Michigan May be a Nightmare for the GOP

The state party’s transformation didn’t start with Trump. But his weak polling could plunge MIGOP into wrack and ruin.

Simon & Garfunkel sang “Michigan seems like a dream to me now” as they went off to look for America. That lyric could well be running through the noggins of those in the Trump campaign and the Republican apparatus come fall, as they hope to reprise Trump’s shocking victory in the state in 2016.

A state that was on very few people’s radar in 2016 has become the center of the political universe this year, as our governor, Gretchen Whitmer, feuds with the president and as legions of political reporters travel to our state’s diners in an attempt to understand what they missed the last time around.

The problem with this renewed focus on Michigan? There’s not much evidence that the hype is real. As it stands today, Trump’s 2016 victory is looking more and more like a fluke, with every intervening election and the 2020 polls looking like a MAGA nightmare. The result is a situation where political campaigns and journalists are fighting the last war out of fear of being embarrassed again, rather than looking at the battlefield as it exists today.

If Donald Trump does win reelection, it is unlikely that his path will again run through my home state.

Let’s look at why that is.

For about as long as I’ve been practicing politics here—which is to say, since 1990—Michigan has tilted blue in presidential years. However, if you look at its voting patterns in the right light and from just the right angle, a brilliant shade of purple is revealed, marbled with red and blue hues.

After George H.W. Bush easily won Michigan in 1988, no other Republican even really tried. The younger Bush waged contested battles in the state as a diversionary tactic to distract Al Gore and John Kerry from neighboring Ohio. (Note: Bush garnered more total votes in 2004 while losing Michigan than Trump did when he won here in 2016.) Bill Clinton won big in both 1992 and 1996, Gore and Kerry both carried Michigan relatively comfortably, and Barack Obama did too, twice—even against native Michigander Mitt Romney, the son of a onetime governor, George Romney.

There is a bipolar aspect to Michigan’s voting patterns between presidential election years and gubernatorial ones. Beginning in the early 1960s with Gov. George Romney’s three consecutive election victories and counting through the turn of the century, Republicans held the governor’s mansion in Lansing in nine out of eleven elections. But in the five gubernatorial elections since 2000, Democrats have held a slight lead over the GOP: three wins to two.

Republicans have also controlled the state senate since 1984, after future three-term governor John Engler (1991-2003), then the minority leader, adroitly orchestrated the recall of two Democratic senators and voters then replaced them with Republicans in special elections. The Michigan Senate is elected entirely in non-presidential years. The Republicans’ iron grip on the chamber had grown to a veto-proof supermajority of 27-11 before the 2018 anti-Trump midterm cost the GOP five seats.

Republicans have held control of both houses of the Michigan legislature for 22 of the past 30 years—also having a GOP governor in 16 of those 22 years. (I played a significant role in the drawing of both the legislative and congressional maps adopted in 2001 and 2011.) But Michigan Republicans have had little success electing one of their own to the U.S. Senate, winning only one election (that of future energy secretary Spencer Abraham in 2000) since 1972.

Much of these off-year and localized GOP gains were offset following Trump’s victory in 2016. In the 2018 midterms, Democrats captured all the statewide offices for the first time since 1986, flipped two congressional seats, netted five seats in both chambers of the state legislature, and gained scores of county and local offices. Traditional GOP strongholds in suburban Detroit and Grand Rapids shifted to the Democrats. Gretchen Whitmer, a former state legislator, bested then-Attorney General Bill Schuette in a landslide, even winning Kent County (Grand Rapids), which had voted for a Democrat for governor just once since the founding of the Republican party in 1856. Rejection of Trump and Trumpism by Michigan voters in the 2018 midterm election left the Republicans at their lowest ebb in the state since 1986, though the GOP retained slim control of both chambers of the legislature.

Part of the reason that Michigan Republicans were able to have success in the past in this blue-leaning state is the ability to attract suburban swing voters with candidates known for personal decency and a willingness to cross the aisle. (It’s underappreciated on this count that Trump ran as an “Art of the Deal” heterodox Republican in 2016 and that, in some polls, voters reported perceiving him as more moderate than Hillary Clinton, something that wasn’t appreciated in the national media.)

Among the Michigan Republicans known for their crossover appeal, Gov. George Romney was vaulted to national front pages, like his son Mitt was last week, when in 1965 he walked with black civil rights protesters in Detroit. George Romney’s successor, Gov. Bill Milliken, U.S. Sen. Bob Griffin, and Congressman and National Republican Congressional Committee chairman Guy Vander Jagt had similarly deserved reputations for being tough politicians and gracious men. The Michigan Republican Party during this era was chaired by figures like Elly Peterson, the first woman in America to head a Republican state party organization, and Mel Larsen, whose name is part of Michigan’s Elliott-Larsen Civil Rights Act.

And the era of pragmatic Republican conservatism that John Engler ushered in dominated Michigan government and politics from about 1990 until the rise of the Tea Party.

