moment. Pulled out of her despondency when Valmont uses a stock gallant phrase assuring her that she has made him a happy man, Tourvel consciously chooses love and dedicates herself to her lover; there follows, writes Jaton, an “epiphany” in which the libertine and the virtuous woman discover the full integration of love and desire, sensuality and sensibility. In Valmont’s words:

It was with this naïve, or sublime, candor that she abandoned herself and her charms to me and magnified my happiness by sharing it. Intoxication was complete and reciprocal; and, for the first time, mine outlasted the pleasure.

Tourvel’s undoing is matched by that of Valmont, who is shocked when his infatuation with the présidente does not dissipate with her “fall” but instead turns to an overpowering “unfamiliar enchantment.”

It cannot end well, of course. While Tourvel basks in her bliss and in Valmont’s tenderness, Valmont, whose ego balks at being “mastered” by an uncontrollable feeling, keeps trying to prove to himself and to Merteuil that he’s not in love: “It’s hardly my fault if circumstances compel me to play to the part.” Merteuil will remember these words when she composes for him, under the transparent guise of a story about a “friend,” a brilliantly ghastly breakup letter that starts with, “One gets bored with everything, my angel; it is a law of nature. It’s not my fault,” and continues with the same relentless refrain. Valmont promptly sends a copy of the ghostwritten note to Tourvel. Allowing for the usual ambiguities, it seems likely that he never really means to drop the présidente but only to show that he can—and is too caught up in his game with the marquise to consider the potential fallout. His subsequent reports to Merteuil convey a gradual shift from glib self-assurance to growing anxiety as he glimpses that he’s done something irreparable; his later attempts to repair it will come to naught.

So is it true love or a “project”? A narcissist’s thrill at Tourvel’s adoring devotion, followed by equally narcissistic vexation at having broken a favorite toy? Is Valmont still playing a role when he writes to Danceny two days before his (and Tourvel’s) death, “I would give half my life for the happiness of devoting the other half to her”—or do those words not only express real pain and longing, but finally confirm Valmont’s transcendence of his habitual narcissism? Most readers, critics, and adapters of the novel opt for the poignant second version over the nihilistic first. (Not that the poignancy ever lapses into sentimentalism: The last thing Valmont will ever write is a supremely catty missive to Merteuil gloating about his success in getting Danceny to ditch her for Cécile.)

Another piece of evidence is a letter that, strictly speaking, isn’t in the novel: Valmont’s futile plea to Madame de Volanges to convey his love and contrition to the extremely ill Tourvel. That letter was removed by Laclos from the final copy, leaving only a snippy mention from Volanges questioning Valmont’s sincerity and an “editor’s note” saying that the letter was omitted since this question could not be resolved. But, in typical Laclos manner, the note is an ironic inversion of the truth: As Oxford University professor and leading Laclos scholar Catriona Seth says in the 2021 French TV documentary Les liaisons scandaleuses, the author likely cut Valmont’s letter precisely because “it gives away too much.” That reading too is open to debate; even so, there is something very raw and real about the letter’s frantic desperation, its brusque language shorn of courteous phrases, and its blunt admission of “dreadful wrongs” (a counterpoint to the earlier refrain of “It’s not my fault”). Of course, whether this letter, not printed in Laclos’s lifetime but included as an appendix in most modern editions, exists or doesn’t exist in the canon text is itself a very Laclosian paradox: It’s Schrödinger’s letter. For that matter, the Valmont/Tourvel storyline is Schrödinger’s romance: In the novel, unlike the 1988 film, we never know whether Valmont speaks of Tourvel in his final moments, or whether his death is, in effect, suicide by Danceny.

A Revolutionary Woman

THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN Valmont and Merteuil, whom many regard as the novel’s “real” couple, is even more of a mystery. We know they are ex-lovers who parted by mutual accord, a parting that Valmont at times clearly regrets; we know both are jealous of each other; whether there is love on either side is a question that has a thousand answers. And yet what makes the duo so riveting is not the potential romance from hell but the alliance that has undercurrents of tension and rivalry long before it turns to open warfare. For all the talk of “total trust,” their pact, we eventually learn, is based on mutually assured destruction: He can nuke her reputation with her letters, she is privy to a presumably political “secret” that could send him to prison or exile. And yet theirs is also a real bond, one that goes beyond its practical purposes. For one thing, Valmont and Merteuil are each other’s audience—a particularly important function for the marquise, who cannot parade her exploits in public. They are also, in each other’s eyes, a secret society of equals—“I’m tempted to believe there’s no one in the world worth anything except you and me,” writes Valmont—even if one of them is, to paraphrase Orwell, clearly more equal than the other.

