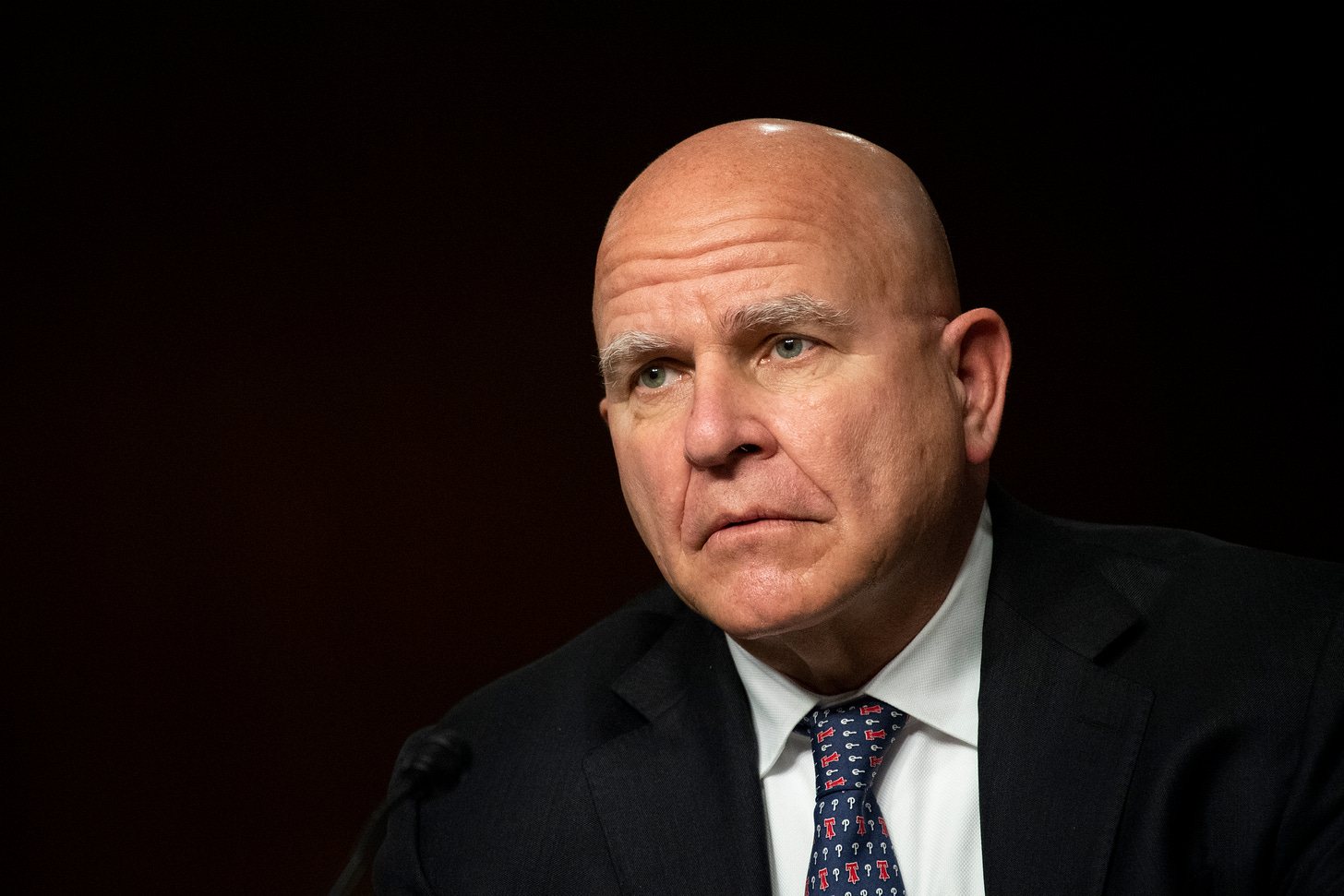

H.R. McMaster Can’t Save Himself From Trump

The general’s defense of the former president’s foreign policy shows this “adult in the room” has never quite managed to escape the room.

LT. GEN. H.R. MCMASTER HAS a good reputation. He’s a West Pointer and holds a doctorate in history from the University of North Carolina. His first book, Dereliction of Duty, based on his dissertation, was a bestseller and is considered a major contribution to the military history of the Vietnam War. His second book, Battlegrounds, garnered generally positive reviews.

As an officer, he is celebrated for his performance in the Gulf War Battle of 73 Easting, the last major tank battle of the twentieth century. During his tenure as national security advisor to Donald Trump, he was considered one of the “adults in the room,” and he received praise for directing the 2017 National Security Strategy and for generally keeping the wheels on the bus.

All of which raises the question: What the hell is he doing?