The year 2010 was a foreboding one for Republicans in Michigan and nationally. It just wasn’t fully realized at the time. Running with the slogan “One Tough Nerd,” venture capitalist and former Gateway Computers CEO Rick Snyder emerged from a tough four-way primary against well-heeled establishment Republicans, including a retiring congressman, the state’s attorney general, and the elected sheriff of a county with a population of 1.2 million people. Snyder was the anti-politician, but quite different from Trump. Snyder was seen as civil, non-partisan, honest, and competent (and some would argue with more liquid capital than Trump).

Snyder’s ascent was concurrent with the rise of the Tea Party. Talk about apples and oranges. Like evangelicals two decades prior, many new activists appeared at GOP meetings across Michigan, ultimately making up significant portions of those chosen to be delegates at the Republican nominating convention that selected Snyder’s running mate and the nominees for attorney general and secretary of state. The Tea Partiers were feeling their oats and decided to flex their muscles by thwarting Snyder’s preferred choice for lieutenant governor, little-known two-term state representative Brian Calley.

The running-mate selection, typically a perfunctory voice vote by delegates at the convention to affirm the selection of the candidate for governor, was thrown into chaos when Calley’s nomination was loudly jeered by naysayers, who then moved for a tallied vote instead of acclamation. The party muckety-mucks behind the convention stage curtain shared a collective “Oh fuck” moment and then set about putting the genie back in the bottle. Threats were made, favors promised, pants shat, commitments exchanged, and ultimately deals were solidified and Calley was nominated. The Snyder-Calley ticket went on to a landslide victory in November.

The incident laid bare the divisions in the party that had been growing and lurking during Democrat Jennifer Granholm’s two terms (2003-2011). In 2012, racist homophobe Dave Agema defeated incumbent Saul Anuzis (now head of 60 Plus, the GOP’s counter to the AARP), for a coveted seat on the Republican National Committee. The MIGOP state committee, essentially a board of directors, became populated with miscreants and several actual convicted felons, including one who served time for extortion and conspiracy, another for financial fraud that included theft from his mother, still another mini-Bernie Madoff felon who was ordered to pay $285 million in restitution at his sentencing, and yet another, this one elected a party vice-chair, who had been convicted after shooting a man and also previously faced two counts of assault with intent to commit murder in a separate incident.

Tea Party gadfly Todd Courser went on in 2014 to win election to the Michigan House of Representatives where his service ended in less than a year: He was expelled following a bizarre sex scandal that gained national attention when Courser illegally used his staff to create rumors of his involvement with a male prostitute to distract from an affair he was having with a female GOP state representative. Courser was charged with four felonies, tried on two, and ultimately pleaded to a misdemeanor and lost his law license.

Not every up-and-coming figure in the state GOP was quite this bad, of course, but in the years after 2010, the state party came to be defined not by its sensible conservative moderation but by its unhinged populism and ethically challenged characters.

Polling through mid-2020 has shown Trump consistently trailing Joe Biden in the mitten state, including a survey released last week showing Trump trailing Biden by a 15-point margin (50 to 35 percent).

