Mitt Romney's Arc of History

For someone who has spent his life in the public sphere, Mitt Romney has an oddly ambivalent attitude toward history. “Frankly, I don’t think I will be viewed by history,” he told the Atlantic's McKay Coppins in an interview last year.

Lately, he's been thinking a lot about his father, George. The day before he marched with Black Lives Matter protesters, he posted a picture of his father marching for civil rights. His own decision to march felt like an homage to the senior Romney, who lost his own presidential bid in 1968. “My dad was an extraordinary man," he told Coppins, "but I don’t think history’s going to record George Romney’s impact on America . . . I don’t look at myself as being a historical figure.”

When he announced his vote to convict President Trump of abuse of power, he struck a similar stoic note: "We’re all footnotes, at best, in the annals of history."

But, he added, in a country like ours, "that is distinction enough for any citizen.”

His humility is hard-won. Historians may struggle to capture the political isolation of the former GOP nominee for president; despised for years by Democrats, rejected and exiled now by many of his former Republican colleagues. He joins a long list of men who came tantalizingly close to ultimate power, only to realize that fame is fleeting and obscurity is the default setting of the universe.

Being a presidential nominee is a very big deal, but who remembers John W. Davis (the Democratic nominee in 1924); or Alf Landon (the GOP sacrificial lamb in 1936)? Barry Goldwater (1964) and Wendell Willkie (1940) left deeper footprints, but they are the exceptions. I remember the week after the 1968 election, when my father pointed out that the name of Hubert Humphrey, the vice president of the United States, who had just lost the presidency, to Richard Nixon, was not even mentioned in the newspaper that day. Humphrey was a good and decent man, but when is the last time you heard his name mentioned?

So there's no reason to doubt Romney's skepticism about history.

And yet . . .

There comes a point in your life when you look back on where you came from and begin to think how you will be remembered. Romney appears to be at that point.

His vote to convict Trump—a president of his own party—felt like a legacy-defining moment at the time.

But Sunday represented something more.

His decision to march didn't just challenge Trump, it defied generations of conservative orthodoxy, indifference, and denial. Other than retiring Texas representative Will Hurd, he was the only Republican there.