Merteuil’s dominant status in the Valmont/Merteuil partnership is just one of the things that make the marquise a truly revolutionary figure in literature. The male libertine has a long literary pedigree; Valmont is in some ways a direct descendant of Lovelace in Samuel Richardson’s 1748 Clarissa (referenced twice in Laclos’s novel). Pleasure-seeking women were certainly not new to eighteenth-century literature, but they always appeared in relation to male characters as lovers, mentors, or corruptors. Merteuil as a female libertine protagonist with full agency and autonomy—“Lovelace en femme,” as contemporary critic Melchior Grimm put it—has no antecedents.

Merteuil’s autobiography and quasi-feminist manifesto—Letter 81, positioned almost exactly at the novel’s midpoint—can be described as the centerpiece of Les Liaisons Dangereuses, and is certainly its most extraordinary part. It includes some memorable vignettes, as when the still-unmarried, sexually ignorant future marquise tries to enlighten herself by telling her confessor she has done “everything women do”; she learns no details, but the priest’s horrified reaction convinces her it’s got to be good. Above all, though, it is a hymn to the sovereign self-made individual: “I could say that I am my own creation,” declares Merteuil. The outward facts of her story, from sheltered girl to teen bride to young widow, are quite ordinary; but, armed with a remarkable mind and an indomitable will, she has crafted for herself a life that can maximize her freedom and her pleasures. All it takes is steely self-discipline and the well-honed skill of an actor, with equal skill at writing her own scripts.

Acutely aware of the double standard that makes sexual adventure a “very unequal combat” or a rigged game, Merteuil has not only created her own hedonistic philosophy but fine-tuned a system to protect herself; it comes down to leaving no evidence and ensuring her lovers’ discretion by carrot or stick.

One might argue that Merteuil’s mask of impeccable virtue—prettied up with enough sentiment and flirtation to keep men interested—is unnecessary: While sexual norms in eighteenth-century aristocratic culture were far more restrictive for women than for men, they were still relatively laissez-faire within certain bounds of decorum. Even being “ruined” was relative: A titled lady’s reputation, one such lady reportedly observed, could “grow back like hair.” But Merteuil-style libertine derring-do goes considerably beyond the limits of this tolerance; a respectable façade is a perfect cover that also lets the marquise enjoy the added thrill of deception.

When Merteuil describes herself to Valmont as “born to subjugate your sex and avenge mine,” it’s easy to see this as flagrant hypocrisy given her treatment of the female victims of her schemes. Tourvel aside, she is shockingly callous to Cécile, especially once she decides the girl is too stupid to be a disciple in intrigue. Nor does she hesitate to weaponize the double standards she ostensibly denounces: When Valmont reports an amusing adventure with a former mistress under the noses of her husband and her current lover, Merteuil urges him to feed it to the gossip mill because of a petty grudge against the woman. Yet it would be a mistake to see her as a female misogynist who wants to be an honorary man: It’s more that her feminism is strictly about liberation for one. It still remains, ten years before Mary Wollstonecraft’s A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, a startling and powerfully articulated female rebellion.

Notably, Merteuil pens her manifesto at the point when the always-simmering conflict between her and Valmont has first come to a boil, and while she plans an explicit counterstrike against male tyranny: a far-from-gratuitous subplot involving Valmont’s libertine rival Prévan. Overhearing Prévan accept a challenge to seduce the invincible Madame de Merteuil, Valmont promptly warns the marquise—and is shocked when she gleefully signals her intent to play along. Stung by his condescending worries, Merteuil unleashes a tirade that clobbers the normally loquacious Valmont into nearly two weeks of silence:

How pitiful your fears are! How they prove my superiority over you! . . . Oh my poor Valmont, what a distance there still is between you and me! No, not even all the arrogance of your sex would be enough to fill the gap that separates us. Because you couldn’t carry out my projects, you find them impossible! . . . And what have you done that I haven’t surpassed a thousand times?

