Thursday Night Bulwark is coming! Put it down on your calendar. This week it’s Charlie Sykes, Amanda Carpenter, Sarah Longwell, and me.

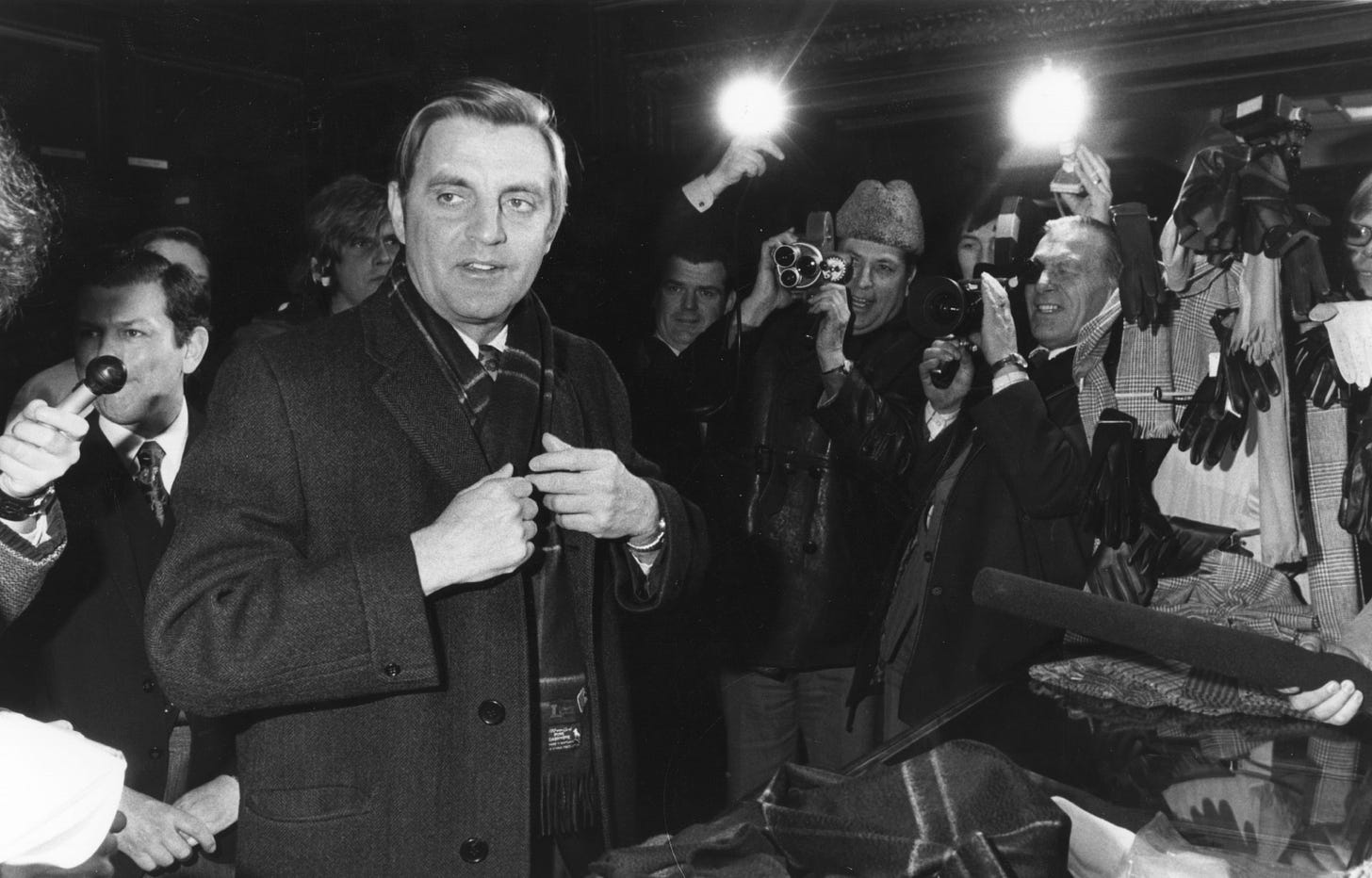

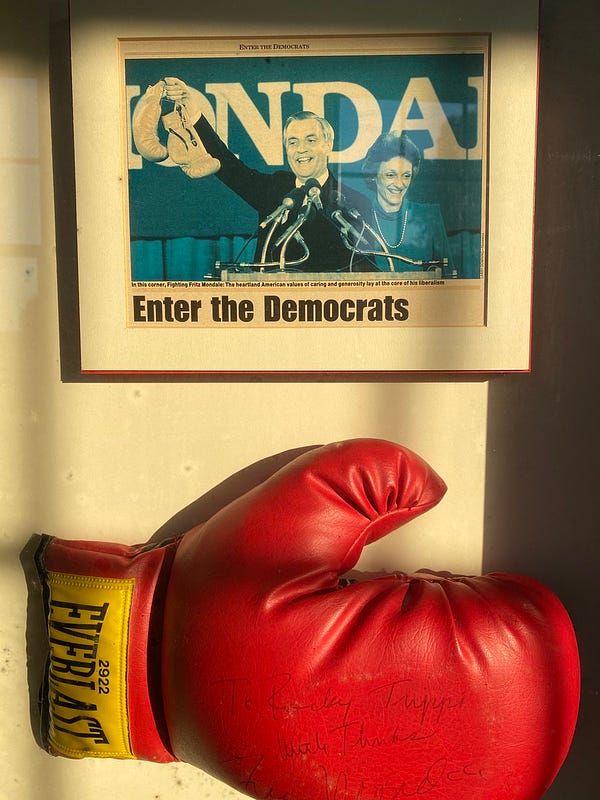

1. Walter Mondale, RIP

Walter Mondale was a punchline from my youth: The hapless Democrat, the big loser, part of a trifecta of liberals—Carter, Mondale, Dukakis—whose were notable mostly for their titanic ineffectuality, which forced the party to modernize and break with the liberalism of the ‘60s and ‘70s.

