1. Two Stories

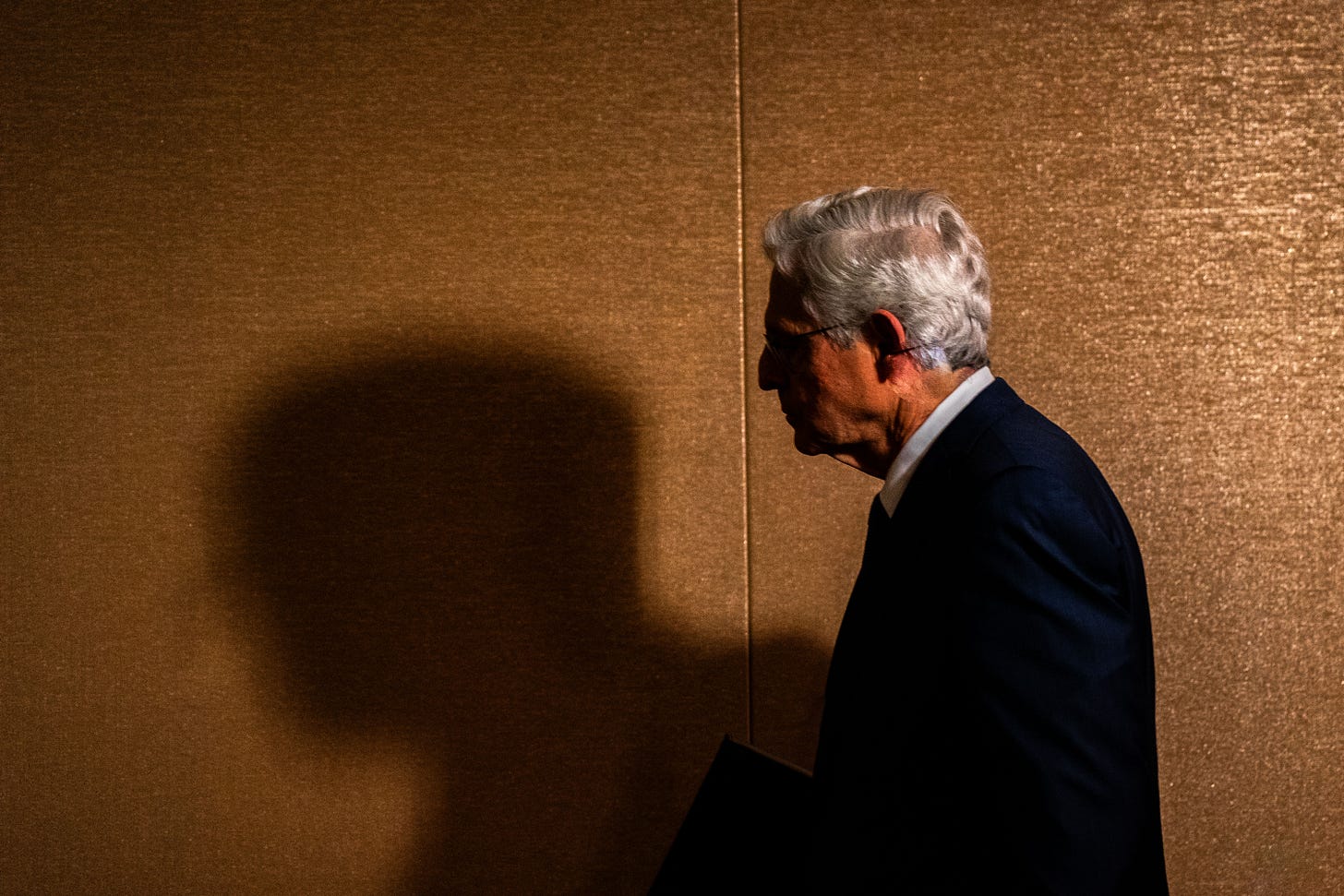

Was Merrick Garland’s tenure as attorney general a failure?

