NATO’s 75th Anniversary Was a Missed Opportunity

The Washington Summit should have been about the alliance’s future rather than its past.

TWENTY-FIVE YEARS AGO, WASHINGTON HOSTED the 50th anniversary summit of NATO’s founding. It was a special event in many ways but most notably because it formalized the entry of Poland, the Czech Republic, and Hungary into the alliance. It also offered a process for which other countries in Central and Eastern Europe could prepare themselves for NATO membership—a historic achievement only ten years after the Berlin Wall had fallen.

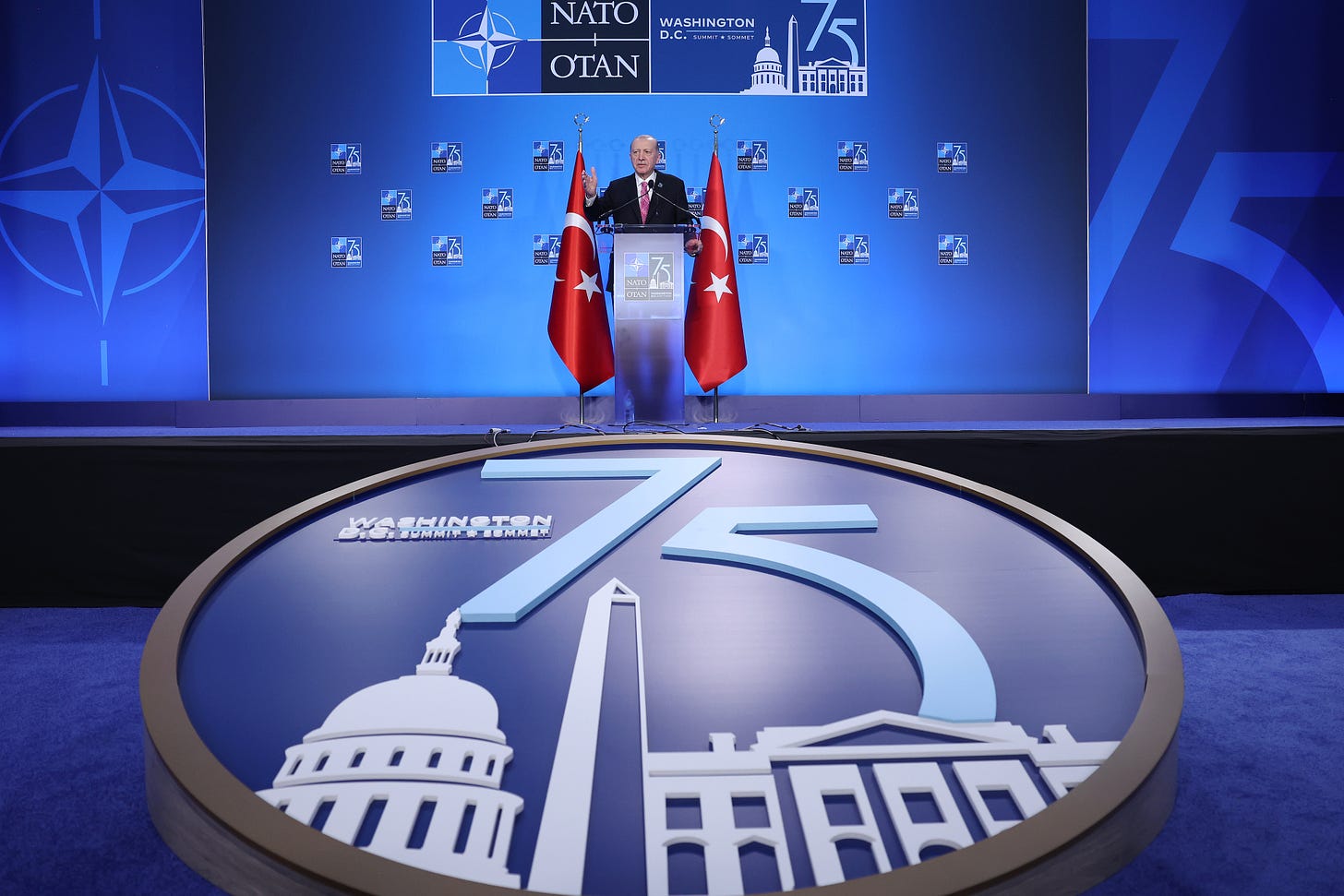

This past week, Washington hosted the NATO summit on the 75th anniversary of the signing of the North Atlantic Treaty. European and Canadian leaders joined their U.S. counterpart to honor the alliance’s achievements, issue statements of support for Ukraine in its struggle for survival against Russia, sign new defense production agreements, and make clear that China is on notice for its increasingly destabilizing actions around the globe and particularly supporting Russia against Ukraine.