In a recent essay in the Atlantic, adapted from his new book, At War With Ourselves: My Tour of Duty in the Trump White House, McMaster argues that “Trump’s instincts in foreign policy were often correct.” But a careful reading of McMaster’s nearly 4,000-word article reveals that Trump’s instincts were often misaligned with his administration’s official policy, and McMaster can ascribe few if any accomplishments to the former president’s knee-jerk approach to managing America’s relations with the world.

Something else must be going on here.

McMaster asserts that he intends to give special focus to the “issues” where he thinks Trump had a “correct” hunch. But why does he consider it more important to review what he thinks Trump was right about than what he thinks his old boss was wrong about? Surely Trump’s failures are relevant to the merits of his current campaign for the presidency. But if that question ever occurred to McMaster, he didn’t address it.

Perhaps that’s because of how McMaster perceives “his job.” His role, he explains, “was not to supplant the president’s judgment but to inform it and to advance his policies.” Of course, that isn’t his role now, but he doesn’t comment on what he imagines his current one to be.

“Understanding how Trump’s personality and experiences shaped his worldview was essential to my job,” McMaster explains, using that pesky past tense again. As with many of the “adults in the room,” he was required to constantly reposition decisions, guidance, and basic information on the unsure basis of Trump’s capricious personality—a situation that, with its combination of indignity and insecurity, likely extracted a significant personal toll from him.

Being Trump’s national security advisor must not have been easy for such a serious guy. Imagine coming in to work every day and having to explain to the man in charge of the nation’s nuclear arsenal that No, we can’t just take Seoul and push it somewhere else. One hopes for the sake of his mental health that McMaster can recognize it is no longer his responsibility to do such things.

MCMASTER WRITES AS IF burnishing Trump’s reputation will in turn burnish his own. So, in the spirit of Grigory Potemkin, he conducts a tour of Trump’s “long-overdue correctives to a number of unwise policies.”

He opens at a high level: “In his first year, Trump articulated a fundamental shift in national-security strategy and new policies toward the adversarial regimes of China, Russia, North Korea, Iran, Venezuela, and Cuba.” This is a reference to the 2017 National Security Strategy, which McMaster himself principally authored. He did edit it to more closely suit Trump’s views, but ultimately the former president deserves credit for allowing McMaster to do a good job, nothing more.

“Trump repaired frayed relationships among Israel and its key Muslim-majority neighbors, and at the same time pursued normalization of relations between them, something that many observers had dismissed as a futile endeavor,” McMaster continues. But here again is almost certainly an inflated credit to Trump. The Abraham Accords were a triumph, but the rapprochement between Israel and its Arab neighbors has more to do with the involved parties than with Trump himself.

From this point in McMaster’s recap, the “successes” become even more hollow. Most of them seem to confuse activity with results.

For instance, he writes that Trump “unveiled long-term strategies to defeat the Taliban, the Islamic State, al-Qaeda, and other terrorist organizations,” which we might ask current representatives of the Taliban, the Islamic State, Al Qaeda, and other terrorist organizations to weigh in on, seeing as they not only still exist but directly benefited from the Afghanistan surrender agreement the Trump administration signed in Doha in 2020.

McMaster says that Trump’s hawkish stance on China—grounded in his belief that the United States must let go of its “strategy of soft-headed cosmopolitanism and hopeful engagement” in favor of “a policy based on clear-eyed competition”—was too chaotically applied to yield results, as the former president “swung between the use of enforcement mechanisms (investment screening, tariffs, export controls) and the pursuit of a ‘BIG deal,’ in the form of a major trade agreement with Beijing.” This is sufficient to prompt McMaster to make a rare admission that “Trump vacillated.”

But nowhere is McMaster’s reputation-polishing more obvious and more pathetic than in his retelling of a 2017 NATO meeting:

During the trip, I suggested to Trump that he press hard to get member states to increase defense spending while not giving Putin what he eagerly sought—a divided alliance. In the end, in his public remarks to alliance members, Trump made the points he wanted to make about burden-sharing without bringing up topics that would create cracks in the alliance.

Thus the colossus rides from victory to victory: the spirit of history on a golf cart.

There are more such achievements. “Trump,” says McMaster, “has a legitimate argument” about burden-sharing in NATO. He “saw China’s exploitation of the ‘free-trade system’ as a threat to American prosperity.” So Trump receives laurels for his firm grasp of the obvious.

McMaster devotes an outsized amount of attention to Iran, and here again we see a valorization of plans, stances, announcements, and intentions: “Trump . . . stated many times. . . .” “He was making the important point. . . .” “President Trump was eager. . . .” “Trump delivered a major speech. . . .” Nowhere does McMaster even try to point to meaningful outcomes resulting from all that jabber. It’s hard not to read these as the reflections of someone who still sees himself as the adult in the room accounting for what the child in the room did while under his care.