It certainly ended in failure. Garland’s DoJ prosecuted Donald Trump in two separate cases; neither was brought to fruition; Trump was then elected president. If one of the stated goals of the Department of Justice is to uphold the rule of law and one of the unstated goals is to prevent criminals from becoming the chief executor of the law, then yeah: Garland might be the worst attorney general in the history of the office.1

But I want us to look a little deeper, and doing so requires understanding the strategic environment Garland was operating in and the possible courses of action that were open to him.

Let’s start at 35,000 feet. It’s January 21, 2021. The former president has departed after attempting a coup. The new president is governing. If you are the attorney general and your overriding goal is defeating the next authoritarian attempt, there are three possible pathways:

Do nothing and hope the authoritarian movement in the Republican party burns itself out.

Engage the authoritarian movement cautiously and hope to isolate it from the main body of the Republican party.

Aggressively confront the authoritarian movement and hope to break its will to fight.

That’s it. Those are your options.

Garland chose Door #2. He gave Trump and Republicans space. He eventually engaged Trump somewhat reluctantly, but did so with the maximum amount of caution and probity. In the process he gave the Republican party—both the elected officials and their voters—every possible chance to abandon Trump. They didn’t take it.

From where we sit in January 2025 we know that it didn’t work. But was this obviously the wrong call in January 2021?

I don’t think so.

The story we tell about Garland today is:

Garland was too timid. By waiting to go after Trump aggressively he gave the authoritarian movement the ability to run out the clock, avoid accountability, and return to power. Garland should have come out of the chute at 200 mph and taken dead aim at Trump’s criminality from Day 1.

Declining to aggressively pursue legal accountability from the earliest possible moment is why Trump is our next president.

But we only tell that story because Trump won. For a minute, imagine that Garland had gone full-bore after Trump and Trump still won. Then the story we’d be telling ourselves today would be:

Garland’s aggressiveness turned Trump into a martyr and reignited the MAGA movement, forcing Republicans back into his arms. If Garland had been more cautious, the Republican party would have left Trump of its own accord and the authoritarian threat would have dissipated.

Aggressively pursuing legal accountability from the earliest possible moment is why Trump is out next president.

That’s the thing about analysis: You can’t let it be fully determined by outcomes. Sometimes you can make the wrong decision and everything works out. That doesn’t mean you made the right call.2

And sometimes you’re in the Kobayashi Maru, where you fail even after making the right decision.

Looking at the world as we understood it in 2021, I think Garland’s decision was risky, but reasonable. Had he decided to go hard at Trump from the bell, that would also have been risky, but reasonable. This was a judgment call, with huge stakes, and the decision was entirely on Garland. There was not committee, no vote. There was no one to share the burden of responsibility with him.

I don’t know about you, but I’m glad I wasn’t sitting in Garland’s chair. We ought to have some empathy for the guy.

2. And yet . . .

One of my favorite TV shows from the ’00s was House. The series was a retelling of Sherlock Holmes, only with Holmes as a doctor who solved medical mysteries. Hugh Laurie played the titular Dr. House and, like Sherlock Holmes, he was a bitchy, cantankerous wadbag.

In one episode, Dr. House is teaching a class of third-year medical students by presenting them with a hypothetical case about a farmer who says he’s been bitten by a snake and whose leg is going necrotic. House gives the class two treatment options and asks for a show of hands.

The exchange that follows has stayed with me for twenty years:

Student 1: I assume that one choice kills him and one saves him.

House: That’s usually the way it works at the leg-turning-black stage.

Student 2: So half of us killed him and half of us saved his life.

House: Yeah.

Student 3: But we can’t be blamed for—

House: I’m sure this goes against everything you’ve been taught, but right and wrong do exist. Just because you don’t know what the right answer is—maybe there’s even no way you could know what the right answer is—doesn’t make your answer right, or even okay. It’s much simpler than that. It’s just plain wrong.

That has to be our final verdict on Merrick Garland. Maybe we can’t blame him. Maybe there’s no way he could have known what the right answer would be. But his answer was wrong. It resulted in no convictions, a new Supreme Court writ of presidential immunity, and Trump’s return to power.

Garland was just plain wrong. And the rest of us will be paying for his mistake for a long time.

But I told you there was a lesson here.