Mondale’s blowout loss suggested that the country was politically unified enough that landslides were possible at the national level. This turned out to be incorrect: 1984 was the penultimate landslide presidential victory. Barring some unforeseen development in society, we will not see its like again in our lifetimes.

All of which is to say that Mondale was never more than a caricature to me until I came to Washington and started reading about the politics of the ‘70s. Today, I mourn his passing because he was an example of a time when our politics was practiced by patriots.

I use this word in the original meaning, not in the current vogue as code for “anti-democratic nationalist.”

It’s funny to think, but Mondale came from a day where most national politicians had served in the military and not all of them—not even many of them—were products of the Ivy League.

His father was a minister. His mother a music teacher. He graduated from the University of Minnesota and then enlisted in the Army. He wasn’t a war hero or a super soldier: Just a normal middle-class American who served his country honorably for a couple years.

He went to law school and had politics in his blood. He organized for Triple H and local Democrats and had a talent for getting appointed: first as state attorney general and then to the U.S. senate.

He was an able politician. To wit: In 1972, Richard Nixon carried Minnesota with 52 percent of the vote—but Mondale held his seat with 57 percent of the vote.

Mondale was married to the same woman for nearly 60 years. He lost her in 2014—three years after losing his daughter, Eleanor, to cancer.

You can argue with Mondale’s policy preferences if you like. He was a liberal of his time and his politics are not my politics. They’re probably not your politics, either. It’s a different age.

But it is impossible to view his life as anything other than a beautiful, quintessentially American story.

Walter Mondale wasn’t a punchline. He was normal man trying to make America a better place. And he did so both in good faith and with genuine grace. May he rest in peace.

If you want to read the best story about Mondale ever, go and drink in this amazing thread from Joe Trippi. It’s the kind of thing that you never imagine happens outside of the movies.

2. Marco Kombat

At first I thought this was a Brutality, but it’s probably more like a Babality finisher. You have to watch it:

I don’t even know what to say.

The taxonomy of Trumpist Republicans is a pretty interesting branch of political science. Among the species in the ecosystem today you’ll find:

Sincere Trump acolytes

Faux Trump acolytes

Purely transactional Trump supporters

Anti-anti-Trumpists

Nihilists

Conspiracy theorists

Someday I’m going to do an entire taxonomic ranking for you. But I think Marco Rubio might be totally unique—an entire class of which he is the only member:

Republican who made specific warnings about Trump, all of which came true, but now supports Trump unconditionally anyway.

If Rubio was a normal human being and not a robot desperately chasing votes, he would have spent the last year telling anyone who would listen how smart he was and how he was the one who called everything about Trump exactly right from the start. You wouldn’t have been able to shut the guy up about it.

Instead, he still seems to think that there’s a place for him in national Republican politics—as if anyone in MAGA is ever going to view him as anything other than a tame globalist immigration squish.

The irony is that Rubio is a perfect example of the weakness of elite Republicans. And it’s that weakness which made Trump realize that he could take over the party and no one would raise a peep.

3. Norks

This New Yorker deep dive on North Korea’s cyber operations is across the board amazing. I cannot recommend it enough. Among the many interesting questions is investigates is how a country which actively works to keep 99 percent of the population off of the internet has been able to nurture a cadre of native-born elite hackers:

Few families own computers, and the state jealously guards Internet access.

The process by which North Korean hackers are spotted and trained appears to be similar to the way Olympians were once cultivated in the former Soviet bloc. Martyn Williams, a fellow at the Stimson Center think tank who studies North Korea, explained that, whereas conventional warfare requires the expensive and onerous development of weaponry, a hacking program needs only intelligent people. And North Korea, despite lacking many other resources, “is not short of human capital.”

The most promising students are encouraged to use computers at schools. Those who excel at mathematics are placed at specialized high schools. The best students can travel abroad, to compete in such events as the International Mathematical Olympiad. Many winners of the Fields Medal, the celebrated prize in mathematics, placed highly in the contest when they were teen-agers.

Students from North Korea often perform impressively at the I.M.O. (It is also the only country to have been disqualified for suspected cheating: the D.P.R.K. team was ejected twice from the competition, in 1991 and in 2010.) . . .

Two colleges in Pyongyang, Kim Chaek University of Technology and Kim Il Sung University, vacuum up the most talented teen-agers from the specialized math and computer high schools and then teach them advanced code. These institutions often outperform American and Chinese colleges in the International Collegiate Programming Contest—a festival of unsurpassed and joyful nerdery. At the 2019 I.C.P.C. finals, held in Porto, Portugal, Kim Chaek University placed eighth, ahead of Oxford, Cambridge, Harvard, and Stanford. . . .