It’s become standard after these annual summits for experts and commentators to proclaim them great diplomatic successes and decry their failure to meet expectations. That’s usually because both statements are accurate: NATO is the most successful military alliance in history, so any demonstration of its continuity into the future is a success. But for decades, the alliance arguably has been slow to meet its responsibilities and plagued by problems from unequal burden sharing to strategic listlessness to rogue members. This summit, too, had successes to celebrate as well as troubling failures.

In many ways, this year’s summit was a success in that it reaffirmed transatlantic solidarity, both in word and deed, for Ukraine’s war of self-defense against Europe’s greatest aggressor, Russia. The gathered leaders declared that nearly three-quarters of their countries were spending the agreed-upon minimum of two percent of GDP on defense. And all member states reaffirmed the importance of NATO’s Article V commitment—the organization’s most sacred foundational plank—that an attack on one is an attack on all.

If there were any doubt about where Congress stood on this issue, Senate Foreign Relations Committee Ranking Member Jim Risch put that to rest when he declared at NATO’s public forum that:

NATO was formed for the exact circumstance we find ourselves in today . . . Article V means exactly what it say—an attack on one is an attack on all. Not one square inch, whether it’s in the Baltics, whether it’s in London, or whether it’s in New York. Not one square inch. Mr. Putin, listen. Article V means exactly what it says. I make that commitment now for the United States. The United States is there to meet that commitment if we ever have to.

As far as the past and present are concerned, the summit was a success. But it failed to do what it most needed to do, which was to develop a vision for NATO’s next 25 years. For whatever reason—lack of imagination, having had too many summits in recent years with too many deliverables, or just lack of consensus—the summit focused much more on the alliance’s past than its future. At a moment when the world seems to be in chaos, the NATO leaders missed a critical opportunity to lay out a vision of how the alliance would address tomorrow’s threats.

The Summit could have been so much more. Leaders could have put a timetable on when Ukraine would join NATO—or at least explained what “conditions” would enable Ukraine to join. They could have made the decision to put trainers on the ground in Western Ukraine to support the Ukrainian military in its efforts to learn and adapt against Russia tactics. They could have made clear the alliance will do “whatever it takes”— not just “as long as it takes”—to help Ukraine win against Russia. Americans, at least, are supportive of these positions: A recent Reagan Institute survey found that 75 percent said it is important to the United States that Ukraine win the war, and 57 percent said we should continue to send weapons to Ukraine.

The argument against bolder action to help Ukraine is that it could be seen as “escalatory” and draw NATO members into a fight against Russia. But does that really seem likely? Hasn’t Putin done everything possible to avoid a direct confrontation with NATO, while simultaneously making clear his campaign of political warfare against the “collective West”? Hasn’t he demonstrated that he does not respect Ukraine’s right to exist, NATO’s decision to admit the nations of Central and Eastern Europe, and the West’s system of democracy and free markets? Haven’t he and his armies of cyber warriors already attacked Western governments and their infrastructure since the mid-2000s? Haven’t he and his intelligence agencies been actively trying to interfere in allied nations, including our own, elections since at least 2016?

There’s room between being a warmonger and being a naif. The West has failed to force Putin into a strategic dilemma that would force him to reconsider his foreign adventurism. Formally starting the process of bringing Ukraine into NATO could clarify the dictator’s thinking.

NATO leaders paid lip service to the campaign of “cognitive warfare”— disinformation and malinformation—against us by Russia, China, and other states and groups. As our foes are attacking our institutions, trying to divide our populations, and split the alliance, the leaders couldn’t do more than “reiterate that hybrid operations against Allies could reach the level of an armed attack and could lead the North Atlantic Council to invoke Article 5 of the Washington Treaty.” That’s not enough. Russia, China, et al. seek to exploit divisions within our nations and across our alliance on issues such as support to Ukraine, climate change, and migration. They seek to portray democracy as chaotic and globalization as unwieldy and disorienting. They want us to believe we are lost and focused on the wrong things. They want to have us retreat so that they can defeat us without having to directly engage us.