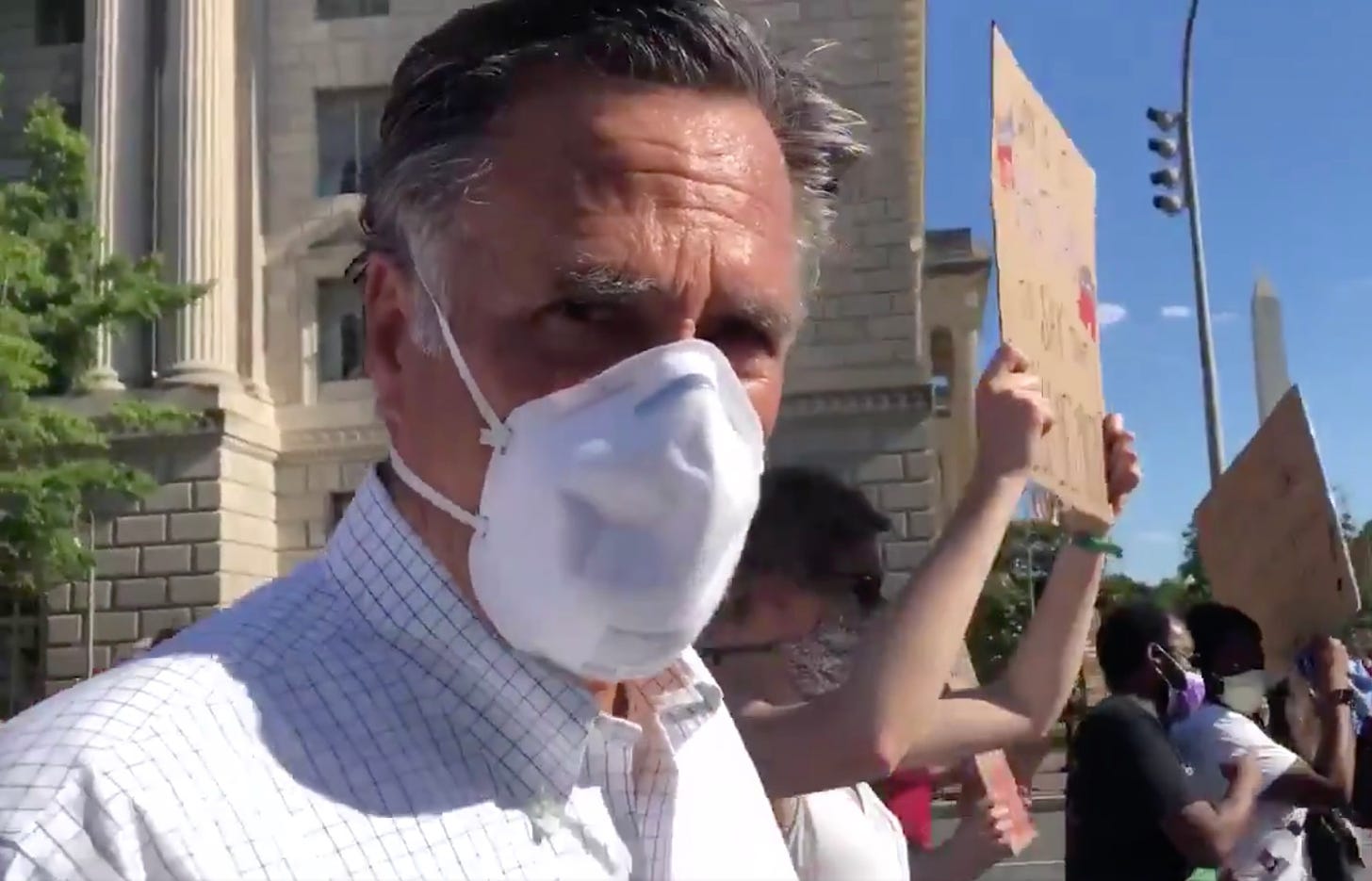

Asked why it was important for him to be present at the protest, Romney, who was wearing a face covering, said: "We need a voice against racism. We need many voices against racism and against brutality." . . . "We need to stand up and say black lives matter," added Romney, who was marching with a Christian group.

As Tim Alberta notes, it will require a lot more than "Mitt Romney marching with Black Lives Matter protesters in Washington or Steve King being cast off by the party in Iowa" to change the trajectory of the GOP.

But if the arc ever bends, Romney's march (along with George W. Bush's statement of support) may be remembered as an inflection point.

The incident also highlighted the contrasting visions of the party. Predictably, Trump felt compelled to lash out.

Contra Trump, Romney is quite popular in Utah.

Actually, Romney polls better in Utah than the president, and his approval rating has actually risen in the state.

Some 56% of Utahns support Romney, a freshman senator and the 2012 Republican presidential nominee, according to a poll earlier this month by UtahPolicy.com and KUTV. About 42% of Utah voters disapproved.

Trump, meanwhile, is only a few points ahead of the presumptive Democratic presidential nominee Joe Biden in Utah. An April poll showed 44% of Utahns would support Trump in the election while 41% said they’d back Biden in the deep red state.

A January poll by The Salt Lake Tribune/Hinckley Institute of Politics found most Utahns would probably or definitely not vote to reelect the president.

Romney also found himself getting some Strange New Respect:

For the record, this is not what Democrats have said about Romney in the past. Although it now seems several lifetimes ago, back in 2012, Democrats savaged Romney as everything from a charlatan to a felon, to a racist. Joe Biden himself famously said of the Romney-led GOP “They’re going to put y’all back in chains.”

At the height of the 2012 campaign, John Harris and Alex Burns noted that both sides had engaged in negative campaigning:

But there is a particular category of the 2012 race to the low road in which the two sides are not competing on equal terms: Obama and his top campaign aides have engaged far more frequently in character attacks and personal insults than the Romney campaign....

Obama, who first sprang to national attention with an appeal to civility, has made these kind of attacks central to his strategy. The argument, by implication from Obama and directly from his surrogates, is not merely that Romney is the wrong choice for president but that there is something fundamentally wrong with him.

To make the case, Obama and his aides have used an arsenal of techniques—personal ridicule, suggestions of ethical misdeeds and aspersions against Romney’s patriotism—that many voters and commentators claim to abhor, even as the tactics have regularly proved effective.

In the wake of Sunday's march, there were some attempts at revisionist history, but Alberta, wasn't having it.

https://twitter.com/TimAlberta/status/1269785019582746624

Romney, of course, had his share of gaffes and he was not blameless. He notoriously cozied up to Trump despite the fact that Trump was trafficking in birtherism.

All of that is now in the distant past, except that it reminds us how our politics can treat a fundamentally decent man and, perhaps, why it is ultimately so dangerous to accuse someone like Romney of racism . . . especially when the real thing finally comes along.