Having explained her “system,” Merteuil insists that she didn’t come this far only to run from Prévan. “Conquer or perish,” she concludes in a Game of Thrones-like flourish: “I want him, and I’ll have him; he wants to tell, and he won’t.” And conquer she does: After discreetly inviting Prévan to sneak into her bedroom after a soirée at her house, Merteuil enjoys a lengthy tryst while cleverly ensuring he stays dressed; she then abruptly rings her bell, shouts for help, and tells her servants to eject the intruder. It’s now the man’s turn to be disgraced by the scandal and banished from society. (Interestingly, Laclos preempts all sympathy for Prévan—effectively, a man falsely accused of attempted rape—by recounting his earlier adventure with a trio of women whom he sets up for such a public humiliation that one self-exiles to a convent and the other two to their estates.) When Valmont finally writes to Merteuil—after waiting until he’s scored his own “victory” with Cécile—his grudging compliments suggest not just pique but unease at realizing how thoroughly a man in this career can be beaten at his own game.

Ultimately, of course, Merteuil herself is beaten—as French scholar Collete Cazenobe points out, she doesn’t conquer or perish—and beaten because of Valmont. Is the vicomte her one vulnerability? She says as much in her autobiographical letter: Her longing to “measure swords” with him marked “the only time an attraction gained sway over me for a moment.” We can’t be sure if she means it or is doling out a bit of honey after all the vinegar. Still, at the very least she wants Valmont to love her: Even the breakup letter she ghostwrites for him to send to Tourvel includes the declaration that “a woman I passionately love asks me to give you up.” Whatever the true reason for her rage at him at the end (Is it that he still loves Tourvel? That he’ll always sacrifice love to vanity? That he’s no longer the nonchalant, charming Valmont she loved?) and whatever her intent in provoking the duel, those emotions are undeniably her downfall. But in the context of the novel, this is not a woman’s weakness but a human one: Both Valmont and Merteuil are undone by rationalist hubris, by overestimating the ability of intellect and will to rule the heart and control events.

Les Liaisons de #MeToo

WHEN LES LIAISONS DANGEREUSES WAS FIRST published, the proto-feminist writer Marie de Riccoboni complained bitterly to Laclos that the character of Merteuil was a slander on French womanhood. Later critics saw her as diabolical and unwomanly (“The woman who would always play the man, a sign of great depravity,” wrote Charles Baudelaire in his notes on the novel in the late nineteenth century). That view shifted with the winds of feminism. By the mid-1960s, a major French critical study of Les Liaisons Dangereuses hailed Merteuil as Laclos’s truly great and haunting creation; today, she is often admired as a “feminist icon.” Yet there is also a view—expressed, among others, by University of Leeds professor emeritus David Coward in his introduction to the 1995 Oxford World Classics edition of the book—that Laclos’s own treatment of Merteuil is more antifeminist than feminist: Valmont gets a clean, quasi-redemptive death, while the marquise, defeated by a last-minute reassertion of male solidarity, is “punished comprehensively, even vindictively.” But one can just as easily argue that Merteuil’s exile—with money and possibly, as noted above, even with her looks intact—is by far the better lot, and that her unflinching demeanor before the jeering mob at the Opera has no less dignity than Valmont’s dying reconciliation with Danceny. Notably, too, her public shaming is paired with the triumph of the exonerated Prévan, who gets a hero’s welcome—which does less to restore the “patriarchal order,” as Coward suggests, than to drain moral legitimacy from Merteuil’s condemnation.

Laclos, who would denounce women’s “servitude” and call for a “revolution” in their status in his writings on female education—and who admired Rousseau but pointedly dissented from the latter’s endorsement of patriarchy—may not have been a feminist in the modern sense, whatever that is; the book’s ultimate “message” about male/female relations is as open-ended as much else. (It’s not at all clear, for instance, that one of its famous maxims—Madame de Rosemonde’s “Man delights in the happiness he feels, woman in the happiness she gives”—reflects Laclos’s own view.) But the novel’s sympathy with women is unmistakable, and it has a uniquely rich gallery of fully realized, three-dimensional female characters.

Madame de Tourvel, often treated as a pallid “nice girl” to the charismatic villains, is no plaster saint but a flawed woman with her own fascinating layers of conflicts and lies. She claims to have no vanity but certainly has the vanity of virtue; her confidence in her ability to keep unwanted feelings at bay has parallels to the libertines’ hubris. She deceives herself and others about her marital happiness: “I’m happy, as I must be,” she tells Valmont, thinking to explain how her duty and happiness coincide but inadvertently letting on much more. She heatedly defends Valmont to the censorious Madame de Volanges while professing sisterly affection and pious desire to reform a notorious profligate, yet later keeps silent about his declaration of not-at-all-brotherly feelings. Is she too proud to admit that she was wrong to vouch for Valmont’s irreproachable conduct—or already protecting their intimate conversations from prying eyes?

