H.R. McMaster on Working for a President Totally Unfit for the Job

He depicts Donald Trump as a vainglorious, manipulable ignoramus.

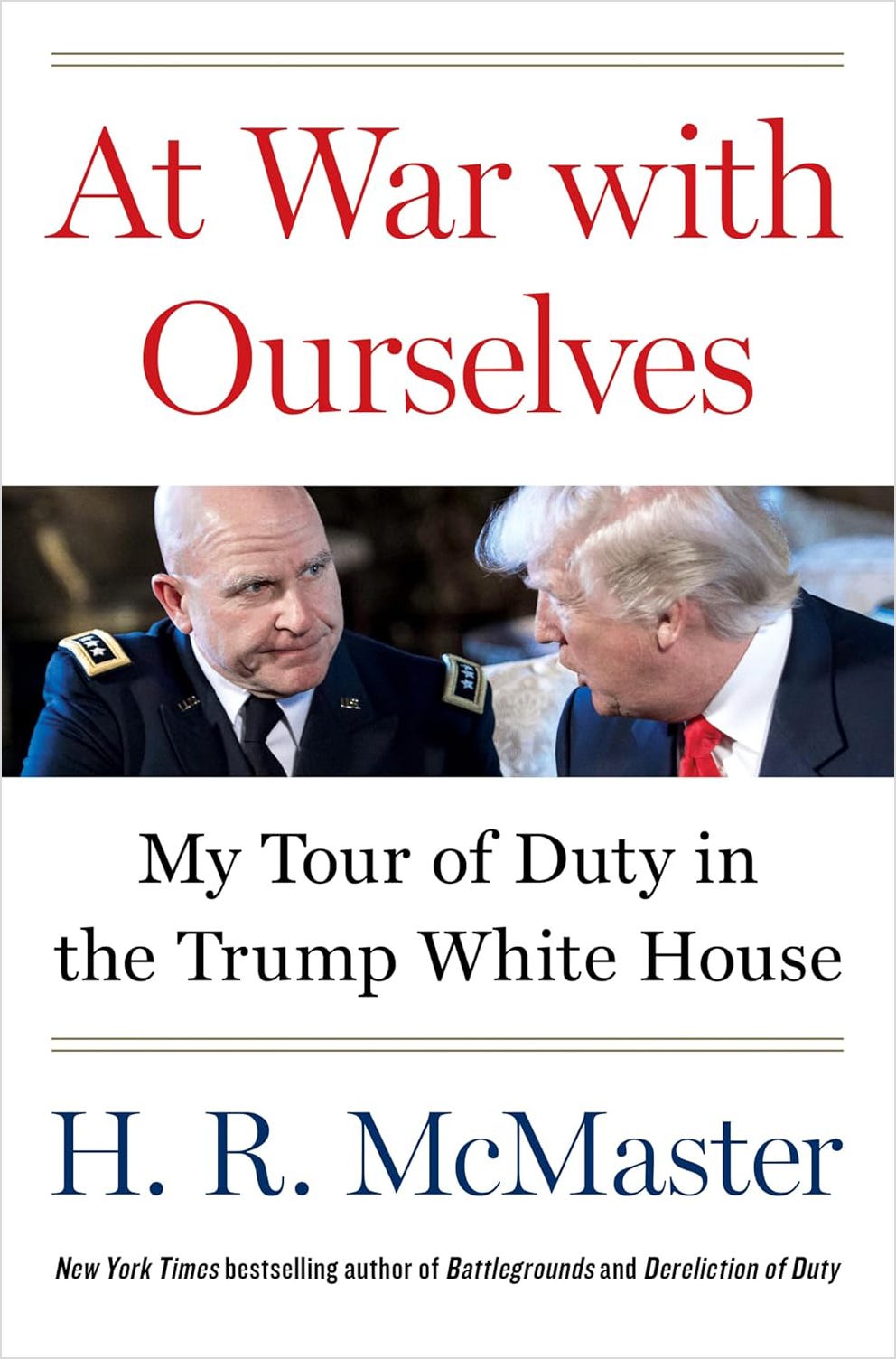

At War with Ourselves

My Tour of Duty in the Trump White House

by H.R. McMaster

Harper, $32.50, 357 pp.

