Memorial Day: ‘Make It Matter’

A yearly ritual helps me reflect on the loss of my comrades and the meaning of their sacrifice.

THE FILM BEGINS WITH AN OLDER MAN walking through a peaceful cemetery. Keeping a few steps ahead of his family, he searches for someone’s grave marker. We see his intense concentration and feel his suppressed anxiety: He knows he is about to face something he has been carrying with him for decades. Finally, he reaches a white cross inscribed with the name he has been looking for. He collapses, overwhelmed.

With a jump-cut that takes us into his memories, the scene shifts to the hell that is war.

Helmeted men are packed into boats en route to a well-defended beach. Some are praying, others vomiting as the waves roll the hull. They’re all thinking of home, of loved ones, of danger, of mortality. As the door of the landing craft drops and the human cargo is dispensed, most of the men are unable to dodge the bullets waiting for them.

It is the most emotionally charged first 27 minutes of any movie ever made.

This opening is followed by scenes that evoke camaraderie, bravery, cowardice, leadership, and so many other virtues and foibles that soldiers experience in war. It is all part of the brilliant 1998 film Saving Private Ryan.

I watch it every year during the afternoon on Memorial Day. I usually like to be alone because I don’t like others to disrupt my thoughts or see my emotions.

The competing opening scenes of peace and terror are within a short walk of each other. The immaculately kept Normandy American Cemetery at Colleville-sur-Mer—where the old man walks at the beginning of the film, and where 9,388 soldiers, sailors, airmen, uniformed women, and war correspondents have been laid to rest since June 1944—is on a cliff. Down below, those landscapes of brutal violence, Omaha and Utah beaches, have become places of deep personal reflection amid the sound of lapping waves. These sites are sacred ground.

This year, many nonagenarian and a few centenarian veterans will commemorate the eightieth anniversary of the day of those landings—the “four score” remembrance of their generation. They will mourn the loss of those who didn’t come home with them and, even in their late years, they will still recall their comrades’ names.

And those they remember will remain forever young.

I THINK OF THESE REAL-LIFE VETERANS as I anticipate my Memorial Day ritual of reflecting on their fictionalized counterparts. The characters in Steven Spielberg’s movie—Private Jackson, the sniper; Technician Fourth Grade Wade, the medic; Private First Class Reiben, the smartass from Brooklyn; Private Caparzo, the burly soldier with the smile and the continuous wisecracks; Technical Sergeant Horvath; and, of course, Tom Hanks’s Captain John Miller—are fascinating to me, and even a bit eerie, for how they remind me of soldiers I have known and served alongside during multiple deployments. Only the names are different.

It’s been less than “one score” for me, and I still easily remember my soldiers’ faces, their unique personalities. Private Jonathan Falaniko, the young engineer who was the son of one of our command sergeant majors. Private Rey Cuervo, a Mexican immigrant who could be found studying for his citizenship test whenever he wasn’t on patrol. Specialist Michelle Witmer, a military policewoman, who was killed in a small arms attack. Second Lieutenant Lennie Cowherd III, who had been a friend to our son when they were at West Point together. Captain Rowdy Inman—also a West Point graduate—who was adored by his cavalry troopers. And, of course, Command Sergeant Major Eric Cooke, who was killed on Christmas Eve 2003 while patrolling with his men.

All of them would be much older today, had they returned home with us. When I watch the movie each year, I often replace the faces of Captain Miller’s small squad with those of the soldiers I served alongside. And after the movie ends, I go outside—alone, as the sun is beginning to set—to offer a bourbon toast to those men and women who will never grow old.

At the end of Saving Private Ryan, with his mission completed and his death drawing near, Captain Miller pulls Ryan close and whispers, “Earn this.” For my money, it’s the best line ever spoken—except one.

During one of my combat tours, when I was an assistant division commander to my friend and mentor General Marty Dempsey, he suggested at a soldier’s memorial service that we all should “make it matter.” He was calling us to consider the excruciating loss of each of our soldiers, and to commit to living a life worthy of everything they sacrificed.

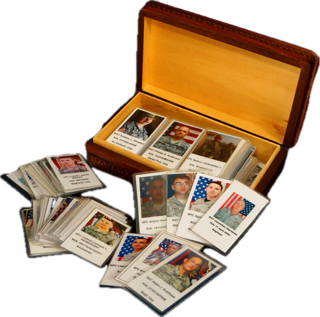

That expression—“Make it matter”—is engraved on a small wooden box I keep on my desk. The box contains 253 pictures of those who didn’t come home with us. Because I can’t walk through all the cemeteries across our country where those young soldiers now rest, I spend a bit of time looking through the pictures after I toast their memory. I wonder where they would be today if they had lived, what they would be doing, how their families might have grown.

And then, I think of what the much older James Francis Ryan says to his surprised wife at the end of Saving Private Ryan.

“Tell me I have led a good life,” Ryan whispers to her. “Tell me I’m a good man.”

During a time of divisions, of deep resentments and confusion in our country and across the world, I also want to know if I’m a good man—to know if I’ve lived a life worthy of the sacrifice of so many throughout our history.

We must earn it. We must make it matter. On this Memorial Day, and on every day of the year.