Mentally Seceding from the Union

It’s not just the combativeness of elections that drives Americans apart—it’s also how we live together and govern ourselves.

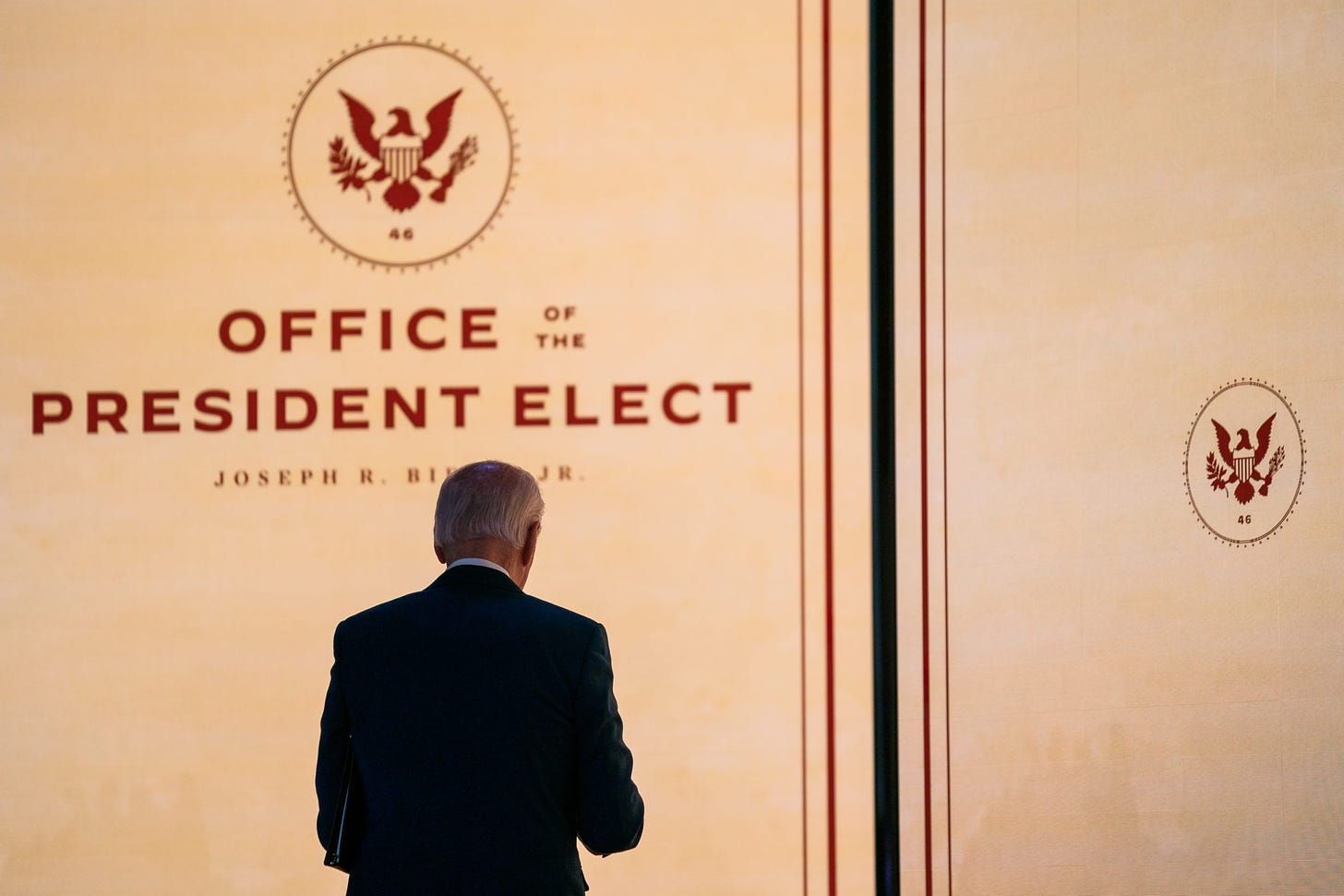

Having won the presidency of a deeply fractured nation, Joe Biden’s Thanksgiving Eve address was a call for reconciliation. “I believe this grim season of division and demonization is going to give way to a year of light and unity,” he said.

