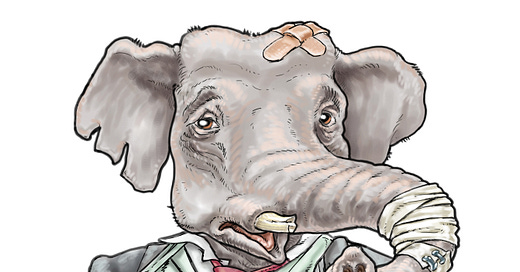

McCain-Feingold Gave Us Trump. It’s Giving Us Bernie, Too.

How the 2002 campaign-finance law left the political parties susceptible to hostile takeover.

When the history of this political era is written, major themes will include the unexpected rise of populism and Trumpian nationalism on the right and the rejuvenated fondness for socialism on the left.

The story of how we got to this point will be a rich and complicated one, involving widespread institutional decline, the unhealthy influence of social media, and so many other trends that made it possible for some of the worst of the worst to manipulate American politics—often while lining their own pockets. All of which was made possible by the Bipartisan Campaign Finance Act of 2002, better known as McCain-Feingold. While much has been written and debated about the late Arizona and former Wisconsin senators’ legacy legislation in the decade since the Citizens United Supreme Court case struck down parts of the law, far less has been said about how the parts not overturned by the Court—particularly its ban on soft money contributions to political parties—have done immense damage to American politics.

This shift of power away from the political parties resulting from this ban has led to the rise of outside groups and activists with narrow agendas, little incentive to compromise their views, and an eagerness to make themselves players in primaries. While some observers might cheer on this weakening of the elites, it has had the effect of turning the national political parties into glorified public relations shops for the White House when their party has the presidency. At the same time, the party out of power looks not just directionless but held hostage by fear of its own voters to appease small but vocal segments of their base—as seen in the rise of the alt-right in 2016 and the socialist hardcore Bernie supporters of 2020.

All of this was warned of years ago, as in this 2014 Washington Post op-ed by two election lawyers. After detailing the drop in fundraising by the two parties—a drop that meant a significant decline in the parties’ spending power—the authors explain that “it was the shortfall in fundraising relative to outside groups that most profoundly undercut the parties’ traditional role in our political system”:

Reliable figures on the total amount outside groups raised for election activity are nearly impossible to obtain because much of that activity is carried out through tax-exempt social welfare organizations and trade associations that are not required to disclose what they spend. Nevertheless, one way to gauge the growing spending advantage that outside groups enjoy over political parties is to look at broadcast advertisements, whose sponsors are required to identify themselves.

According to political scientist Michael Franz, since McCain-Feingold, the number of advertisements that political parties sponsor relative to other groups has fallen precipitously. In pre-reform 2000, the Republican and Democratic parties aired two-thirds of all advertisements in the presidential general election. In post- / reform 2004, that figure dropped to one-third; in 2008, it was less than one-fourth. By 2012, just 6 percent of all advertisements were sponsored by the political parties.

As a consequence, both the Republican and Democratic national committees have atrophied to the point that they are no longer able to exercise some core functions. Both national parties used soft money to support an extensive grass-roots network through their state party committees. As those funds dried up, the state parties shriveled. This hollowing-out has left the parties barely able to engage aggressively with outside groups on the left or right. With the parties hollowed out, proper candidate vetting fell apart. Republicans were first to be affected by this after George W. Bush left office. Free from any reprisal from the increasingly toothless Republican National Committee, the National Republican Congressional Committee, or the National Republican Senatorial Committee, or the ideologically friendly White House, outside organizations like the Club for Growth and former South Carolina Senator Jim DeMint’s Senate Conservatives Fund wreaked havoc in primaries across the nation. Instead of helping Republicans in winnable Senate seats, they often ensured Democratic successes by securing primary victories for heavily flawed candidates. Or they’d challenge an incumbent, who would still defeat their preferred candidate but be left beaten, blooded, and bankrupt.

All of which seems like a test run for 2016, when these and similar groups stuck to the sidelines as the RNC was helpless (or too scared of a third party run) to stop Donald Trump’s hijacking of the party and the conservative movement—a hijacking fueled by the very discontent with “conservative elites” these groups created.

As for the Democrats, their fracturing looks to have only been postponed by the Obama presidency. Like Republicans under Bush, the coalition’s cohesion was maintained when their party held the White House. But underneath the “Hope and Change” was a simmering discontent, a worry about “losing everything” to Republicans in the 2010 midterms. This fear birthed the left’s own purity groups—like “Justice Democrats” and the “Working Families Party,” whose muscle wasn’t truly flexed until the 2018 primary victory of New York Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (AOC). The far left, too, showed that it was capable of knocking off its own congressional leadership.

Much has been said recently about how 2020 is a repeat of 2016, particularly about how an outsider with no true ties to a political party has essentially taken it over. With Bernie Sanders’s early victories this presidential primary season, it looks as if there is little chance that Democrats will be able to stop him from being their nominee.

So with both parties shells of their former selves, the McCain-Feingold law will have helped pave the way for a nationalist and (possibly) a socialist to win the White House. Not exactly a legacy to be proud of.