CAN DONALD TRUMP BE TRUSTED once again with the reins of American foreign policy? The answer to this question is a resounding No. Trump is a grifter, an ignoramus, a skilled demagogue, a humorless clown, and manifestly unfit for public office at any level.

But if you had to make that case to an intelligent but uninformed visitor from, say, Jupiter, where would you begin?

One starting place might be At War With Ourselves, a new memoir by H.R. McMaster, who served as Trump’s national security advisor for thirteen months beginning in early 2017. McMaster is a graduate of West Point, a U.S. Army officer for thirty-four years who rose to the rank of lieutenant general, a decorated combat veteran, and the author of two previous bestselling books, including Dereliction of Duty, a probing analysis of America’s failed strategy in Vietnam.

His latest volume is a conventional day-to-day narrative of the making of U.S. foreign policy during his time working for Trump, with special emphasis on relations with Russia, China, the two Koreas, and the Middle East, as well as the war in Afghanistan. It is also a tale of his efforts from his White House perch to coordinate the Department of State, run by Rex Tillerson; the Pentagon, run by James Mattis; and fractious colleagues in the White House itself, including successive chiefs of staff, Reince Priebus and John Kelly; plus the alt-right firebrand Steve Bannon and the alt-right troll Stephen Miller. The picture McMaster paints, as his title suggests, is of serious dysfunction all around.

Both the State and Defense departments proved to be very difficult to manage. Indeed, Tillerson and Mattis joined forces to block McMaster at every turn and even to pressure him to quit. Trump, for his part, showed no interest in getting the machinery of government to work. Indeed, he reveled in the discord. As McMaster records, Trump was “always game for gossip, intrigue, and infighting, [and] often asked leading questions to see if I might criticize Tillerson or Mattis.” McMaster says he never bit.

To be sure, intense interbureaucratic friction is the normal condition of U.S. foreign-policy sausage-making. But this was something else. Tillerson and Mattis “seemed to have concluded that [the Trump presidency] was an emergency and that anyone abetting him was an adversary.” Accordingly, they “viewed my efforts as enabling a president who was a danger to the Constitution.”

One has to reach back to the last months of Richard Nixon’s presidency to find such fears about an American president being expressed by members of his cabinet. Remarkably, in the end McMaster concedes that Tillerson and Mattis may have been right: “Trump’s denial of the 2020 presidential election results and his encouragement of the January 6, 2021, assault on the Capitol Building might be invoked as an ex post facto justification for their behavior.”

As for McMaster’s relationship with Trump himself, the national security advisor makes it plain that the two men were not a good fit. McMaster writes of the “fundamental incompatibility of our personalities.” He notes that the “‘three As’, allies, authoritarians, and Afghanistan”—in short, the entire gamut of issues across the globe—“became millstones that ground down my relationship with Trump.”

Consider, for one example, McMaster’s difficulties in attempting to steer U.S. foreign policy regarding Vladimir Putin’s Russia. McMaster records complaining to his wife that “I cannot understand Putin’s hold on Trump.” In fact, as his memoir makes evident, he understood the hold perfectly well. Putin had skillfully zeroed in on Trump’s fragile ego, repeatedly buttering him up, with the Russian president describing him on one occasion as “a very outstanding person, talented, without any doubt.” Trump found such praise irresistible, replying “It is always a great honor to be so nicely complimented by a man so highly respected within his own country.”

Trump’s susceptibility to Putin’s flattery led to all sorts of otherwise inexplicable decisions, like his insistence on congratulating the “highly respected” Putin on his March 2018 re-election victory. “DO NOT CONGRATULATE” had been the words on his briefing card. McMaster recalls asking Trump: “As Russia tries to delegitimize our legitimate elections, why would you help him legitimize his illegitimate election?” He does not record Trump’s answer. Comments McMaster, Trump’s insecurity “made him vulnerable to tragic results.”

Or consider another of Trump’s peculiar qualities: his manipulability. In a draft of his first address to Congress McMaster found the phrase “radical Islamic terrorism.” He explained to Trump that it would be better to call it “Islamist” terrorism instead of “Islamic,” which focuses on the entire religion and fits the terrorists’ narrative of a clash of religions. Trump readily agreed to the change. But Bannon and Miller—eager to whip up fear of Muslims—got to Trump, who restored the word “Islamic.” Explains McMaster: the president “was prone to changing his mind based on whoever had his ear last.” A minor matter in the grand scheme of Trumpian failings, no doubt, but telling all the same.