The season truly is grim. But to end it will require deep and sustained acts of statesmanship, to change how Americans see ourselves and our government.

When polls found seven in ten Republicans refusing to accept that Biden genuinely won the election, they were seen mainly as evidence of President Trump’s pre- and post-election efforts to delegitimize the election itself. But they also suggest a larger trend of delegitimizing election results. One in three Democrats disbelieved Trump’s own victory in 2016. Still earlier, George Bush’s and Barack Obama’s legitimacy was long challenged by small but vocal groups of partisans. Republicans’ dramatic levels of mistrust of the 2020 election results surely reflects Trump’s unprecedented months-long attack on the elections themselves, including his post-election statements and lawsuits; still, Republicans’ willingness to delegitimize this year’s election outcome builds on the skepticism of earlier years.

Elections take on a feel of civil war. Beforehand, strategists prepare with “war games,” conjuring up nightmare scenarios of their opponent’s misdeeds, and then preparing as if they were a certainty. Afterward, the losing side’s supporters seem increasingly comfortable with farfetched lawsuits—or worse—to delay or deny the results. Finally, when the reality of defeat becomes undeniable, the losing side styles itself as a “resistance” movement, while the winning side suddenly rediscovers its love of the American flag.

In October, Michael Gerson recognized that Trump was trying to talk Republicans into “mental secession.” If anything, he was too optimistic: The mental secessions had already occurred, among Republicans and Democrats alike. We live and govern ourselves less as a single nation than as two rival nations on contested lands. At any given moment, one nation is in power, while the other spends four years enduring it, resisting it, and looking forward to regime change.

Mental secession results from the way we live. We increasingly segregate ourselves geographically into communities of shared values, as Bill Bishop documented a decade ago in The Big Sort. And we segregate ourselves intellectually, relying heavily on politically or culturally inbred sources of information. No wonder a presidential election’s losing side sees the winners like foreign occupiers—the two sides live in different worlds.

Mental secession is worsened by the way we govern ourselves. Our Constitution originally entrusted lawmaking to Congress, so that our laws would be enacted through a checked-and-balanced process of deliberation and compromise, sometimes over the course of years or decades. Today, however, our government’s center of gravity is the administrative state, which makes law much more swiftly and unilaterally, and thus less moderately; groups not part of the president’s political coalition have no substantial voice in governance, except when they sue to block the agencies’ work.

Institutions that might dampen these problems are reinforcing them. Detachment from our federal government would be less significant if we channeled our energies into other attachments: state and local governments, charities, churches, or others. But today even our civic and private institutions serve often as components of the red and blue confederacies into which we’ve seceded—either proxies for, or tools to be wielded in, the national power struggle.

As Gerson noted, Abraham Lincoln came to office urging that “we must not be enemies.” But a quarter century earlier, he saw secession’s subtle source: “the alienation of [Americans’] affections” with each other and their government—that is, mental secession. Even if today we face no real risk of outright violence, it is good for President-elect Biden to decry “this grim season of division,” and to commit his presidency to healing those divides, before things get even worse.

But how? Many who decry “division” believe that the solution lies in “fixing” their opponents—changing what they can read, say, or think. That approach will only intensify mental secession. Instead, reunifying the nation will require extraordinary acts of statesmanship.

The president-elect already has taken the first step, striving often to address Republicans as fellow countrymen, not domestic enemies. But the next steps are harder. Once in office, he will need to pursue major policies primarily through legislative deliberation and compromise, not just administrative decrees, to show that governance is more than just the assertion of power.

Such an approach will not win over Biden’s most reflexive Republican opponents. And it will frustrate the most uncompromising members of his own party—especially after President Trump spent the last four years exemplifying the very opposite of statesmanship. Presidential candidates often say they want to be president of “all the people,” but the tools of the presidency and the demands of the party always pull in the other direction.

The next year will almost surely not be one of “light and unity.” But if Biden commits himself to it, he can bring us one year closer to rebuilding our government, and our union.