NATO and its members have tools to combat these efforts. For many reasons, democracies do not like to talk about how they counter mis- and disinformation efforts. This has to change. As democracies, we need to be able to recognize when we are being attacked but also what impact those attacks are having on our functioning institutions and societies. The summit was an opportunity to announce that the alliance was going to invest heavily in more capabilities and be proactive to counter Russia and China’s cognitive warfare efforts in Ukraine and across our populations.

In contrast with NATO, Russia and China do not have allies; they find commonality in their grievance against the West. They are collaborators. Democracies are even more loath to discuss using information warfare offensively than they are to discuss defending against it, but Russia and China have severe weaknesses, both structurally within their economies and personally amongst their leaders. The corruption in both countries should be leveraged. Cognitive warfare strategies and tools can be used against them with their populations—using only the truth. We do not have to announce exactly or specifically what the tools are; just stating publicly that we will be exponentially increasing our spending and abilities to counter Russia and Chinese efforts would change our enemies’ risk calculus.

Another, related area for improvement that the summit bypassed almost entirely is societal resilience. The summit declaration recognizes that “National and collective resilience are an essential basis for credible deterrence and defence and the effective fulfillment of the Alliance’s core tasks in a 360-degree approach” and follows that up with more buzzwords like “whole of government approach” and “public-private cooperation.” The real problem is that most people in NATO countries take security for granted. Because of NATO’s success, most Americans, Canadians, and Europeans have not had to think about putting on a uniform and defending their town, state, or country—let alone an ally. We have been able to prosper, innovate, and lead with a tiny minority of citizens actively defending our way of life. We have the freedom to be who we are and do what we do because we do not have to worry about going to war or being attacked.

As a result, we lack resiliency across our societies (Northern and Eastern Europe arguably excluded). We lack an understanding of sacrifice. Whole-of-society resilience is difficult to comprehend if war isn’t imminent—just ask the Ukrainians. NATO Article III is about resilience and requires member states to take the necessary steps to prepare its territory and populations for Article V situations. Nations must invest in the necessary infrastructure and other means to be able to not only respond to an Article V action but also to be able to receive allied support during such a time. Summit leaders should have spent more time addressing this issue, encouraging new initiatives to strengthen collective resilience and to visibly demonstrate that we will remain prepared and committed in the face of anti-democratic aggression.

The Berlin Wall has been down for almost as long as it was up. For some, arguments about NATO’s relevance and effectiveness have persisted since 1989. Yet, following Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, nations such as Sweden and Finland wanted to break from decades of neutrality to become NATO members. Ukraine, itself, wants to join NATO. Why is that? Of course there is the obvious answer: NATO is a military alliance which protects its members and has not been formally attacked by a nation-state since its existence. Countries want to be under the security blanket.

But NATO isn’t just a military alliance. It’s also a political alliance. Countries want to join and remain members because of the alliance’s shared values and principles. They want to be part of something that protects their way of life. They want the peace, security, and prosperity that being a NATO member brings. They are willing to sign up to the Article V commitment to ensure the dominoes do not fall.

In recent weeks, I have been able to be part of a groundbreaking initiative through the Center for Strategic and International Studies to bring Hollywood screenwriters to NATO and to have them listen and engage with leadership on what NATO is, stands for, and means. It has been inspiring to both watch how the world’s greatest storytellers have had their eyes opened as well as how they have been able to make “connections” as to what NATO means to so many people both within and outside of the alliance.

The connection perhaps could not have been more touching and revealing as when the screenwriters—by pure happenstance while visiting NATO headquarters—ran into a group of Ukrainian soldiers who had just returned from the Invictus Games in London. The soldiers were all wounded, some missing limbs, another an eye. All were in good spirits and wanted to chat with the screenwriters. As the storytellers departed after ten minutes of discussion, one of them paused, shook the hands of a soldier, and said, “Thank you for fighting for us!” Such a moment was impactful, honest, and resonant with regard to the war’s effects.

NATO’s future is up to the citizens of its member states. We have the power to tell positive, impactful stories about what NATO means to us and our way of life. We have the means to counter the efforts of Russia and China to not only distort our stories but also to take these stories away from us.

Let’s not squander this moment. No enemy can match or overwhelm the collective power of more than 1 billion like-minded citizens of the United States, Canada, and Europe—if we remain united in cause and deed. NATO’s first 75 years are a testament to unity. Let’s make sure the next 25 years are even stronger than the last. To do this, our leaders need to make brave, bold, and future-oriented decisions, just as their predecessors did in 1949.