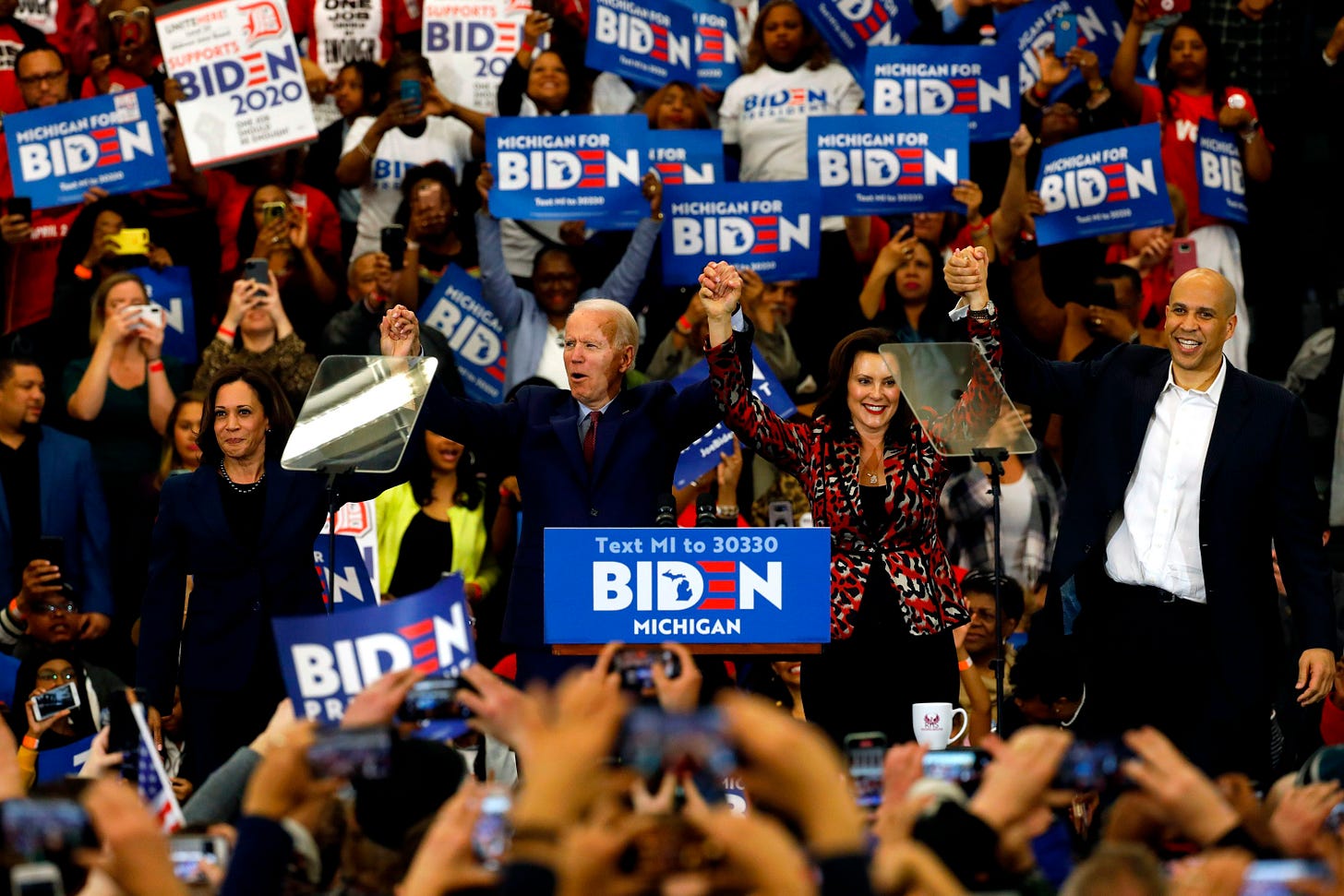

Democratic Gov. Gretchen Whitmer has only increased her popularity. Her approval numbers during the COVID-19 crisis, which has hit Michigan disproportionately hard, have remained in the mid-60s, while Trump’s have been mired in the low 40s. Whitmer gave her support to Biden at a pivotal moment in advance of his win over Bernie Sanders in Michigan and she is included in the speculation about Biden’s choice of a running mate. While Whitmer won’t be on the ballot in Michigan this year (unless Biden picks her), she’s in much better position to sway swing voters up and down the ballot than Trump or any Republican is.

These disastrous top-of-the-ticket numbers are sure to be an anchor for Republicans down-ballot—suggesting that the 2020 election will continue to hollow out the party in the state. For example, Republicans have an exemplary candidate challenging Democratic freshman U.S. Senator Gary Peters. John James, a black 39-year-old Iraq War veteran Army combat helicopter pilot, is the CEO of an international logistics company with annual revenue exceeding $100 million. James ran against three-term Sen. Debbie Stabenow in 2018, losing a surprisingly close race and running well ahead of the GOP’s gubernatorial candidate. James has tried to thread the needle of not alienating Trump and Trumpists while also endeavoring to not repel college-educated white voters who increasingly see Trump as less desirable than chlamydia. This needle is proving unthreadable: The most recent poll shows James trailing Peters 48 to 32 percent.

Freshman Democratic Reps. Elissa Slotkin (who defeated an incumbent Republican) and Haley Stevens (who flipped a GOP open seat) both face weak opponents and are likely to coast to re-election in their suburban Detroit districts.

In the southwest corner of Michigan, bordering South Bend, Indiana—where the Chicago TV market penetrates—moderate Republican Fred Upton, first elected in 1986, faces extinction at the hands of Democratic state representative Jon Hoadley. Upton eked out the narrowest victory of his career in 2018 against a relatively weak and little-known opponent.

Democrats also seem poised to break the GOP’s ten-year hold on the Michigan House of Representatives (state senators are not on the ballot this year) and either hold gains they made at the county and local levels in 2018 or add to them. Michigan adopted a new independent citizens’ commission to conduct redistricting after the 2020 census and the Democrats may well enter 2022 in their strongest political position since the mid-1980s to seize even more congressional seats and capture control of the Michigan Senate for the first time since 1984.

Most Republicans in Michigan seem oblivious to this reality.

What they have in front of them is the opportunity to do something pretty rare in politics, make a bold move that is both smart politically and the ethical thing to do. In this case: throw Donald Trump and his 35 percent ballot number overboard to try to save themselves.

There have been more than enough bright neon signs flashing out their warnings that a big blue wave has been forming. John James flashing 32 percent might as well be posted in Times Square.

But the message isn’t breaking through.

Instead, inexplicably, the MIGOP cult continues to bow and pray to the great orange god they made.

And so the sound most likely to emit from Republicans on the night of November 3, will not be silence—but a loud and collective wailing of defeat and despair.