As Tourvel’s feelings for Valmont grow, her letters shift in tone, from offended and defensive (but full of revealing slips) to tender and pleading, until at last, having nearly succumbed, she flees to Paris and pours out her heart to Madame de Rosemonde. Tourvel’s anguished letter when she thinks Valmont has found religion and stopped loving her—news which she knows she should applaud but which leaves her crushed, humiliated, even angry at God—is a psychological tour de force. Her subsequent declaration to her elderly friend that she has made Valmont the “possessor” of her existence may evoke feminine submission; but it’s worth noting that she expects reciprocal devotion, and her quietly dignified “I neither boast nor accuse myself; I simply say what is” has its own radical courage. The présidente’s blossoming into a passionate woman—one who, unlike many virtuous heroines of the period, such as Rousseau’s Julie in The New Héloïse, is not only loving but fully sexual—is both beautiful and painfully sad in its doomed bubble of illusion, making her eventual fate all the more heartbreaking.

Cécile de Volanges, while often a comical figure, is tragic in her own way: an adolescent who starts out as naïve but also quickwitted and curious, who falls childishly but genuinely in love—and ends up in the clutches of two depraved adults who use and abuse her for fun and vengeance. Her sexual discovery becomes the opposite of liberation, turning her into what Merteuil contemptuously calls a “pleasure machine”; her understanding of the adult world is warped rather than expanded by the libertine duo’s mind games, and her blind reliance on Merteuil stunts her own judgment. In the last third of the novel, she literally loses her voice: Her last three letters are all dictated by Valmont. After she realizes the marquise’s duplicity—and, presumably, the fact that she’s lost Danceny—her decision to take refuge in a convent is almost certainly less about faith than safety in regression to childhood. While Les Liaisons Dangereuses is never didactic, Cécile’s fate can certainly be seen as Laclos’s commentary on the miseducation of girls in the upper-class society of his time.

The question of feminism in Liaisons also inevitably brings up, in recent years, the nexus of issues we now associate with #MeToo: sexual violence and consent. In France, where the novel is a part of the high school literature curriculum, some feminist academics have argued that discussing these questions in class is essential and will make the reading more relevant. Yet attempts at such discussions invite the perils of “presentism.”

Laclos’s novel, after all, takes place in a world where dominant social codes, fully supported by women, dictate that first-time sex will be nearly always preceded by a show of female resistance, often by fake tears, and sometimes by a fake swoon. (When Merteuil remarks that women love a “vigorous and skillful attack” that “keeps a semblance of violence even in the things we grant willingly,” and thus offers a perfect excuse for surrender, she’s not being a “rape apologist” but expressing, for once, an entirely uncontroversial opinion for her time.) It is also a world where girls are routinely married at thirteen or fourteen—usually to much older men—and however abominable Valmont’s conduct with Cécile, the fact that she’s 15 does not make him, as one 2021 article declared, a “[Jeffrey] Epstein figure.” If we were to judge all the characters by modern standards, Madame de Volanges would be a monster pimping her underage daughter to a rich middle-aged man.

It’s certainly possible to critique the social norms reflected in the novel. But attempts to approach it through the prism of “rape culture” or #MeToo almost invariably end up substituting buzzwords for analysis—and, often, distorting the text. Thus, one 2019 paper accuses Merteuil of “slut-shaming” Cécile, even though the point of Merteuil’s lecture is precisely that there’s nothing to be ashamed of. Another not only argues that Valmont rapes Tourvel in their first encounter (a reading that, at least, can be justified by the text) but bizarrely implies that there’s no evidence at all she desires him—while relegating that evidence to grudging end notes. Such readings also tend to wax prosecutorial: Such narrative complexities as Cécile’s confused account of being both upset and aroused by the things Valmont does to her become grounds to accuse Laclos of trivializing sexual violence.

The point isn’t to exonerate Valmont or Merteuil. (Indeed, reviewers at the time of the book’s original publication had no trouble seeing Cécile as a victim of Valmont’s “abuse,” and the view that she is a rape victim was expressed by some critics long before contemporary feminism.) Rather, the point is that to impose a modern politicized framework on eighteenth-century fiction is 1) to misread it—as you will, for example, if you dismiss as victim-blaming the accurate observation that Tourvel’s rebuffs to Valmont abound in mixed signals; and 2) to make it less relatable, not more. The cultural dissonance highlights the temporal distance. Yet when left in its historical context, Les Liaisons Dangereuses is a startlingly “modern” book in which the setting is extremely different from ours but the psychology never feels alien or incomprehensible.