McMaster devotes scant attention to Russia and Ukraine, perhaps because he has already announced his focus on Trump’s successes, and that part of Trump’s record is where they are hardest to find. To start, he claims that “Trump imposed tremendous costs on the Kremlin for its initial invasion of Ukraine, in 2014.” This is highly misleading. Early in Trump’s term, Congress passed the Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act, which required the administration to impose sanctions; it slow-walked their implementation. And the bill’s impetus in the first place was not Russia’s 2014 invasion of Ukraine—which happened three years before Trump took office—but its interference in the 2016 presidential election.

McMaster should know that, because his own immediate predecessor was caught lying about promising the Kremlin sanctions relief and forced to resign before pleading guilty to lying to federal investigators and eventually being pardoned. This is how McMaster ended up in the Trump White House to begin with.

Curiously, McMaster barely touches on Trump’s foreign policy after he resigned—er, sorry, requested “a date for the transition to my successor”—in 2018, further confusing the issue of whether McMaster’s real subject is Trump’s record or his own.

MCMASTER’S FREQUENT CONFUSION OF the Trump administration’s policy statements with Trump’s actual activity might be related to his other blind spot about that time period. He generally avoids mentioning that under Trump, the formal interbranch and interagency process McMaster ran for 413 days was often at cross purposes with Trump’s personal foreign policy.

Official policy was to more heavily arm Ukraine. McMaster admits almost as an aside that Trump withheld “that assistance to seek an advantage over Joe Biden in the 2020 presidential election—in effect using weapons as a hostage, to be released when Ukraine agreed to try to dig up dirt on the president’s son and Biden himself.” One would think the national security advisor would have a little more to say about senior members of the national security council and State Department blowing the whistle on a “drug deal” run outside the official channels of the American government—especially one in which his brother officers were scapegoated and forced out of the Army.

Official policy, including McMaster’s National Security Strategy, considered Russia a major threat. Trump’s policy was to invite Russian interference in American elections, leak classified information from our allies to senior Russian officials, exclude American officials from his private meetings with Putin, exonerate Putin while denigrating the American intelligence community, espouse the supposed moral equivalency of the Russian and American governments, and promise sanctions relief. McMaster mentions several of these episodes in passing, but never connects the dots.

Official policy on China was to prepare for long-term strategic competition while preventing China from forcefully absorbing Taiwan. Trump’s policy was to raise tariffs, encourage the genocide of the Uyghurs, praise Xi Jinping at every opportunity, alienate both of our major allies in northeast Asia at the same time, and defend China’s handling of the emergence of COVID-19 in Wuhan.

Officially, the United States and North Korea are still at war, though in a prolonged armistice, and while American policy toward the hermit kingdom has been disorganized for decades, everyone agreed that the Kim regime was no good. Trump’s policy was to legitimize the regime and elevate Kim by calling him a model leader with a “beautiful vision for his country.”

The list could go on. When McMaster writes that “Trump’s instincts in foreign policy were often correct,” which instincts exactly is he talking about?

IF MCMASTER WERE MERELY FALLING all over himself in a vain and shortsighted attempt to polish his reputation, that would be one thing. But there are hints that he has other objectives in mind.

McMaster’s essay is littered with unnecessary and tendentious asides that evoke his former boss’s siege mentality. When he decries the “22-month, $32 million special-counsel investigation led by Robert Mueller, which in the end failed to find that Trump or his campaign had conspired with Russia during the 2016 election,” he sounds like he is framing things in Trump’s terms rather than his own. It’s particularly strange to see this complaint come from a career officer: McMaster would know that by the standards of the Defense Department, 22 months is quick and $32 million is cheap (it would buy about three of the tanks McMaster commanded in Iraq). And by any standard, potential “coordination”—that’s what Mueller was appointed to investigate, not conspiracy—between a hostile foreign government and a successful presidential campaign is more than serious enough to merit the time and resources that were required for the investigation.

McMaster similarly complains that the Washington Post criticized Trump’s “confrontational, nationalist rhetoric.” With a remarkable lack of self-awareness, he also notes that Trump was “angry over false charges of collusion with Russia and the considerable bias against him in the mainstream media.”

He persistently criticizes the foreign policy of the Obama administration, yet refuses to see the parallels between Obama and Trump—especially the degree to which both substituted words for action and tended to withdraw the United States from active leadership in the world.

Ditto the Biden administration. “Many Americans,” McMaster claims, “may have realized [the] value” of Trump’s policies “only after the Biden-Harris administration reversed them.” He provides no examples, but note that he throws the vice president in there—the only example of this construction in the essay; no “Trump-Pence administration” here—to signal that whatever Harris’s foreign policy stances will be, he disagrees with them, too.

Reputation-burnishing is a storied and sometimes even noble tradition in Washington. Major foreign policymakers do us all a favor when they open up and tell us why they made the decisions they did. But McMaster’s selective memory and gratuitous partisanship suggest that he’s not looking back as much as ahead. It’s almost as if the reason he writes like he still has his old job is that he thinks he could get that job back.

Maybe he doesn’t know Trump as well as he thinks.