Another personality tic: Trump was “reflexively contrarian.” One had to be scrupulously careful never to give direct advice as it almost always led to Trump doing the opposite of what was suggested. Thus, when Tillerson on one occasion advised the president not to say anything about military options for dealing with Venezuela, McMaster turned around and admonished him: “Rex, you know that he is a contrarian, and now the first thing he is going to say about Venezuela is that we are considering military options.” Sure enough, like clockwork Trump promptly told a reporter that a military option for dealing with Venezuela was on the table. It was for this reason, writes McMaster, that “I was careful not to tell him what I thought he should say.” This infantile pattern was repeated time and again.

Then there was the bizarre problem of Trump’s imaginary friends. A case in point: In contending with the ongoing war in Afghanistan, Trump would react to McMaster’s advice by saying that he had a “friend who is a real military expert” who had told him that a Taliban victory was inevitable because “Afghans are the toughest fighters.” Comments McMaster: Trump carried these defeatist nostrums around with him and “found it difficult to distinguish between those who brought him sound analysis and those, real or imagined, who brought him hackneyed bromides.”

Trump was also prone to willful incomprehension. In a speech being planned for NATO headquarters in Brussels, Trump insisted that if member nations did not “pay their dues” and “pay arrears” he would withdraw from the alliance. “I tried to explain,” writes McMaster, “as I had many times before—that the commitment was for NATO nations to spend at least the equivalent of 2 percent of GDP on their own defense capabilities” (emphasis added). In the NATO context, talk of dues and arrears was meaningless. Trump agreed to change the wording. But then, out of McMaster’s presence he changed it back and the nonsensical formulation was included once again. “Much worse,” comments McMaster, “he had added that the United States would not be obligated to come to the defense of countries that were ‘delinquent’ in their ‘payments.’” Only the last-minute intervention of Tillerson and Mattis persuaded Trump to take out the offending language. But hours later, he was at it again—criticizing countries for failing to “pay what they owe”—and his nonsensical talk of NATO “dues” and “arrears” was repeated many times throughout his presidency and beyond.

WHAT SHINES THROUGH THIS MEMOIR is the babysitting and handholding that McMaster—along with other “grownups”—had constantly to perform. As the national security analyst Daniel Drezner put it in the title of his own book, Trump was the “toddler in chief.” In a second term, should it come to pass, Trump has made it plain that there will be no grownups in the room. Political extremists like Bannon, Miller, and Gen. Michael Flynn, and assiduous sycophants like Kash Patel and Ric Grenell will be running the show.

McMaster strives to be balanced in his account, pointing to foreign policy successes along with failures, and even portraying some of Trump’s unusual character flaws in a favorable light. Trump, he writes, was often a disruptor of things that needed to be disrupted. Maybe so, in some few instances. But McMasters’s attempt to be evenhanded in assessing Trump nonetheless seems forced and unconvincing; it is the weakest part of his memoir. What emerges from its pages is a constant sense of dread and menace as a human freak—a creature wholly unsuited for the presidency, a man with no redeeming qualities, “the most flawed person I have ever met in my life,” in John Kelly’s words—grappled with the challenge of leading the world’s only superpower.

Trump, writes McMaster, suffered from “self-absorption, resistance to doing basic preparation, and a tendency toward disrespecting and disparaging those who were trying to serve him.” He had “a penchant for pitting people against one another.” He was “perpetually distracted” and this was coupled with a “loose relationship with the truth.” He was “distrustful and short-tempered, and inspired behavior in others that undermined teamwork.” His “longing for affirmation from his base sometimes sabotaged his wish to advance U.S. interests.” McMaster’s alarmed and alarming conclusion: “I couldn’t help but think that living at the base of an active volcano was an apt metaphor for serving in the Trump White House.”

With all of its danger, is this what we want again? McMaster has been catching flak for not telling the American people whom he will support in November. But really, that matters less than what he reports here. His book recounting what he saw of Donald Trump over thirteen months is a warning light flashing red.