Legacies of Liaisons

ONE COULD SAY MUCH MORE about the things that make Les Liaisons Dangereuses so remarkable, from the stark individuality of even minor voices (the one letter from Valmont’s valet is a gem in which obsequiousness toward Monsieur is mixed with his own brand of man-of-the-world snobbery) to the pinnacle to which it raises epistolarity. Here, in contrast to Clarissa or Héloïse, the letters are of plausible length, always have a plausible purpose, and exist within the flow of daily life in which people hurry to finish writing by dinner or mail collection, or write long letters on sleepless nights or rainy days; moreover, letters are not just a narrative vehicle, but an essential part of both plot and psychological development. (Merteuil, Valmont, and Tourvel are all destroyed by letters.) One could mention the ways in which eye-opening details can be read (or easily missed) in passing allusions to “off-camera” conversations and incidents. Or the subtle, multiple ways in which the Prévan subplot mirrors the main story; or the ironic and often karmic foreshadowings lurking in plain sight. Merteuil makes casual jibes about how harmless Danceny is, but he will ruin her; an irritated Valmont snaps that his aunt “has nothing left except to die,” but she will outlive and mourn him.

Yet, because of its scandalous nature, this masterpiece remained underappreciated for a long time. Hobbled by obscenity bans for much of the nineteenth century, it was deemed so disreputable that in Balzac’s 1846 novel Cousin Bette, a character discussing various eighteenth-century relics prefaces his mention of Les Liaisons Dangereuses with “if I dare say it.” (Even so, Balzac expected readers to know this forbidden book well enough to get the reference to another character as a “bourgeois Madame de Merteuil.”) Critics tended to dismiss the Laclos novel as vulgar, cynical and heartless. Still, it had major admirers, from Stendhal—whose own The Red and the Black, with its alternately Machiavellian and passionate protagonist, reflects clear influences from Les Liaisons Dangereuses—to Alfred de Musset and the Goncourt brothers. Beyond France, Byron channeled his fascination with Liaisons both into his work, with a romanticized Valmont reborn as the dark Byronic hero, and into his own tumultuous life (which sometimes resembled a more twisted version of the novel, complete with a Merteuil-ish confidante). In Russia, this fascination was shared by Alexander Pushkin, with motifs from Laclos appearing in the great verse novel Eugene Onegin (whose jaded hero’s belated awakening to love has a bittersweet and comical rather than tragic outcome) and other works.

The proper rediscovery of Les Liaisons Dangereuses began in the twentieth century, aided by cataclysms that swept away or greatly weakened sexual and religious taboos. To cultural radicals like André Gide, Laclos’s novel was a brilliantly subversive work imbued with a magnificently “demonic” quest for evil. Novelist and leading public intellectual André Malraux extolled it as an affirmation of hyper-lucid intelligence and eroticized will and credited it with pioneering an essentially new type of literary character whose behavior was motivated by ideas—a precursor, in that sense, of the heroes and antiheroes of Dostoyevsky’s novels, such as Raskolnikov. By midcentury, Les Liaisons Dangereuses was fully established as part of the “Great Books” canon; it also generated a wealth of scholarly literature examining it through every possible lens from psychoanalytic to mythopoetic.

In the late 1980s, the Hampton play and the Frears film—coming at a time when the novel’s themes of female empowerment, power struggles between the sexes, and the anxieties of sexual freedom had, perhaps, a particular relevancy—launched a new, international Laclos revival. Along with screen, stage, and musical versions, the surge of interest in the book inspired a string of novels. The earlier-mentioned A Factory of Cunning is one of several Merteuil-centric sequels and/or reinventions that also include the prize-winning Belgian novel Le Mauvais Genre (“The Bad Lot,” 2000) by the late Laurent de Graeve, an exquisitely written but sometimes heavy-handed brief for the marquise as a pansexual feminist ahead of her time. There are also the modern retellings whose range attests to the breadth of the original’s appeal, with the characters transplanted into a twenty-first-century French lyceum (We Are Cruel by Camille de Peretti, 2006), the black elite of 1950s Harlem (Unforgivable Love by Sophronia Scott, 2017), or the modern-day San Francisco gay community (Where the Vile Things Are by Marcus James, 2021). Even a #MeToo-themed tribute appeared last year: Cher Connard (“Dear Asshole,” more or less) by French novelist Virginie Despentes, in which a male writer “canceled” for past sexual sins engages a feminist actress in a cantankerous back-and-forth that evolves, in a reverse Valmont/Merteuil trajectory, into understanding and friendship.

Back to the Source

TODAY, AT LEAST IN THE ENGLISH-SPEAKING WORLD, most people’s familiarity with Les Liaisons Dangereuses comes from Frears’s Dangerous Liaisons, now a recognized cinema classic.

At the risk of heresy, I will say that despite some brilliant moments—including the opening sequence of his-and-her morning toilettes in which Valmont and Merteuil put on their battle armor—the film does not do the book justice. For one, the script alters or loses too many essentials, including the hints at genuine feeling between Valmont and Tourvel from the start. (Notably, the film’s Valmont goes to his aunt’s château with cold premeditation to seduce the renowned prude, while the book’s Valmont meets her there on a visit and is smitten with desire and maybe more.) The undercurrents of rivalry and hostility between the libertine duo are also missing, or at least drastically muted, until close to the end. The Prévan subplot disappears, and the marquise’s declaration of principles is situated in an affectionately intimate moment with Valmont rather than a moment of raw anger. Valmont’s breakup with Tourvel is carried out in person, with only a “beyond my control” cue from the marquise—which lacks both the horrific impersonality of the breakup letter and its literal scripting by Merteuil. Even the meaning of the catchphrase is altered: Here, it comes from Valmont’s offhand remark that his infatuation with Tourvel is “beyond [his] control” for the moment—precisely what the book’s Valmont strenuously denies.

There is also the film’s Valmont problem. Malkovich is a superb actor, but he so frequently makes the vicomte sleazy and/or scary instead of suave and charming that one may start wondering how this man finds willing women. (Miloš Forman’s 1989 Valmont errs in the opposite direction, making Colin Firth’s vicomte a charming rascal who, like the film itself, lacks the edge of malevolence or real danger.)

Some ten years ago, I was excited to learn that the playwright whose 1985 script for the stage sparked the now-decades-long vogue for Liasons, Christopher Hampton, was adapting Les Liaisons Dangereuses into a TV drama series—a format that, I thought, was much better suited to the novel’s complex canvas. Alas, this project eventually morphed into the STARZ Dangerous Liaisons series, a “prequel” giving our favorite scoundrels a ludicrous background of hardship and trauma. The future Merteuil, here known as Camille, is an orphaned housemaid-turned-prostitute who, through a series of strained plot devices, gets to pose as a child of provincial gentlefolk and then marry the Marquis de Merteuil. The young Valmont, meanwhile, has been robbed of fortune and title by a conniving stepmother and is using influential women as a pathway to upward mobility (shades of Guy de Maupassant’s Bel-Ami). Also, it eventually emerges that Camille/Merteuil is a rape survivor while Valmont literally watched his mother’s murder, an arc from Bel-Ami to Batman. Despite some good casting—Nicholas Denton’s Valmont could have been excellent in a script based on the actual book—it’s all as preposterous as it sounds, and worse. (Speaking of comic book scenarios: There’s a serial killer subplot.) The best thing about this misbegotten show is that STARZ reversed an early decision to greenlight a second season.

Les Liaisons Dangereuses is thus still waiting for the right screen adaptation. It is also overdue, by the way, for a new English translation: The last two, by Doug Parmée in 1995 and Helen Constantine in 2007, frequently misfire in aiming for a modern language (Valmont’s “infernal harpy” in reference to Volanges becomes “obnoxious old hag”; Merteuil’s “Redevenez donc aimable” to Valmont, best translated as “Just be likable again,” turns to “Be nice to me again”), and both misread some important passages. The 1961 P.W.K. Stone version remains the best if occasionally clunky option.

Even so: Read the book. “Timeless and timely” is a cliché, but sometimes it happens to be true. Feminist debates aside, the novel’s conflicts between solipsism and human connection, sexual agency and the need for love, echo and anticipate today’s conversations about sexual freedom; its world of endless socializing and fear of social “ruin” evokes today’s social media and “cancel culture”; and its rarely equaled ability to create characters who are “problematic” yet riveting, hateful and sympathetic, goes to the heart of the modern war over art and morality. Les Liaisons Dangereuses, which triumphantly survived more than a century of censorship and suppression, tells us that in this war, the right side of history is the one where great art is.